Twenty years ago last month, I opened the New York Times and saw the face I knew so well and the headline, “Carolyn Heilbrun, Pioneering Feminist Scholar, Dies at 77.” Sound mind, sound body, yet she’d taken her own life, leaving only the words, “The journey is over. Love to all.”

Shock waves rippled through our little corner of the world. She was, as Sandra Gilbert called her, “the feminist-critical mother of us all.” She was the first woman to get tenure in the Columbia English department, author of groundbreaking books on women writers and feminist criticism and the mystery novels she published under the pseudonym Amanda Cross. She was a role model, inspiration, and a friend.

Shock waves rippled out into a larger world as well, for her words had touched many. The year she retired, 1992, a celebration was held at the CUNY Graduate Center, “Out of the Academy and Into the World With Carolyn Heilbrun.” “Into the world” her words had traveled, for her writing was that rare thing, scholarly yet readable, an inspiration to women of all kinds. When she came out as the author of the Amanda Cross mysteries, she became a kind of cult figure. Then in 2003, nearly as many gathered for her memorial as for the celebration, as Nancy Miller recalls, noting that anger at her suicide ran through the reminiscences “like a dark thread.”

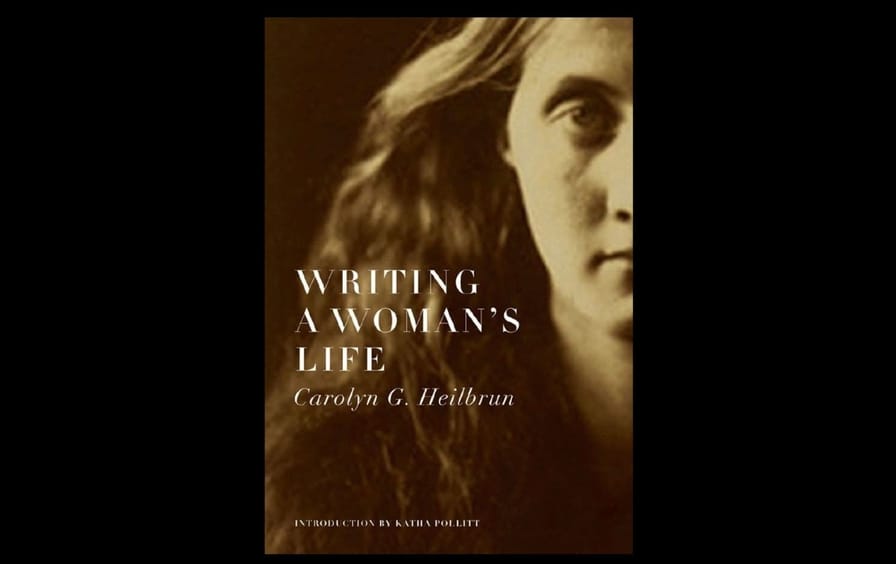

We told ourselves stories, the kind one tells about suicide, how we must grant people their lives, their deaths, even if we don’t understand. “She crafted her own plot,” we said, “made her narrative her own”—and how like Carolyn that was, whose theme in her book Writing a Woman’s Life was that women should be authors and directors of their lives.

I was a graduate student at Columbia in the late 1960s and early ’70s, years when she taught there. I’d been advised against taking a course from her by one of the male faculty who made the chilly climate she exposed in Death in a Tenured Position and other Amanda Cross mysteries, so I didn’t get to know her until later, at conferences where we became friends. In the early ’90s, I invited her to be part of a collection of essays I was coediting with Coppelia Kahn. We were asking women scholars to reflect upon the processes that had transformed their literary scholarship to feminist scholarship, that had enabled them to connect the personal and political and use feminism in their writing and teaching. Carolyn, by this time, had been elected president of the Modern Language Association, and even Columbia had to honor her, giving her an endowed chair in 1986. She wrote a generous afterword to the anthology I coedited, Changing Subjects: The Making of Feminist Criticism, and ever after we met for dinner when I was in New York. Always we’d meet one-on-one, neither of us much caring what we ate as long as there was quiet and plenty of wine. Hungry only for conversation, we’d hunker down—what are you reading? What are you writing? Those dinners were precious to me, and too few. She was wonderful company, had a wicked sense of humor. I could have talked with her forever.

Only now, decades later, do I dare take The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty down from the shelf. It is painful to reread because she says such hopeful things about growing older, and that it was the friendships she’d made with younger feminists that “after a lifetime of solitude and few close and constant companions…helped to make my sixties my happiest decade.” She describes women writers as guides to other women, opening up possibilities: “women catch courage from the women whose lives and writings they read; and women call the bearer of that courage friend.” Of the poet May Sarton, she writes, her “wisdom was, for me as for many, a support and a promise offered by someone who had been there before and could explain the journey.”

Did she not realize that she represented these possibilities to us? She’d written of suicide, never ruled it out, describing it as “leaving the party while it’s still fun.” Could she not see that leaving like that might do a wrecking job on the party?

A lot of us, not knowing what to think, put her out of mind. But for too long, I’ve let her death define her. Today, I remember her in full, the friend, the scholar, the guiding light. Second-wave feminism has been faulted every which way, but it’s well to remember its many gifts. As Carolyn writes, “today’s women students—unlike my generation…know that there are books waiting for them, as there were no books for me…know that others have been there, have recorded their experience, know that help is available.”

A proud legacy, thanks to Carolyn Heilbrun and other women who wrote those books. She may have bruised our hopes, but she also raised them up high.