Today, a simple internet search lets those in the LGBTQ+ communities find each other and welcoming establishments. But it wasn’t always so easy.

Even as gay culture was beginning to gain wider visibility in the 1960s and ’70s, especially in cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, knowing who would be friendly was hard. That’s where gay travel guides came in.

They worked like the Green Book guides designed to make travel safer for Black people or the vacation guides to steer Jewish people to friendly locations. For gay people navigating potentially fraught encounters, these pocket-sized guidebooks listed bars, hotels, restaurants, and even churches across the United States that were either frequented by the gay community or accepting towards gay patrons.

The most well-known guidebook of the time was the Bob Damron Address Books. These yearly guides were published by its eponymous author, a Los Angeles native who penned the first issue in 1964.

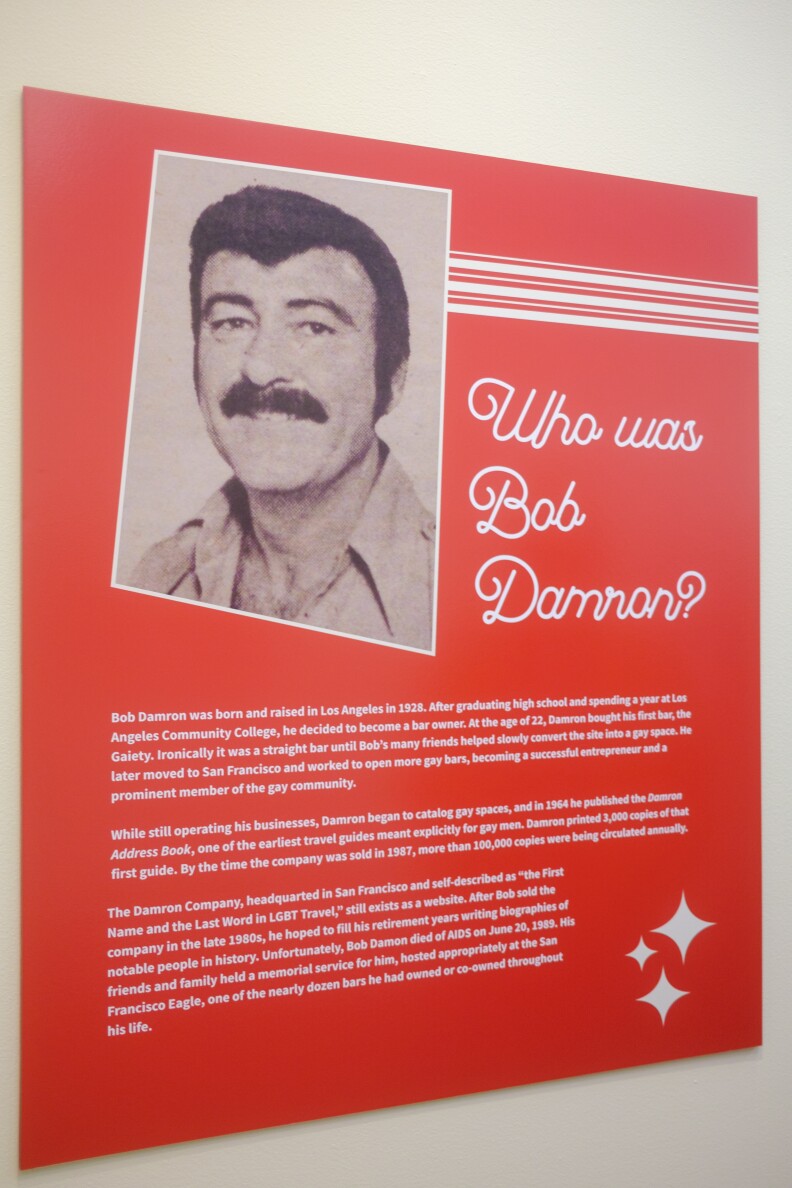

A picture of Bob Damron, the man behind the Damron Address Books, on display at the Muzeo in Anaheim

Courtesy atomicredhead.com

)

About the Damron Address Books

There were several different types of gay travel guides throughout the 1960s. By far the most popular, and the one to set the standard for the genre, was the Damron Address Book.

Bob Damron was born in Los Angeles in 1928 and later moved to San Francisco where he opened several gay bars, becoming a prominent businessman in the community.

The guides he would later become known for, which started as a side project, were of a collection of gay bars he would visit on his trips across and outside of San Francisco. The first Damron Address Book was published in 1964, and Damron would add new listings of LGBTQ friendly spaces every year.

An issue of one of the Damron Address Books, a 1991 issue of the Gayellow Pages, another well-known gay travel guide, and a ticket from the San Diego Eagle, a gay bar

Courtesy Clark Silva

)

Damron’s guides were distinguished from his contemporaries, especially in the early years by one key difference: He made a point to visit every location he included.

Eric Gonzaba, assistant professor of American Studies at Cal State Fullerton, said that gave Damron a connection with owners and patrons and made it possible for him to keep the new editions of the book as up to date as possible.

Another unique feature of Damron’s guides was his letter coding system.

