In the early summer of 2022, I flew into Lincoln, Neb., picked up my rental car and drove into a Willa Cather novel. Stretched out before me was an expanse of farmland alternating with tall, undulating grass. Once in a while, an isolated house would appear in the distance and a truck would rumble by, heading in the opposite direction on the two-lane road. After the prolonged Zoom-box confinement of the pandemic, driving for hours through such an expanse made me giddy. Here’s how Cather, who lived for decades in New York City, described returning home to Red Cloud, Neb., in a 1933 letter to fellow writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher:

“The certainty of countless miles of empty country and open sky and wind and night on every side of me. It’s the happiest feeling I ever have. And when I am most enjoying the lovely things the world is full of, it’s then I am most homesick for just that emptiness and that untainted air.”

The occasion for my own trip into that glorious space was the annual Willa Cather Conference, held that year in Red Cloud. I gave a talk about Cather’s 1922 novel, “One of Ours” — set, as so many of her novels are, on the prairie, but extraordinary for its vivid depiction of the 1918 flu pandemic and World War I. Ernest Hemingway, whose contempt was always a reliable marker of how threatened he felt by the gifts of another writer, quipped in a letter to critic Edmund Wilson that the war had been “Catherized” and suggested, falsely, that she’d lifted her battle scenes from D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation.” How peeved Hemingway must have been when “One of Ours” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1923.

And how very exasperated Hemingway would be by this “Year of Cather” that’s now drawing to a close.

