I’ve lived in San Francisco now for more than five years, and until a few weeks ago I had never been to some of its most storied institutions. I have excuses.

One is timing — I arrived about six months before the pandemic. By the time I settled into my neighborhood and underwent a major life event (marriage), everything was locked down. My re-entry into the city and its culture has been slow, to say the least.

But the real reason I haven’t been to many of our most frequented (and beloved) sites is because no one ever invited me. That all changed last month when, finally, a friend asked me to join her and her two-year-old at the California Academy of Sciences.

Here’s what I realized: all you natives, long-timers, and everyone else more adventurous than me, you’ve been seriously holding out. Sure, we all know about these places, and find them adequate destinations for tourists, school field trippers, and visiting parents. But no one’s singing their praises nearly enough for the likes of me.

Allow me to step up to the mic. Whether you’ve never been, or are plenty familiar, 2025 is a great year to visit or revisit this holy trinity of science and nature: The Cal Academy, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Exploratorium.

They’re all accessible via bike or public transportation. And pro tip: with a library card you can score free passes to everywhere except the zoo.

The Academy of Sciences

The Cal Academy has occupied its Golden Gate Park site since 1916 in different iterations. The previous version, irreversibly damaged by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, had its wonders, like Sandy the great white shark who lived in the aquarium’s roundabout tank for five days. I wasn’t around for that, but I can’t imagine it surpassed the wonders of the current four-story indoor rainforest.

To call the rainforest a world of its own is not an exaggeration. Inside is a warm, wet, and wild place, entered via a series of doors and elevators like space travelers passing through a vessel’s airlocks. Once inside, pick your poison from an array of critters. Giant spiders weave elaborate webs along the walls. Butterflies nearly the size of your head flutter past. Between lush Amazonian plants, 250 colorful birds flit, while two giant blue macaws stand guard.

On the meandering journey, glass cases house gloopy frogs, neon-green snakes, and sun beetles whose patterns belong on a Fashion Week runway. Also: an oriente knight anole with the dopiest, happiest expression I had ever seen. If you need to escape Karl’s gray or the coldness of our summers, this is where you should go.

That’s just the start. The rainforest path leaves you one story underground, where the academy’s Steinhart Aquarium hosts more than 1,000 unique species. The first tank is a mind-bending marvel, a tunnel that shows off Amazonian giants, like the arapaima and arowana, that swim the flooded forest floor.

I spent a few minutes under the curve of the tunnel in awe, then moved on to a smaller, more local delight: the speckled sanddab, a pancake-flat fish with two eyes on one side of its body. Their exquisite camouflage fooled me into believing they were dead, so when they stirred it felt like witnessing a miracle.

These exhibits transported me but also stirred a bit of anger that no one had told me to visit before. Yet the real draw, the reason you absolutely need to visit this place, is Claude.

Claude is a rare albino alligator who arrived in 2008 from a Florida farm. In his first year, he lost a pinkie toe to Bonnie, the alligator meant to be Claude’s companion. (Bonnie was banished back to Florida.)

Compared to the feats of engineering around him, Claude’s habitat is simple. He rests in a modest artificial swamp atop his own heated island. He doesn’t perform the acrobatic feats of other Academy creatures. He barely does anything, in fact. That is exactly the draw. Claude is a sensory respite from the surrounding chaos.

His slow movements, his absence of color, his weird mischievous dinosaur grin, his unlikely coexistence with the snapping turtles in his habitat — he is the antidote to overstimulation. Claude completely transfixed me with his grace and patience and rarity.

I returned to him after another obligatory experience at the Academy: the “ Shake House” earthquake simulator. The 30-second taste – just a third of 1906’s minute and a half temblor — offered new appreciation for what people went through back then. Now, when the big one comes, I’ll have something to return to: the image of Claude floating in his tank. Peaceful and unbothered, safe and warm.

The Zoo

While it’s frequently the subject of controversy — most recently a scathing report, but also the Great Panda Debate, the deadly Christmas tiger escape, and the kidnapped lemur who was rescued in Daly City — the general consensus among people I’ve talked to is that the San Francisco Zoo is, well, a zoo. Worth a visit, perhaps, if you haven’t been.

