When Jodi M. Savage was in her sophomore year at Barnard College, she found herself in a terrible depression. Sensing that something was amiss, her grandmother, who had been caring for her since bringing her home from the hospital eighteen years earlier, took the long cab ride from Brooklyn out to her granddaughter’s dormitory and sat beside the bed all day as the young woman cried. An evangelical Christian, her grandmother spent the hours praying and “writing in the spirit” — which is to say, putting a kind of glossolalia down on notebook pages — until night fell.

“We never spoke about why I was sad,” Savage writes.

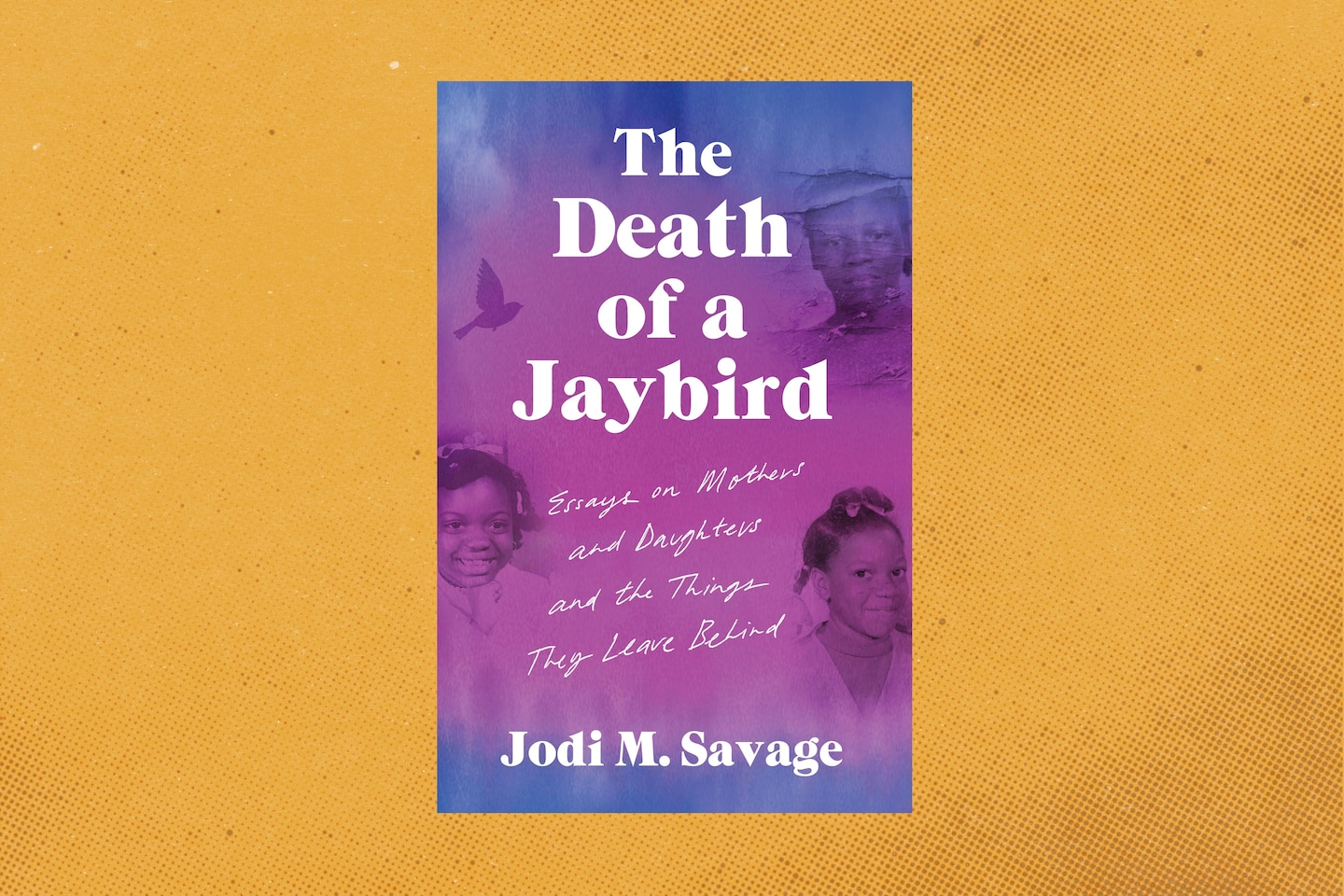

Appearing late in Savage’s beautiful debut, “The Death of a Jaybird: Essays on Mothers and Daughters and the Things They Leave Behind,” this anecdote is both a tribute to the steadfast love her grandmother showered on her over the course of her life, and a gentle, but firm, critique. For Savage, who is now approaching middle age, her grandmother’s faith and its effects were “my curse and her legacy.” Through eleven connected essays, beginning with the last months of caretaking for her grandmother and ending with snippets from her funeral, the book explores the labyrinthine nature of grief. It takes regular stops along the way, traversing the continued vicissitudes of life that invariably endure within the event horizon of loss and mourning.