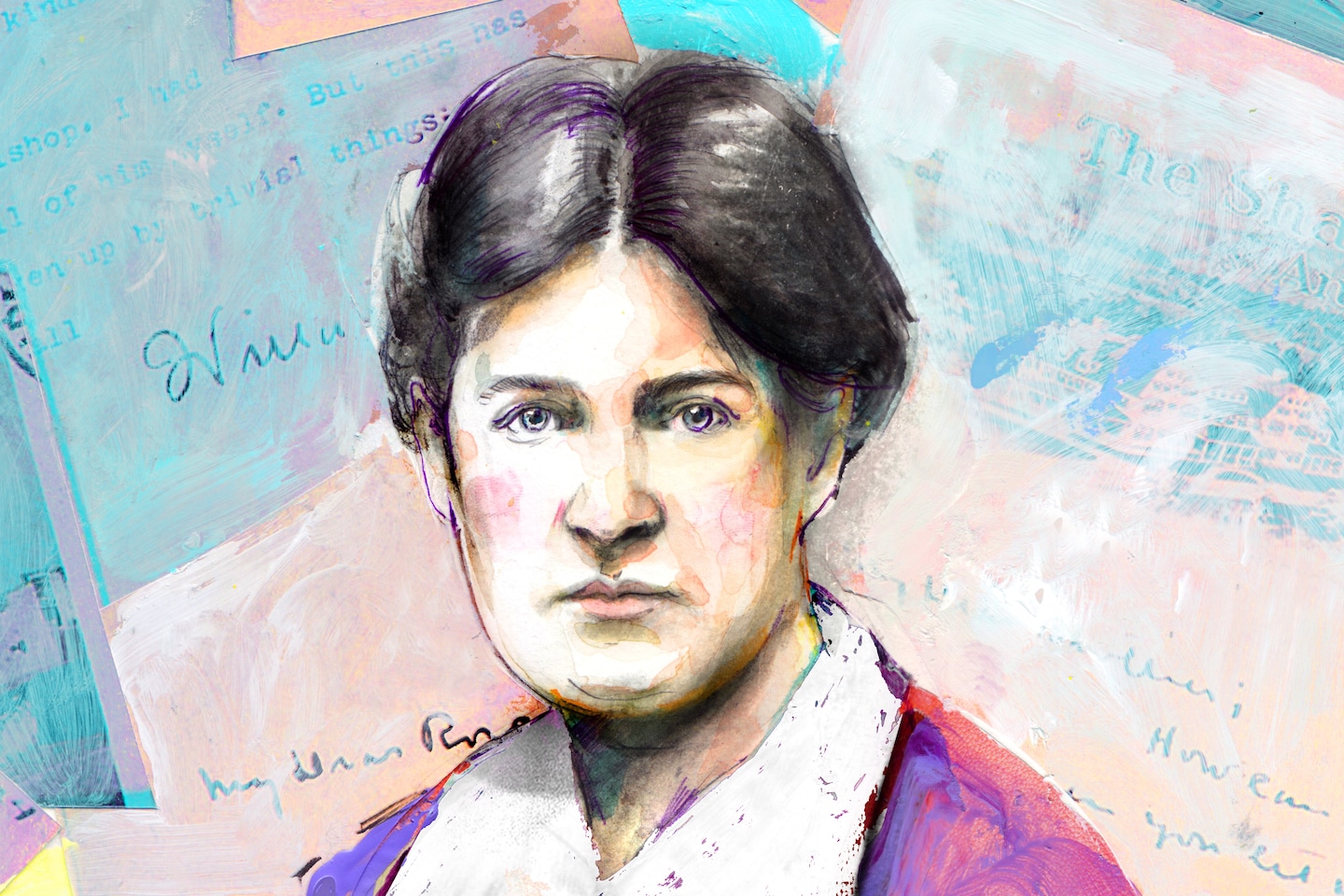

To mark a flurry of Cather anniversaries in 2023 — the 100th anniversary of that Pulitzer Prize; the sesquicentennial of her birth near Winchester, Va.; and the publication centenary of one of her most haunting novels, “A Lost Lady” (as well as the reprinting of the 1903 poetry collection “April Twilights, and Other Poems”) — celebrations and staged readings of Cather’s work have been going on around the country. In June, Cather’s preeminence as an American writer was made manifest in bronze when her sculpture was unveiled in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol. Holding a walking stick in one hand, a notebook in the other, Cather scans the Nebraska landscape she immortalized in her novels, among them “O Pioneers!” (1913), “The Song of the Lark” (1915), “My Ántonia” (1918), “A Lost Lady” (1923) and “The Professor’s House” (1925).

Benjamin Taylor’s slender, discerning new biography, “Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather,” might also be numbered among these tributes. Cather, of course, has long attracted the attention of some superb long-form biographers and critics, tops among them Hermione Lee and Joan Acocella. Apart from the cluster of Cather anniversaries, the spur for this new biography was the expiration in 2011 of the legal strictures against quoting from Cather’s letters. Famously insistent that her work, not her life, should be the focus of critical attention, Cather set up a trust in her will to enforce that ban after her death in 1947. Years before, in one of those awful incendiary moments that flare up in literary history, Cather burned the letters she’d written to the great love of her life, Isabelle McClung. Earlier biographers were restrained to paraphrasing Cather’s letters, often resulting in AI-like approximations of her arresting voice and descriptions of nature. Taylor, happily, had full access to Cather’s “Selected Letters,” published in 2013, as well as to the 2,700 or so letters that have been digitized in the ever-growing Willa Cather Archive at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Taylor says in his prologue that his biography “arises from a debt of love” to Cather for her writing. It’s a graceful, old-fashioned gesture of a statement that signals the tone of this biography, which is designed for, to borrow Virginia Woolf’s term, “the common reader.” But “Chasing Bright Medusas” should appeal to anyone — novice or expert — ready to explore Cather’s life and work in the company of a critic so alert to the shimmering subtlety of her style and the hard years of effort that went into crystallizing it.

Taylor’s most recent book, “Here We Are,” was a memoir of his friendship with Philip Roth — another American literary genius whose hometown (in Roth’s case, Newark) was the gift that kept giving. Here, Taylor summons up Red Cloud, where Cather’s family moved in 1882 when she was 9. At that time, the town and surrounding prairie and farmland were populated by immigrants from Scandinavia and Central Europe, as well as quiet eccentrics like the English clerk William Ducker, who read Virgil and Ovid in the evenings with the young Cather. This swirl of immigrant friends and neighbors instilled in her, as Cather once put it, “a feeling of an older world across the sea.” Doubtless it helped form what Taylor sees as Cather’s bedrock anti-modernism. Contrasting her to her younger contemporaries — Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald and Dos Passos — whom he characterizes as “men who wrote mockingly about the illusoriness and deceptiveness of ideals,” Taylor says: “What makes her the greatest of anti-modernists is that ideals were what was most real to her.” (I object to sweeping Fitzgerald into this cynical crowd. After all, “The Great Gatsby,” which Cather read and told Fitzgerald she enjoyed, tells the story of a doomed dreamer who yearns to repeat the past.)

She left Red Cloud at age 16 for the University of Nebraska. Taylor evocatively says that “she believed in luck, particularly her own, and believed in the luck-making power of desire.” As a girl, Cather clearly had the power to inspire others with her vision: Her father borrowed money for her tuition, and before that, her parents carved out a makeshift room of one’s own for their eldest daughter in the attic dormitory she shared with her six brothers and sisters.