I admit I went last month as much for the journey as for the destination: a bike ride through Golden Gate Park and then along the Great Highway. To be able to roll through the park’s stately greenery, past towering sand dunes, toward sea mist lingering in the distance and into an institution filled with animals from all over the world feels unreal, even when I’m in the midst of it. To live in San Francisco is to have endless access to the sublime. When the Great Highway becomes a park, this will be even more vivid.

I also had a destination to explore. Ticket in hand, my first encounter cured whatever indifference I might have brought with me: the African Savanna. I don’t know the average number of giraffes at zoos across the country, but SF’s herd (or “tower,” if you love quirky collective nouns) felt bountiful. The morning sun and the sweet goofiness of the giraffes made the savanna’s zebras — an animal I normally find menacing — seem more akin to Chris Rock’s Marty character in Madagascar.

From there, I meandered around the country’s largest outdoor lemur habitat. I confess I’ve already had peak lemur experience at the Albuquerque Zoo in 2019, when I got to feed them skittles and feel their weird rubbery hands as they jumped on me. Although slightly jaded, I did love scanning for the seven varieties hiding among trees and climbing to impossible heights.

I spent more time at the Gorilla Preserve, getting serious side eye from Oscar Jonesy, the 43-year silverback known for patrolling the domain. While Kimani, the youngest of Oscar’s troop, searched the grass for fancy cauliflower and fresh carrots, Oscar kept watch. Especially on me. The eeriness of my genetic predecessor refusing to smile or gesture back made me uncomfortable. (Even Jane Goodall prefers dogs as her favorite animals because she says chimpanzees are too human-like.)

Despite these encounters, I doubted I’d be able to make a glowing report. While I loved finding a sleeping fossa curled up like a donut and the peacocks on the loose, the zoo wasn’t as gleaming as the Academy of Sciences (a tough bar to meet), and there wasn’t much buzz from a sparse Wednesday morning crowd. October’s report, among more serious accusations, called the zoo “uninspiring” from a visitor’s perspective; I didn’t want them to be right.

Then I met Callista.

Callista is a 40-year old Andean condor, the largest flying bird of prey on our planet. I gasped out loud at her sheer size, and when she spread her nearly ten-foot wingspan, my instincts told me to back up. But I couldn’t move. Callista looked like a creature pulled from the underworld, equally worthy of respect and fear with her Satanic red eyes and regal white plumage circling her neck. Her very species borders on mythical, facing various threats to its existence since the 1970s. (A zoo official told me Callista isn’t helping the cause; since arriving in 2016 she has refused a mate.)

That wasn’t the only face-to-face encounter the zoo had in store for me. In the Cat Kingdom I had Jimmy G., the resident snow leopard, all to myself. As it came right up to the glass between us, this elusive-in-the-wild big feline looked like it could rip me apart but also had the bouncy energy of a house cat.

After a stop to admire the bizarre giant anteater, I was lucky to catch a rare winter glimpse of the grizzlies. Instead of a state of torpor (a quasi-hibernation), they were out in the sun whacking each other with their paws. Iif their claws look that large from several yards away, I cannot imagine how terrifying they are up close.

I understand that not everyone loves zoos. Some even find them inhumane. But I left in awe that I could be so close to these rare creatures — not through photos or videos but alive and out in the world. This is why we need these institutions.

The Exploratorium

My last stop on last month’s tour was the Exploratorium, a place I believed was only for children. And while it is definitely kid-friendly, you don’t have to be one or have one to be entranced.

I braved it on a Saturday afternoon, and it was as interactive and science-y and full of children as I expected. What I didn’t expect was the amount of art on offer. Before I even got my ticket, I was captivated by a preview of Maarten Baas’s 12-hour video “Sweepers Clock.”

As I ventured deeper into the museum, the focus shifted to the more tactile and physical, the teachings less philosophical.