Savage, who has worked as an attorney in addition to being a writer, writes that she feels dissociated from the religious institutions around which her early life revolved. She is embittered by the misogyny of male pastors, not to mention the shame that religious dogma induced in her when it came to her sexuality and self-expression. But she has also at times, like her grandmother, felt held by the church. Indeed, she gives a final goodbye to her grandmother in part by placing a pink suede Bible into her hands.

Born in 1937, Annie Lee McKinney — Savage’s grandmother — left segregated Florida for New York City on her own in the 1950s to work as a live-in domestic. Church was a place for her to find Black community; its other members became “her surrogate family.” In grieving for her grandmother, who died in 2011 from complications related to Alzheimer’s, which included at times psychotic features, Savage also feels like she needs to parse through her associations with religion, not to mention her interactions with police officers and the various medical professionals involved in the final days of her grandmother’s life. She is grateful for her grandmother’s relatively peaceful passing, but cognizant, too, of how easily things could have gone differently, perhaps even violently.

Over the course of the book, she also takes up her relationship with her mother, from whom she was sometimes estranged and who struggled with mental illness as well as drug addiction. In the years following her grandmother’s death, Savage’s mother, Cheryl, was diagnosed with breast cancer, as Savage herself would be soon after. These events repeatedly reconfigured their relationship, in addition to recasting the grief she felt over her grandmother’s death. When her mother dies from the disease in 2021, Savage once again enacts, through her winding essays, the ways that various losses shape and reshape one another.

Interwoven between explorations into these intimate topics are detours brought together in essays probing yet loose, with the steady pulse of a continued grief always ready to emerge. Savage leaves razor-sharp insights on almost every page, and wields a well-honed mix of earnestness and humor, the latter exemplified by a few of the lists that pepper the volume (“How to Attend a Black Funeral”; “What Not to Give Someone Who Has Breast Cancer”). She regularly revisits moments from the past to identify and trace shifts in her own perspective. This stylistic approach is reminiscent of Joan Didion’s cyclical writing pattern in her grief memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking.” But unlike Didion, Savage, who opts for a collection built out of individual essays rather than a single unspooling storyline, looks beyond the obvious spaces in which her grief unfolds. She includes regular meditations on less recognizably related topics, like her decision not to have children; her relationship to various friends and strangers who have widened her own sense of community; and the often-harmful treatment she and her grandmother have received as Black women in various medical settings. Through it all, she also digs into her family history, full of surprises that compel her to continually reevaluate the primary relationships of her life — her “two mothers” — however different her connection to each.

As Savage makes clear throughout, there is no way to separate either love or grief from the conditions that shape them. “This is the nature of Black grief,” she writes, in a chapter that moves from diaristic entries about her mother’s final year to snippets of watching the trial following George Floyd’s murder in that same time, which unseals for her additional floods of sorrow. “Our personal and collective losses combined and compounded. Our daily lives are a reminder that your loss is my loss is our loss.”

Savage’s dexterous interventions into experiences of Black life and loss join a growing pile of works by authors creatively reimagining the relationship between grief and writing, including Elizabeth Alexander, Lorene Cary, Edwidge Danticat, Natasha Trethewey and Jesmyn Ward. In addition to detailing the variegated textures of grief, Savage grapples with the complicated relationship between telling and not telling. Though she never had the opportunity to describe all her sadnesses to her grandmother, it was her grandmother’s model — her love of the written and spoken word, and her unremitting support — that brought Savage to the book in which she finally unburdens herself. “Writing was how she communicated with God,” she explains. “Like Granny, I feel closest to God when I am writing.”

Tahneer Oksman is an associate professor at Marymount Manhattan College, where she teaches courses in writing, literature and cultural journalism.

The Death of a Jaybird

Essays on Mothers and Daughters and the Things They Leave Behind

By Jodi M. Savage

Harper Perennial. 227 pp. $18.99, paperback