During college, Cather began a decade-long career of practicing what we would call “cultural journalism,” churning out the kind of reviews that earned her the appellation “meat-ax girl” from an early editor at the Nebraska State Journal. She held writing, editing and teaching jobs in Pittsburgh until she received a life-giving invitation in 1906 from McClure’s Magazine to move to New York and become an editor and contributor. Still, Cather was driven by grander ambitions for her writing. Taylor quotes a 1913 letter she wrote to her friend Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant in which she laments: “If only I could nail up the front door and live in a mess, I could simply become a fountain pen and have done with it — a conduit for ink to run through.” Perhaps, in addition to housekeeping, what Cather yearned to be “done with” was sexuality.

Taylor is an especially nuanced commentator on the vexed “Was she or wasn’t she?” question of Cather’s sexuality. The bald biographical facts read as follows: Cather as a girl was unconventional (wearing boy’s clothing, chopping off her hair and experimenting with male signatures like “William Cather Jr.”). In college, she had a fierce friendship with a fellow intellectual named Louise Pound, which generated the single letter in Cather’s vast archive that speaks at all to the issue of her sexual identity. “It is manifestly unfair,” Cather wrote to Pound in 1892, “that ‘feminine friendships’ should be unnatural.” In 1899, Cather met Isabelle McClung. The two women shared a bedroom at McClung’s parents’ house in Pittsburgh for five years. McClung eventually married, a devastating event for Cather, who went on to meet Edith Lewis, the editor with whom she lived from 1908 till her death.

“Probably” is a qualifier the scrupulous Taylor frequently resorts to when dealing with subjects he feels are resistant to a biographer’s scrutiny. So it is that he deploys “probably” when considering the question of Cather’s sexual identity in that Louise Pound letter: “The letter is a profession of love. … Is it consciously lesbian? The answer, though not easy, is probably no. … Rather than speaking of one kind of love, the letter prefers to talk about love at its most exalted, above the reach of mere carnality. Willa saw herself as exceptional rather than homosexual. But that she was homosexual is obvious, astounded though she would have been to know it.”

This is a quick two-step of a paragraph, but rather than being evasive (which, doubtless, some readers will take it as being), it seems to me a rigorous effort to fathom how Cather understood herself. Throughout his discussions of Cather’s novels, Taylor underscores his steady insight that, for her characters, “sex is … the worm in the apple.” To name but one instance of many, Marian Forrester, the luminous heroine of “A Lost Lady,” fades into the novel’s “lost lady” because of her humiliating erotic liaisons. Similarly, marriages are mostly lonely affairs in Cather’s fiction; instead, friendships are always the most vital relationships. Consider the charged bond between Jim Burden and Ántonia Shimerda in “My Ántonia” and the two clergymen in “Death Comes for the Archbishop.” Even in “Paul’s Case,” the intense 1905 short story that Taylor rightly deems “Cather’s first undoubted masterpiece,” the eponymous main character — whom we readers today certainly view as queer — yearns, above all else, to merge himself with beauty and art, to “chas[e] ‘bright Medusas,” to use Cather’s phrase, rather than content himself with ordinary life. Was the wish to “become a fountain pen and have done with it” something of a liberating fantasy for Cather? Probably.

Two summers ago, during my brief pilgrimage to Red Cloud, I was fortunate to be shown the place where Cather’s transformations began: the “story-and-a-half frame house” that her parents bought in 1885 for their growing family. I climbed to the attic dormitory and peered into the shadowy little room, “a corner of the L-shaped attic” that had been partitioned off for Willa alone. Her girlish flowered wallpaper was still mostly intact. As Taylor notes, the heroine of “The Song of the Lark,” Thea Kronborg — an aspiring opera singer and stand-in for the young Cather — dreams of her destiny in a fictional evocation of that very same room: “From the time when she moved up into the wing, Thea began to live a double life. During the day, when the hours were full of tasks, she was one of the Kronborg children, but at night she was a different person. … She had an appointment to meet the rest of herself sometime, somewhere. It was moving to meet her and she was moving to meet it.”

With great feeling and deeply informed perception, Taylor helps us readers realize anew the sustained effort it took for Cather to meet “the rest of herself,” in her novels and her life.

Maureen Corrigan, who is the book critic for the NPR program “Fresh Air,” wrote the introduction to the Vintage 100th anniversary edition of “A Lost Lady.”

Chasing Bright Medusas

A Life of Willa Cather

By Benjamin Taylor

Viking. 192 pp. $29