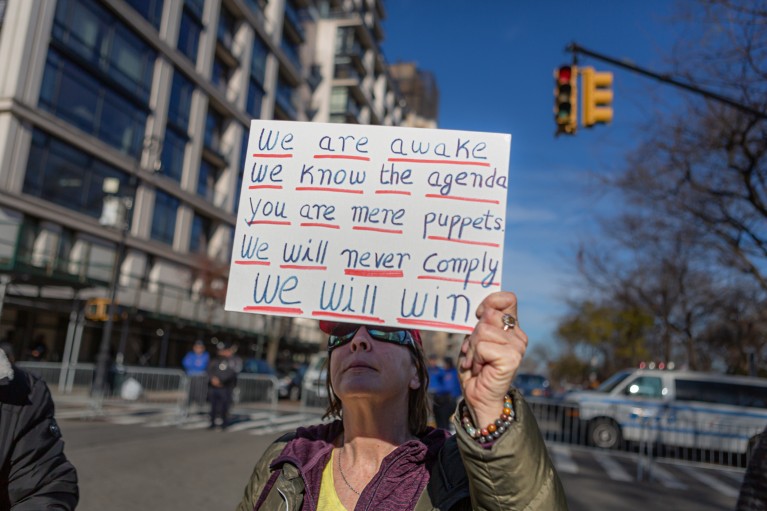

An anti-vaccination protester in New York City. Researchers are aiming to improve public trust in science by discussing uncertainty in their communications.Credit: Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/LightRocket/Getty

“Twenty seconds, professor, and no long words.” This is what a BBC producer once told Ian Fells, a chemical engineer at Newcastle University, UK, shortly before Fells was due to appear on a live broadcast. It was more than 30 years ago, at a time when few researchers were trained in how to condense science into sound bites, while staying true to the accuracy of their message.

Today, that challenge could be even bigger. The smartphone makes every researcher a potential writer, audio producer or broadcaster. Although many scientists have taken to communicating directly with the public, others are afraid to do so, not least because social-media platforms offer few guardrails or protections against disinformation. Another reason for their hesitancy is that principles that are fundamental to research — such as the scientific process, uncertainty around the results and the context — are difficult to fit into fast and short content formats.

Science must protect thinking time in a world of instant communication

Rhys Morgan, head of research policy, governance and integrity at the University of Cambridge, UK, has a fairly radical — or at least unusual — proposal. In a report published last month by the League of European Research Universities (LERU), a network of 24 institutions, Morgan proposes that public-facing science-communication work should adhere to the same research-integrity principles that are used for scholarly publications, and suggests that universities should support scientists who do so (see go.nature.com/4hxw4ag). In journal articles, researchers describe the methods used to obtain their findings and whether, for example, animals or artificial-intelligence tools were used in experiments; they explain how a finding fits in with the current knowledge in a field and declare conflicts of interest.

The idea deserves more attention from universities, companies and campaigning organizations — all of which are now much more involved in science communication than at any time in the past. It might not work in all contexts and there will be challenges to its implementation, but the concept should be discussed more widely.

There’s a view in the world of professional communication — for example, in companies that provide media training — that people prefer certainty to uncertainty. There are also studies that support this idea, not least the work of Daniel Ellsberg (published before he became famous for revealing a classified US study on the Vietnam war). The problem with emphasizing certainty as the default option when communicating science to a wider audience is that this is not how researchers discuss their findings in scholarly journals. In such instances, data are often communicated as a range, with levels of confidence in the results. Most researchers are careful not to overstate a finding, or use language that could be misinterpreted to mean certainty. Communicating results that sound certain when they are provisional could also harm a researcher’s reputation. Public trust in science, already under strain in many countries, could be further reduced (C. Dries et al. Public Underst. Sci. 33, 777–794; 2024).

Bring PhD assessment into the twenty-first century

The LERU report doesn’t go into how Morgan’s proposals could be implemented. But there are important implications, for corporate, government and university media offices. Many press officers work closely with scientists to ensure science is communicated accurately both on social media and in conventional mass media. They go out of their way to find researchers who have knowledge about and passion for what they do. However, at some institutions, staff members have fewer resources to communicate research results, compared with in the past, according to a 2022 report on the changing role of university press officers by science-communication consultant Helen Jamison for the Science Media Centre in London (see go.nature.com/3ccqxba). This is in part because many senior leaders in universities regard press-office communication as mainly about boosting their institute’s profile and reputation. Morgan and Jamison’s reports suggest that scientists need to be supported better by their institutions and recognized for their efforts in research communications, too.

Communicating uncertainty is often difficult, but there are tools and research available to those willing to try. ‘How to Communicate Uncertainty’, a 2020 report by researcher Dora-Olivia Vicol at the University of Oxford, UK, summarizes some of the literature nicely and provides helpful suggestions, such as how to effectively discuss a range of values and what the impact on audiences is when different words are used to describe uncertainty (see go.nature.com/3ufox9j). It was published by a consortium of fact-checking organizations: Africa Check in Johannesburg, Chequeado in Buenos Aires and London-based Full Fact. This shows that the ideas proposed by Morgan were already on the radar in this communications sector.

Science communication can do more to embrace uncertainty. It’s up to everyone who talks about research to consider describing both the process and the outcomes of the work — even in a 20-second sound bite with no long words.