First I received a notice from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs about enrolling in something called the Million Veteran Program, a genetic database. Do you want to join?

I think the prepared letter ended up in the waste basket, but then, later, having second thought about doing something to benefit other veterans, I notified the VA that I would sign up to participate in what the agency has called the largest such database in the world.

Then I got a call from Tessa Miller, a research coordinator at the VA Clinic in Santa Rosa. She scheduled an appointment for me on Monday morning, for a simple blood draw for research purposes, a brief interview, and the signing of a consent form. Fairly standard stuff.

I knew a little about the MVP, as it’s called for short, from a VA brochure, which described it as the agency’s “largest research effort that will help scientists understand how genes, lifestyle, military experiences and exposures” affect veterans’ health and wellness.

The program’s researchers want to study veterans mental health (the genetics of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders and suicide risk). They also want to help veterans everywhere make healthier diet and lifestyle choices, understand heart disease and cancer rates among veterans, male and female. Their discoveries, as I understood the program’s purposes, also would permit researchers to drill more deeply into Gulf War Illness, tinnitus, traumatic brain injury, kidney disease, Alzheimer’s dementia, COVID-19, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and more.

Eventually they were all selling points for me to help the 7.8 million living U.S. veterans (according to the Pew Research Center data) who served in the Gulf War and Vietnam War eras.

I could have signed up online — at mvp.va.gov, provide a blood sample, complete a survey about my lifestyle, general health and experience, give the VA access to all my health records — or gone to one of two Solano County’s VA clinics. One is next to David Grand Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base, while the other is on Mare Island, in 160/MI Building, 201 Walnut Ave., Vallejo.

But I decided I’d rather go in for the blood draw near my Sonoma County home, listen to VA employee outline the program for me, what would happen to my health records, and answer questions about medical privacy.

And Miller did.

I arrived at the clinic at 10 a.m. sharp and one of the first things she told me was that the VA reached its 1 million veteran sign-ups on Nov. 8, three days before Veterans Day. And since that time, the number, after the program’s start in 2011, had climbed, according to real-time data she showed me on her computer, to 1,007,755 on Nov. 27.

Miller said I could withdraw from the program at any time, if I wished, and my blood sample and its data would be destroyed at that time. And such a decision would not affect my existing VA benefits, she noted. If I wanted to withdraw or revoke my participation, all I had to do was contact the MVP, at mvp.va.gov.

Miller spent several minutes going over the program’s confidentiality guarantees: 1) All the program information is stored securely in the VA’s MVP central research database; 2) All samples and health information (VA and non VA) is coded (labeled in a way that does not identify me), and only select authorized MVP staff would be able to link the code to my name; 3) Researchers permitted to analyze my blood sample and data would not receive my name, date of birth, contact information or Social Security Number.

After signing the consent form electronically, Miller printed the form, which included my MVP identification number and where I enrolled.

