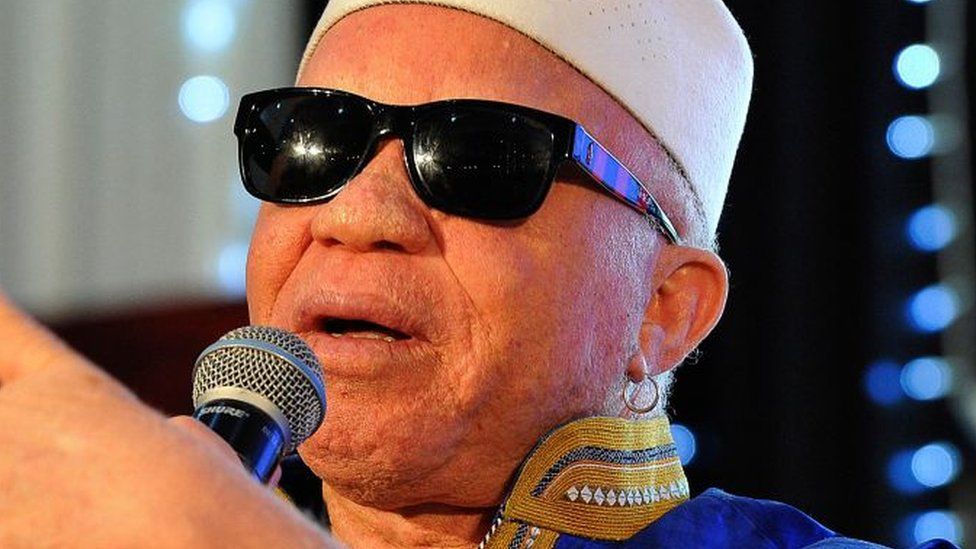

Shock. Bafflement. Scepticism. These were some of the reactions among a group of music fans when Mali’s much-beloved Salif Keïta – known as the Golden Voice of Africa – was appointed as a special adviser to coup leader Col Assimi Goïta.

The 73-year-old might be in semi-retirement and eclipsed nowadays by Afrobeats stars, but he was one of the pioneering giants of a generation that put African music on the global map.

After 50 successful years in the music industry, he remains influential, admired and well-known.

Keïta mixes traditional Mandé music with jazz, blues and Western music styles and was nominated several times for a Grammy for his infectious melodies and powerful voice.

He has albinism – and he has campaigned tirelessly against discrimination.

In 2005, the musician set up the Salif Keïta Global Foundation to raise awareness of the condition and speak out against a perception in some African countries that albinism is an ill omen.

People with albinism are often shunned and bullied – as Keïta was as a child – and in some countries, like Burundi and Tanzania, they are killed or body parts cut off and used in rituals.

Keïta’s dream as a child was to be a teacher – but he was denied the opportunity and told he “would scare the children”.

Keïta has raised funds from his concerts and donated proceeds of his record sales to his foundation to help with medical assistance of people with albinism – who are more prone to skin cancer and poor eyesight because of their genetic condition.

So why would Keïta take on such a role as special adviser on cultural affairs to a man who has led not one but two coups – the first in August 2020 and the second in May 2021?

Three years ago, there was significant popular support for Mali’s military junta when it seized power after mass protests against then-President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, who is no relation to the musician.

People had had enough of feeble leadership, corruption, economic hardship and chronic insecurity caused by an Islamist insurgency.

The musical mega-star was one of them – Keïta had been very outspoken in his criticism of IBK, as the ousted and late president was known.

In 2019, a video of Keïta, speaking in the Bambara language and addressing IBK directly, went viral.

He demanded that the president stand up against the former colonial power, France, which then had troops in Mali fighting the militant Islamists.

Keïta dismissed France’s President Emmanuel Macron as a “kid” – and falsely accused France of financing the jihadists.

He has also expressed doubts about Western-style democracy working in African countries.

“Democracy is not a good thing for Africa,” he told the UK’s Guardian newspaper in 2019. “To have a democracy, people have to understand democracy, and how can people understand when 85% of the people in the country cannot read or write?”

Keïta suggested that African people needed “a benevolent dictator”.

His views are out of step with most Africans – almost 70% of people in 30 African countries say “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government”, according to a survey published by research group Afrobarometer in May.

