With work by 50 contributors, “(Not) Strictly Painting” is an impressive survey of recent output by local artists who are (mostly) painters. For regular visitors to the area’s visual-art venues, though, the McLean Project for the Arts exhibition may prompt sensations of déjà vu.

Painter-turned-sculptor Barbara Januszkiewicz’s tinted-plexiglass assemblage, which gives pure-color painting a 3D presence, resembles her piece in “Artina 2023: Queering Nature,” on view through Nov. 12 at Sandy Spring Museum. Sookkyung Park’s construction of hot-colored origami pieces, arranged in a circle to evoke the sun, is identical or very similar to her painted-paper sculptures shown at two Maryland galleries this year. Maremi Andreozzi’s two paintings of historical women in elaborate costumes, but with their faces in silhouette, are from a series recently featured at Adah Rose Gallery. And Cory Oberndorfer’s painting of frozen confections outlined by rough-edged blocks of color is essentially a smaller version of his mural outside Culture House.

All are worth seeing, or seeing again. But there aren’t a lot of surprises in this selection, whose guest juror is Tim Brown, director of IA&A at Hillyer.

The show includes a few entries that really aren’t paintings at all, including one of Kanika Sircar’s elegant ceramic flasks and an animated video from Ann Stoddard that responds to oppressive policing of Black youths. More typical, though, are painting-sculpture hybrids such as Judith Pratt’s red-and-black cut-paper piece, which droops on the wall like a soft rib cage, or Gayle Friedman’s color-field canvas, divided between planes of orange or yellow, atop of which are looped lengths of band-saw blade painted in the contrasting hue.