If a bar listed in the guide had a “B” next to it, readers would flip to the front of the guide and see that “B” indicated that that particular bar was “frequented by Blacks” or gay African American men. Other letters would notify if a place was more popular with lesbians (what was originally signified with a “G” for “girls”, but has been updated to an “L”) or if customers were both gay and straight with the signifier “M” for “mixed clientele,” said Gonzaba.

“His letters didn’t always have to do with clientele,” said Gonzaba. “Sometimes it was very practical information. If you were a gay person and you wanted to go to a bar and play pool, he included the letters “PT” for there being a pool table there.”

A national project to map the gay guides

The entrance to the Mapping the Gay Guides exhibit at the Muzeo in Anaheim, Southern California

Courtesy atomicredhead.com

)

And it’s that level of detail that’s now the basis for a new new digital history project called Mapping the Gay Guides. The joint project between Cal State Fullerton and Clemson University is using every business and place mentioned in the Bob Damron Address Books from 1965 to 2005.

“We’re building these online maps to see if we can learn something about the gay community and the history of the LGBT community in the United States,” said Gonzaba.

Gonzaba said Damron’s guides provide great context, giving those studying the history a better understanding of both these gay spaces and the cities they were in.

Along with Amanda Regan, his project co-director and a Clemson University assistant history professor, Gonzaba has already mapped Damron’s books through to the 1980s, publishing the results online for public viewing.

Where to see an exhibit on these guides

Mapping the Gay Guides is also the focus of a new exhibit at the Muzeo in the city of Anaheim. The exhibit, now open through June 23, specifically showcases LGBTQ+ friendly spaces cited by Damron that are located in Southern California, including Orange County, Long Beach, and San Diego.

“I think a lot of people maybe know, or expect, a lot of gay history from Los Angeles,” said Clark Silva, co-curator for the exhibit. “But I think it was good for us to show kind of the gay history of the communities that we’re in and around” outside of Los Angeles.

The exhibit starts with a prehistory of gay culture before the guides were in print. This includes information about police raids and the difficulty of navigating through life while in the closet, said Silva.

After the Supreme Court ruling of One, Inc. vs. Olesen in 1958 that gave free speech protections to the gay press and gay publications, travel guides and other LGBTQ+ print material exploded, including the Damron Address Books.

A display of other gay and lesbian print material at the Mapping the Gay Guides exhibit

Courtesy Clark Silva

)

However, Gonzaba said that what visitors of the exhibit will notice is that these gay guides have very little indication that they are for the gay community.

Another thing Gonzaba wants people to notice is their size.

“They’re meant to be tiny so they can fit in your pocket, and that tells you, one, that they were meant to be traveled with,” said Gonzaba. “But another thing that it tells us is that they were meant to be hidden, right? Because it was quite dangerous to be openly gay in the 1960s and even into the 1970s.”

The exhibit also displays the rich gay history of Southern California. Separated into specific cities, visitors can learn about the gay bars in L.A., the gay friendly hotels in Palm Springs, the bathhouses in Long Beach, the cruising culture in San Diego, and the gay churches in Orange County.

“I think people who come to the exhibit are surprised that it’s not just a list of gay bars,” said Gonzaba. “That the gay travel guides talk about all sorts of businesses, all sorts of places of gathering that a lot of people just are unaware of.”

Both Gonzaba and Silva note that most of the Damron Address Books come primarily from the point of view of a gay, white, cis-male perspective.

“Bob Damron didn’t make racial designations for places until later, so very early places aren’t going to make the distinction between who comes to them,” said Silva.

How to see the exhibit

When: The Mapping the Gay Guides exhibit is open now through June 23

Location: Muzeo, 241 S. Anaheim Blvd. Anaheim

Phone: 714-765-6450

Hours: Wednesday through Sunday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Cost: General admission $10 | Anaheim residents $8 | Seniors and children 4-15 $7 | 3 and under are free

The importance of mapping one’s history

The advent of the internet and other cultural shifts have made the Damron Address Book, and gay travel guides on the whole, somewhat obsolete. Silva says those changes have fundamentally changed gay life.

“One of the issues that we talk about is the disappearance of places, and it’s mostly through a mainstreaming of gay and lesbian and queer culture,” said Silva. “You don’t have to have the gay bar anymore. Lots of bars, especially out here in Southern California, kind of move in between, straight bars having gay clientele, gay bars having lots of straight people come to them.”

Gonzaba said that by looking back at these guides, people can learn a lot about the different trends and historical geography of the gay community in the United States, something he says too few people know.

Gonzaba said when he travels, he finds a lack of historical knowledge about gay people in cities across the U.S. and abroad.

When he asks tour guides if they know about any of the local gay history there, most of the time people respond by saying there just isn’t any. Which Gonzaba, and most people in LGBTQ+ communities know isn’t necessarily true. People just haven’t been looking for it.

“These gay travel guides, they really show us that, at least for a lot of gay men and women, visibility was something that they wanted,” said Gonzaba. “They wanted to find one another for camaraderie, for friendship, and sometimes for sex. And that’s a really important lesson that these gay guides tell us, is that people were constantly yearning to find one another.”

What questions do you have about Southern California?