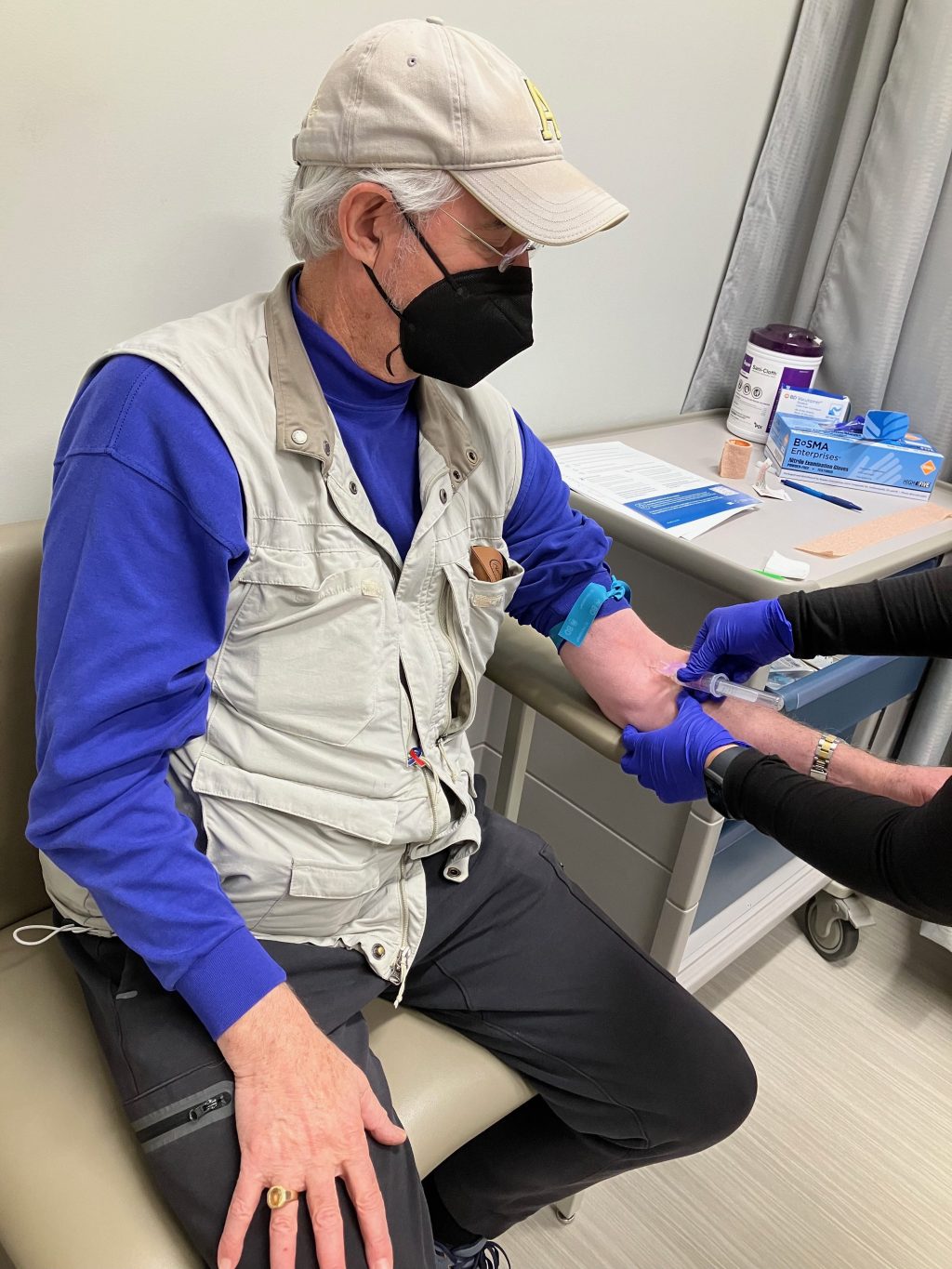

Then a phlebotomist drew 10 milliliters of blood from my left arm, then afterward wrapped up the needle insertion area with gauze and elastic tape. I thanked her and Miller for their time and returned home to finish my day’s assignments.

Later in the day, I learned why the VA program matters:

Medical researchers have been amassing large databases for genetic research, including genes that appear to give resistance to dementia and ones that most likely lend themselves to obesity. Such discoveries provide ways to understand such diseases and lead to the development of treatments.

While other large databases have been centered in Europe and involved few minorities, VA officials say the MVP database offers a glimpse into a more diverse population: 175,000 people with African ancestry and 80,000 Hispanics have joined the program. The database also includes 100,000 women.

And, according to VA data, the MVP has resulted in the largest database on nutrition in the world. To date, researchers have discovered the following: 1) Nuts — but not peanut butter — can lower a person’s risk of death from heart disease; 2) Five or more cups of white potatoes each week increases a person’s risk for coronary artery disease; 3) High levels of sodium, like table salt, and low levels of potassium increases a risk of heart disease; 4) Any kind of yogurt is good for a person’s health; and 5) A diet of mostly fruit, vegetables, and other plants — such as whole grains, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, and tea/coffee — may help us live a longer, healthier life.

Also, some treatments for chronic kidney disease are being developed through the MVP. It suggests the power of genetic research to transform patient care, VA officials say.

Perhaps no surprise, I also learned that suicide prevention is the VA’s top priority, as, according to VA research, an average 20 veterans die from suicide every day.

I served my country in uniform for a time. For me, Monday morning was a time to serve again. And to serve future veterans.