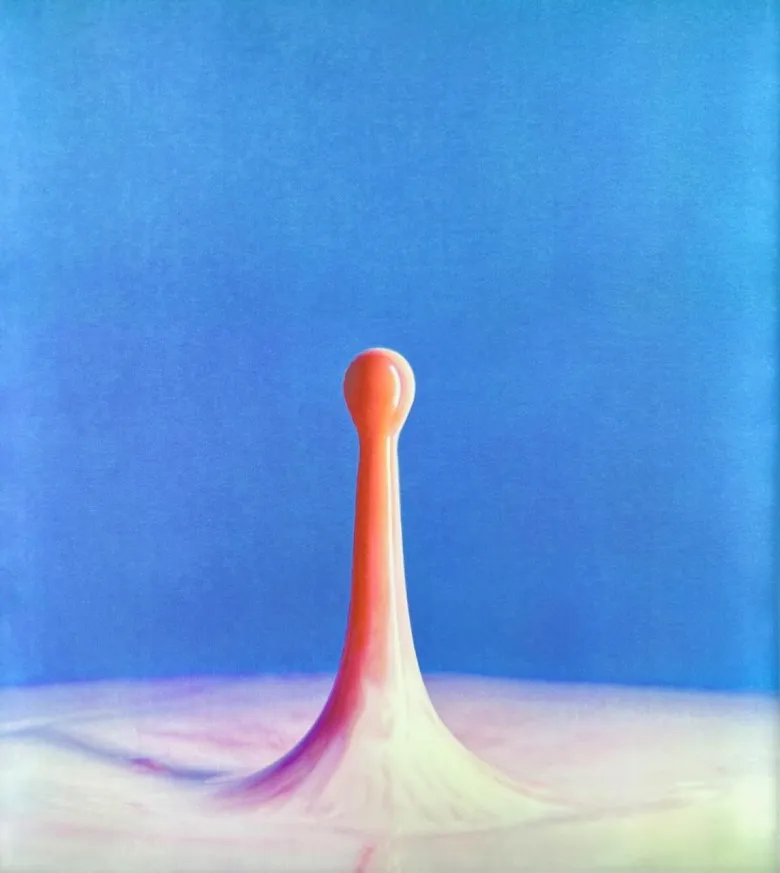

As I made my way down the long expanse of Pier 15, which the museum occupies in full, I was drawn to other thought-provoking pieces, such as Alma Haser’s “Clinton and Lee (1 & 2),” about the genetic variance of twins, and Harold Edgerton’s groundbreaking slow-motion capture of movement: a falling drop of milk, a bullet through a balloon. I could have been at SFMOMA. As someone who is not a tinkerer or particularly science-minded, this was a welcome surprise.

But yes, this is a science museum, and you immerse yourself in physics, biology, ecology, and chemistry. It was loud, energetic, and just as compelling to watch others play around in as it was to play around myself. This is the place I took the fewest pictures. You have to have your hands free and your mind present.

I began in the Human Phenomena section, where I found explorations of emotions, gender, and social interactions both playful and poignant. Two young kids were in deep discussion about the contents left behind on the “give and take table.” A small booth offered videos of people’s aural memories, including a touching story about the sounds of the bus in the Mission District. As I ventured deeper into the museum, the focus shifted to the more tactile and physical, the teachings less philosophical.

The Exploratorium reminded me of a beloved museum in Chicago, where I used to live: The Museum of Science and Industry. Yet what puts the Exploratorium in a class of its own was its awareness and use of place. At Pier 15 (relocated there from the Palace of Fine Arts in 2013), most of the museum juts out above lapping Bay waters, and its outdoor exhibits take advantage — an echo tube reverberates with tidal sounds, and a solar-powered water gun sprays mist.

At the far end, which seems halfway to Treasure Island, a camera obscura reflects stunning Bay Bridge views (albeit upside-down), and environmental exhibits offer viewing scopes of the water and displays of its tide cycles. What a privilege we have to be immersed in this, and what a way to learn about our home.

I made a mistake, though. I went to the Exploratorium alone. Much of its interactivity depends on the presence of at least another person. It encourages connection, which I witnessed as families, couples, and friends goofed around with magnets and mirrors and sound and ice.

Still, I found plenty to occupy myself, and I also found a companion when I needed a break from the overwhelming array of exhibits and activities. In a tank of elaborately bred goldfish, a sea snail glided along a leaf, slow and serene — another marvelous creature to pull me along my journey of San Francisco exploration.