because i love the diversity (this micro-attitude, we all have it) is the curious and loaded title for a performance that had its United States premiere April 12-19 at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA). Rakesh Sukesh conceptualized, choreographed, and danced the work, co-presented by BOOM Arts. This performance was based on Sukesh’s experience as an Indian immigrant living in Europe.

I attended the afternoon performance on April 13 and found it delightful and challenging, offering as much wide-ranging nuance as its title suggested. The show dealt softly but expertly with raced, classed, and gendered intersections (spoiler: the term “micro-attitude,” in the context of the show, could be read as a stand-in for “micro aggression”).

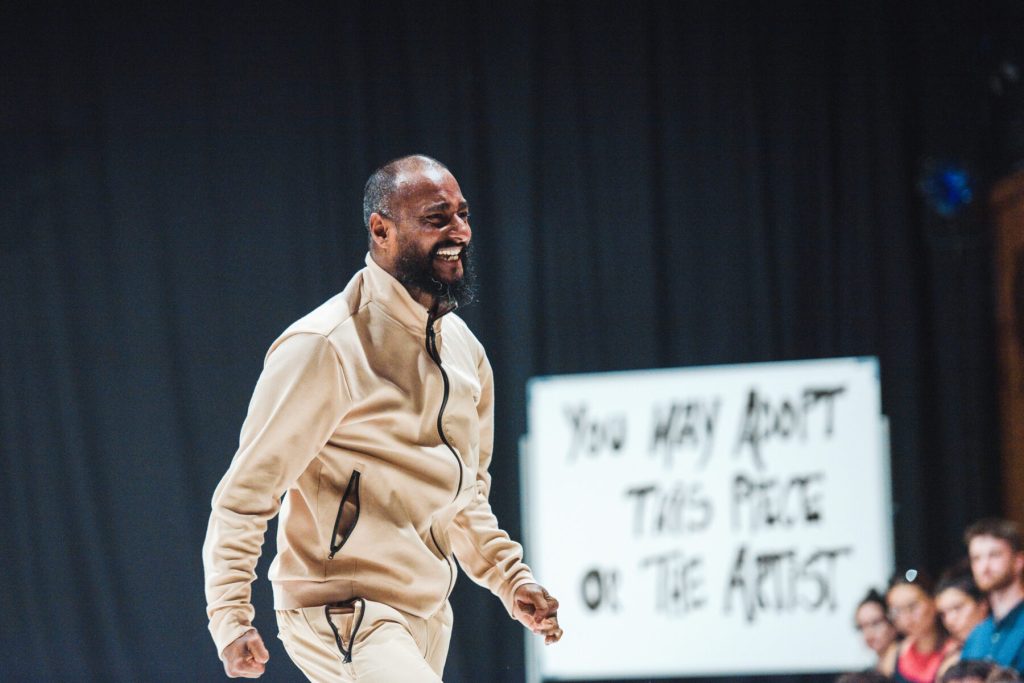

The performance began with a recording, a cascade of voices speaking over one another. Sukesh took the stage dressed in a beige Adidas track suit with black zippers. He acquainted himself with the audience through rhythmic dancing, stomping, and a few strategically added pelvic thrusts, all to the sound of what I thought might be Bollywood music. He smiled brightly with twinkling eyes. He then performed some wobbly ballet moves, slipping in a few hip thrusts that offered humor and pleasure to the form.

Sukesh pulled out a brown tapestry from behind a black curtain, which buffered the edge of the white dance floor upstage. Holding it over his torso, he set the scene, saying, “This is a map of India.” He used his foot to point to the lower region, his home state, Kerala, and went on to share the story of his early life:

Sukesh grew up in a family that made tapestries. He practiced Bollywood as a young person at the behest of his father, who thought it might boost low confidence. However, he found Bollywood’s behind-the-scenes culture disenchanting.

One day, Sukesh saw a picture of two people doing something “very strange” and learned from a friend that this was contemporary dance. Sukesh tried contemporary dance and found that “it felt great!” (He said this to the audience while doing a buoyant drop-swing, arms releasing over torso and then rising again.)

Sukesh’s affinity for contemporary dance led him to travel and work in Europe. He ventured to Germany first, but struggled to get a dance gig due to his lack of a visa. He eventually married a Swiss woman, saying that in Switzerland, ”They loved my diversity!” (an obvious callback to the show’s title). Sukesh demonstrated this “diversity” by jumping with flourish and charm, his story always articulated dually through voice and dance.

His contemporary dance work took him to many different countries, including Estonia. One day in that country, he noticed that he was being photographed while out and about with friends. Shortly thereafter, his face appeared on the news as the image for a campaign against immigrants from Africa and Asia, propagated by a right-wing agenda.