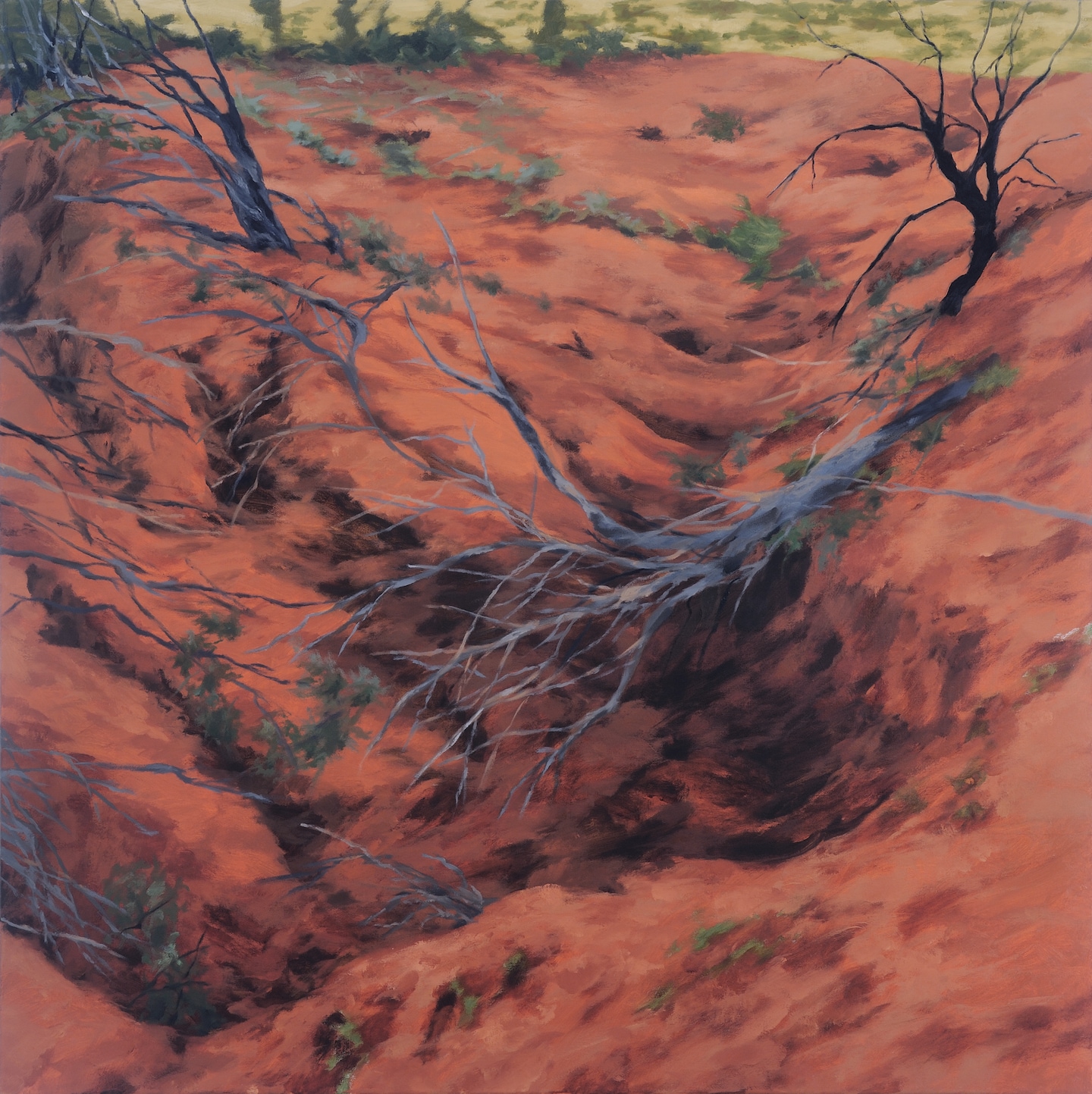

A few works that are essentially flat nonetheless conjure a three-dimensional experience. Joanne Kent elegantly arrays tufts of paint in shades of green, and Sondra Arkin positions white circles and black lines on pale blue to plunge the viewer underwater. More traditional are Freya Grand’s pair of realist nature scenes, which focus tightly on small areas of sea or earth. Her “Gully” demonstrates plain old painting’s ability to draw the eye into expertly simulated depths.

(Not) Strictly Painting Through Nov. 11 at McLean Project for the Arts, 1234 Ingleside Ave., McLean. mpaart.org. 703-790-1953.

Willy Fish Yowaiski

Executed over many years and with various techniques, Willy Fish Yowaiski’s abstractions are diverse in means but similar in effect. They’re mostly allover pictures with no central focus and a sense of potentially infinite expanses. His show at the Hyattstown Mill Arts Project was scheduled for 2020 before the pandemic intervened, which partly explains its title: “WillyVision2020 (So … Where Were We?).”

Most of the pieces are paintings, but the Maryland artist also offers collages and two sets of cubist-influenced drawings. The artworks’ tangled patterns suggest overgrown gardens, fractured mosaics or maps of rural areas — although perhaps the capillary-like strands of “Currents: Wing and Water” appear to resemble meandering two-lane roads primarily because the painting hangs next to a collage that incorporates fragments of actual maps.

The artist works mostly with acrylics but sometimes adds enamel or spray paint, and he seems open to whatever circumstance might shape his style. One of his more striking pictures, “Splendid Shadows,” is the indirect result of a broken arm: Unable to wield a brush, the artist used his fingers to render brightly colored, flowerlike gestures, which he later framed with areas of black. The result somewhat resembles a stained-glass window, which is apt. Yowaiski’s pictures don’t depict religious scenes, but they are luminous and constructed from intricately nested parts.

Willy Fish Yowaiski: WillyVision2020 (So … Where Were We?) Through Nov. 19 at Hyattstown Mill Arts Project, 14920 Hyattstown Mill Rd., Hyattstown. hyattstownmill.org. 301-830-1142.

Yumiko Hirokawa

The paintings in Yumiko Hirokawa’s show at the Watergate Gallery, “Letter to the World,” are in two modes: realist and expressionist. While quite different, both express the artist’s plea for peace.

A 2003 graduate of the Corcoran College of Art who returned to her native Japan last year, Hirokawa can apply paint with neoclassical precision. Her crisply detailed pictures of flowers, birds and clouds appear gentle and serene. But the birds are references to the proverbial canary in the coal mine, a harbinger of danger, and the clouds meld formations the artist saw over New Mexico with the ominous one her father glimpsed above Nagasaki in August 1945. The billowing “Sky of August” is dotted with gold-leaf daubs to represent lanterns lighted during Obon, the Japanese summer festival that honors the spirits of the departed.

Metallic leaf, usually silver, features more prominently in the expressionist works. These include ones in which white blossoms, leaves or olive branches are scattered or bent across shiny surfaces, as if nudged by wind. The looser, less literal pictures are closer to traditional Japanese paintings, but with silver foil taking the place of black ink. Evoking action but not conflict, they depict a world that is as idealized as the images are stylized.

Yumiko Hirokawa: Letter to the World Through Nov. 11 at Watergate Gallery, 2552 Virginia Ave. NW. watergategalleryframedesign.com. 202-338-4488.

Ram Brisueño

Although they’re set in a universe in flux, Ram Brisueño’s collage-paintings have an enduring sense of self. The works in “Young Mornings,” the Baltimore artist’s show at Zenith Gallery, are usually centered on a single heroic figure who appears to be either emerging from or receding into a teeming environment.

Blossoming plants envelop many of the people, some of whom may be transforming into other life forms. In “The Warm World,” a rare composition that includes two figures, one appears to be a centaur and the other has a blossom for a head, flowering atop an ornately body-painted Black frame. Also common are arrays of concentric dots, usually rendered in blotchy white or yellow, that surround a person like a halo, or a personal Milky Way.

Brisueño is self-taught, and his primitivist style can show more exuberance than finesse. Sometimes working from found photographic images, the artist seems to assemble his pictures intuitively. But that spontaneity suits his anything-goes scenarios, in which people can grow wings or stand in houses that sprout trees. Brisueño’s heavily layered tableaux approximate the unceasing fecundity of nature.

Ram Brisueño: Young Mornings Through Nov. 25 at Zenith Gallery, 1429 Iris St. NW. zenithgallery.com. 202-783-2963.