First Draft: A Dialogue of Writing is a weekly show featuring in-depth interviews with fiction, nonfiction, essay writers, and poets, highlighting the voices of writers as they discuss their work, their craft, and the literary arts. Hosted by Mitzi Rapkin, First Draft celebrates creative writing and the individuals who are dedicated to bringing their carefully chosen words to print as well as the impact writers have on the world we live in.

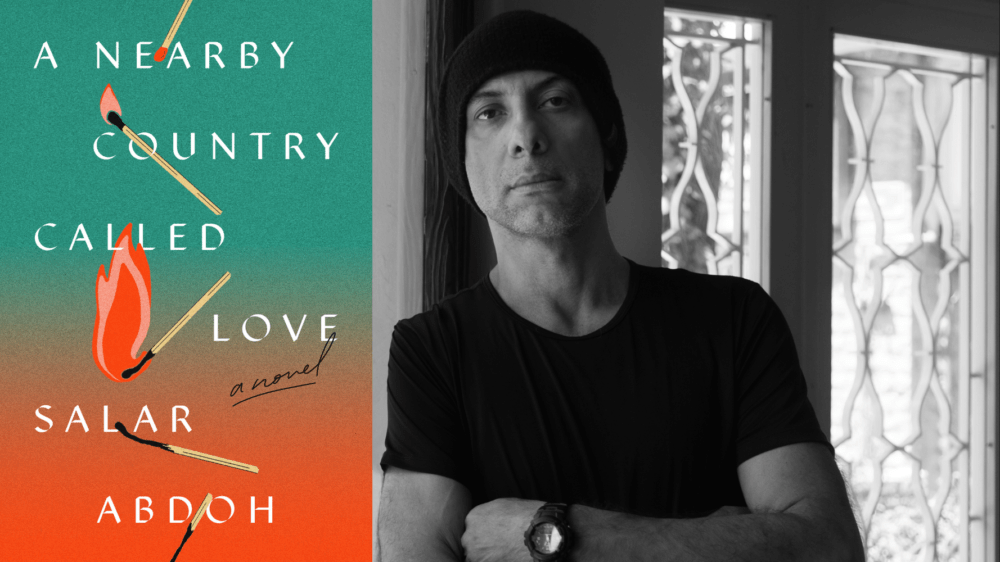

In this episode, Mitzi talks to Salar Abdoh about his new novel, A Nearby Country to Call Love.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Mitzi Rapkin: Can you talk a little bit about the women burning themselves in your novel, which is not just an incident that begins the book that these characters are really interested in, but it’s mentioned throughout the novel.

Salar Abdoh: When I started this novel, many things were on my mind, and I had been thinking about the fact, the reality of women and especially young women, and sometimes very young, young girls essentially, burning themselves. There would be periods, where there would be like copycat and once we entered the age of social media, it got worse, because then you know, it could be shared and some adolescent in a village who still has some access to social media would say, oh, so let me do this because I don’t have anything my life. But in general, what I was interested in, again, as a writer, but as a writer, who had had to travel a long distance. I had a long learning arc because of my background, you know, my father was in professional sports. That’s really what I thought I was going to be doing for the rest of my life for a long time. I didn’t come into the world I know automatically. I was not the studious type. I was always reading books, but my older brother, who I sort of write about in this book was. So, I came from a world of again, I have no other word for it, and very masculine. Machismo is a real thing in this world. A couple of things that I was troubled by in the world because I also now teach in academia in America, and I got back and forth. I thought there was a divide between what happens in academia in the West and the discourse that exists here and the absolute reality on the ground of much of the world. And it’s that reality, I’m a boots on the ground writer. My research is to just throw myself into a geography and see how people live and live with them. I didn’t have to read in a book or books about the situations of women or read about it in newspapers. I started to see women’s lives. And it’s not that I hadn’t seen it before or paid attention. But you know, as a man, you have to teach yourself, because everything in the world in the culture that you know, has pushed you towards lack of understanding. Everything you know, is about, you’re a guy, you’re from that place, don’t worry about these things. I had to learn to see and not just see, but see again, and again and again. So, when I saw what was happening to women, and the extreme case was when they felt like they had no recourse they were burning themselves, especially in the provinces. I become very disturbed. I started researching it a little bit. But that also led me to thinking about what women’s lives are in the world, you know, in a way that was very flesh and blood, not book material, not seen on TV. I wanted to see what it feels for a 12-year-old Afghan girl in the Badakhshan province to be married off to a 74 year old man and why she kills herself or why she risks the Hindu Kush mountains, to come to Iran to go to Turkey and somewhere along the way, she’s probably raped several times, you know, and these stories I started to collect. And the other thing that happened was that I started to translate a lot as a service to the writers in Persian in Afghanistan and Iran and other places. I would say four out of five things I translated were pieces by women, it just happened. I didn’t choose them, they came to me, and they have things to say. And I realized, my God, I’m translating these things, and I’m learning about these lives. And it’s not that I didn’t know it, but now I deeply know, it’s a part of my being, I can’t turn my head away from this. And I would not have been able to write A Nearby Country Called Love if I hadn’t been doing these translations.

***

Salar Abdoh is the author of Out of Mesopotamia, Tehran at Twilight, Opium, and The Poet Game, and editor and translator of the celebrated crime collection, Tehran Noir. He divides his time between New York City and Tehran, Iran. He is a professor at the City University of New York’s City College campus in Harlem, where he teaches in the English Department’s MFA program and also directs undergraduate creative writing. His new novel is called A Nearby Country Called Love.