At this point, Sukesh’s story became more pointedly embroiled in the intersection of race and class — namely, the tired and all too familiar scapegoating of folks of color in class conflict. His face was used to fuel racist sentiments against immigrants who were said to be absorbing too many working-class jobs. This stood in odd contrast to Sukesh’s field of contemporary dance, which is commonly affiliated with the bourgeoisie.

During this moment in the performance, Sukesh began grabbing at his face frantically, as if he wished to escape it. He mentioned posting his plight on Facebook and receiving words of support from friends. However, one Estonian friend living in Austria responded sharply, writing about working hard, facing his failures. “If you can’t do the same,” the friend added sharply, “then you should just go back to your country.”

Sukesh began jolting movements and saying, yelling, “FUCK,” repeatedly and full of upset. From this point, his story brimmed with anecdotes of racist encounters he had experienced. In Italy, a family friend of his lover called him blue (since he is not Black). “Blue, blue, blue,” he said, stomping loudly. Somewhere else in Italy, he was mistaken for an Uber delivery person. The residue of these encounters seemed to rattle around in his body and cycle in the echolalia of his vocalizations.

The voice of Sukesh’s “friend” played over the sound system, a white woman named “Carolina” who said she really loves “diversity.” Carolina told a story about trying to befriend some African men and then feeling offput when she sensed their apparent sexual interest (in the meantime, failing to name her own racialized objectification in pursuing these friendships).

Throughout the performance, Sukesh also referred to his various marriages and girlfriends, the implication being that perhaps he was using them for emotional support and stability during his travels. And perhaps they, too, were using him for his “diversity” (soft language for exotification), like Carolina and the African men.

I cannot overstate Sukesh’s intelligence as a mover and choreographer. He insistently taught the audience Sanskrit words — some for yoga positions like “Adho Mukha Svanasana” (commonly referred to in the U.S. as “downward facing dog”) — asking us to repeat after him for pronunciation.

“You don’t need to turn everything into English,” he said. Every time his story would ramp up, he would break with movements. To the tune of “The Dying Swan” Sukesh performed exaggerated choreography of many desirable moves that commonly appear in contemporary dance. This included floor work, a martial arts kick, a split, attempted pirouettes, and an aerial from gymnastics (though his hands tapped down at its apex — failure was part of this dance). He moved as if trying to fill out these circumscribed forms while keeping his spirit suppressed, brooding. He ended in a handstand, chanting “Shanti, Shanti, Shanti,” settling back down.

Toward the end of his performance, Sukesh revealed that he comes from a lower-caste family in India and admitted that his ego compelled him to pursue contemporary dance in Europe. I thought about the impulse to don the mask of class privilege in bourgeois art circles, and how Sukesh faced the impossible task of toggling between the western art contexts he moved through and the complexity of his own being and ambition. He seemed to absorb everything inherited, put upon him, thrown at him unexpectedly during his travels in psychically piercing ways. When words would not suffice, he grappled with this through movement and sounding.

The performance culminated as Sukesh pulled out a large tapestry of material sewn together from many fabrics, which had been hiding behind the black curtain at the edge of the space. It ran from the floor to the ceiling, twisting up into the rafters and extending out across the stage, and it was mostly constructed of patterned blue material, but fading into a deep brown at its tail end.

Sukesh took off his sweaty beige tracksuit to reveal his naked form, ripped off a section of the brown fabric, and sewed a garment to wear on his lower half instead. The fabric matched his skin tone, revealing the shell of the Adidas tracksuit as a kind of uniform of western contemporary dance culture, coded with whiteness.

As Sukesh sewed his new garment, the voice of an Indian woman played over the speaker. “When we think of you, we feel sad,” she said in her language. Sukesh translated for the audience, noting that this was his “mother.”

Here, I felt the age-old plight of many artists whose families have little frame of reference for their achievements. I wondered if being a contemporary dancer, in particular — where financial stability is usually so much less than any success would suggest — means always feeling like a failure, no matter who you are.

Sukesh wrapped himself in the tapestry, the giant saree, with the help of an audience member, and called on Alessia Luna Wyss, the show’s dramaturg and set designer, for additional assistance. Sukesh also noted that the script for the performance was written by Marcus Youssef — and, in fact, these two collaborators held more integral roles in shaping the production than I can list here.

Perhaps it takes multiple people offering their many talents to tell a story like this, to build bridges between words, movements, sounds, textures that call up feelings too complex to spell out directly. As the performance indicated, Sukesh is merely one character of many in a much bigger saga, one that everybody still has a hand in directing.