In Mali, however, 82% of people trust the military “somewhat” or “a lot”.

So Keïta appears to be in tune with the public mood in the West African state by supporting the junta.

He also served in the interim parliament – the National Transitional Council (NTC) – set up in December 2020 by the coup leaders as part of what they called a transition to civilian rule.

“This is a decisive time for Mali,” Keïta told Bloomberg news agency at the time.

“It’s very important that we correct the mistakes that have been made in the past.”

In what the junta would see as a success, the World Bank said in July that Mali’s economy has proved “resilient” despite high food inflation, cotton production being affected by a parasite infestation and sanctions imposed by the West African regional bloc Ecowas imposed to force the coup leaders to give up power.

But little progress has so far been made in achieving stability, with the monitoring group Acled saying violence in 2022 reached the highest levels it had ever recorded.

Soldiers dominate the interim parliament, and the presence of the Russian mercenary group Wagner has undermined the junta’s claim that it stands for Mali’s sovereignty and that it will be more effective than the French troops that have now left and a UN force that is winding down its operations.

On 31 July, Keïta stepped down from the NTC – he cited “purely personal reasons” while reiterating that he would remain an “unquestionable ally” of the soldiers, but did not mention Col Goïta.

His decision fuelled speculation in Mali that he was trying to distance himself from the junta, especially as it had just adopted a new constitution that entrenched the military’s grip on power.

But on 11 August Keïta accepted what was in effect a promotion – the post of special adviser on cultural affairs.

Col Goïta appeared to have appointed him to the post in an attempt to boost his popularity ahead of elections due to take place by February next year. There is intense speculation that the young and charismatic junta leader would transform himself into a civilian politician, and run for the presidency.

Many musicians speak out against military takeovers, oppressive regimes and democrats who turn into autocrats. Often at a great personal cost.

Zombie was a huge hit in 1978 for Nigeria’s Fela Kuti – it is a passionate rallying cry against the brutality of the then military regime, which detained and beat him.

Angélique Kidjo had to flee Benin in 1983 – because she refused to praise the work of the country’s then communist regime. She could not speak to her parents for six years because their phone was tapped.

But other musicians have aligned themselves with authoritarian rulers.

In the late 1970s, Mobutu Sese Seko – the-then ruler of Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo – paid the country’s biggest star Franco – the Sorcerer of the Guitar – and his TPO OK Jazz band to perform at huge propaganda concerts.

Franco’s “tightrope tango” as the New African magazine described his relationship with the authoritarian leader Mobutu “saw him alternate veiled criticism of the regime with outright paeans” or praise songs.

But mostly Franco was a praise-singer – and he became very powerful as a result. Mobutu gave him a nightclub and the country’s largest record-pressing factory – Franco proceeded to prioritise his own albums.

It was Guinea’s music-loving first President Ahmed Sekou Touré who in 1958 started the state sponsorship of bands in West Africa.

Touré was determined to help ensure a modern African music thrived – by paying for musical instruments, equipment and musicians’ salaries. Out of that came Bembeya Jazz – one of Guinea’s most successful bands.

Modibo Keïta, Mali’s first president, followed suit.

When he was overthrown in a coup in 1968, the plug was pulled on state sponsorship.

But the ex-president’s brother-in-law, Djibril Diallo, was a huge music fan – and the director of the Mali’s railway, which owned a hotel.

Diallo set up a band at the railway-owned hotel, in effect continuing the state sponsorship. The Rail Band was born in 1970 – from where Salif Keïta launched his career.

In the 1970s Keïta had to flee the political unrest in Mali for Ivory Coast.

Touré, still in power in Guinea, was a huge Keïta fan. In 1976 he bestowed a Guinean national honour on him.

In return, Keïta composed the track Mandjou – a praise song for Touré, even though by that stage he had become a brutal and bloody ruler. Keïta performed rearrangements of Mandjou throughout his musical career.

Now, as the Golden Voice of Africa takes up his role as special adviser to Col Goïta, the question is: will Keïta be a praise-singer or will he provide the sage and critical counsel that we have come to expect of the relentless anti-discrimination campaigner?

Penny Dale is a freelance journalist, podcast and documentary-maker based in London

Related Topics

- Mali

- African Music

- Music