For well over a century, successive avant-garde movements have made it their mission to interweave art and life. Dadaists, Bauhaus proselytes, Russian Constructivists, De Stijl minimalists, Italian Futurists, Fluxus polymaths, hip-hop fashion moguls — all tore down fences that kept popping back up between object and experience, the refined and the everyday.

Yet it’s the inexplicably neglected Sonia Delaunay who did it longest and best. “I have lived my art,” she said, and a spectacular new survey at the Bard Graduate Center in New York demonstrates how: with all-consuming passion and pride. Delaunay spent most of the 20th century producing furniture, playing cards, textiles, theatre costumes, fashion, paintings, mosaics and her own persona, all of them saturated in kaleidoscopic hues. “Colour is the skin of the world,” she declared.

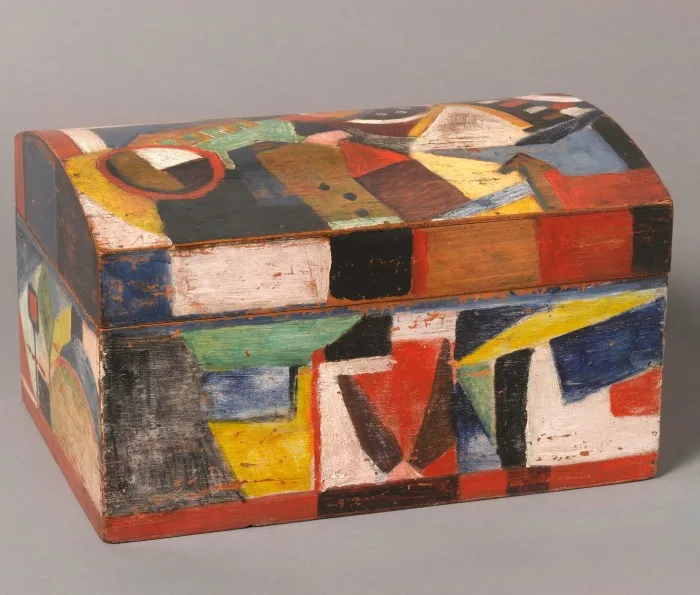

With more than 200 objects, Sonia Delaunay: Living Art is at once exuberant and weighty. She thrived on simultaneity, a term she used to mean the juxtaposition of disparate textures and colours, but that might also refer to her work habits.

A “Simultaneous Dress” from 1913 greets visitors with a deluge of funky patchwork that she planned, cut and sewed herself. Hung on the wall, it could be an abstract painting. Ideally, though, it would be displayed the way Delaunay did: by wearing it to dance the tango in a seedy Montparnasse club called the Salle Bullier. Her friend the writer Blaise Cendrars commemorated the sight in the poem “On Her Dress She Has a Body”.

Together, they fabricated what they describe as “the first simultaneous book”, 22 panels of text by Cendrars and illustrations by Delaunay that could fold up like an accordion or unfurl into a seven-foot column — which is how it is exhibited here. One glance at the fully extended “La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France” (“Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Joan of France”) yields a jolt of polychrome pleasure. Move in close and (if you read French) you can follow a surreal rail journey from Moscow to Paris via China and the North Pole. Delaunay’s luscious forms tumble down one flank, alongside coloured text that rolls across the other, mimicking the rhythms of a voyage. No matter how many times I see this piece, it slays me with joyful beauty.

Born in Ukraine in 1885, Sara Stern, as she was known to her working-class Jewish parents, was moving up in the world by the time she was five. Her uncle took her in, moved her to St Petersburg and raised her as a member of the haute bourgeoisie. She spent summers in Finland, attended art school in Karlsruhe and learnt German, French and English.

By the time she was 21, she had landed in Paris, where she met and married the well-connected art dealer Wilhelm Uhde. It was a marriage of convenience: he was gay; she needed a rationale to remain in Paris. Uhde, who mounted her first solo show in 1908, also introduced her to Picasso, Braque, Vlaminck — and to Robert Delaunay.

Sonia fell instantly for Robert, her great love and kindred spirit. “His aggressiveness filled me with delight,” she recalled, and it didn’t take long for her to get pregnant, divorced and remarried. Their partnership was artistic as well as romantic. When the first world war stranded them in Spain, Sergei Diaghilev commissioned sets and costumes from them for the Ballets Russes production of Fokine’s Cléopâtre at the London Coliseum. The glittering outfits, trimmed with cloth-of-gold appliqué to shimmer under the stage lights, complemented and enhanced the dynamism of the dance.

In Madrid she launched her fashion and design career, opening the boutique Casa Sonia in 1918. Returning to Paris in the early 1920s, she debuted a new store, which catered to a chic bohemian crowd. As usual, she kept her work going on multiple tracks, collaborating with an assortment of Surrealist poets on a series of “robe-poèmes”, with witty lines of verse embroidered on to legs, sleeves and torsos so that literature could literally be moving.

The show clarifies that Delaunay was a businesswoman with a canny sense of branding; early on, she fashioned an instantly recognisable identity, her name brightly printed on book covers, posters and pamphlets. The apartment on Boulevard Malesherbes that doubled as her headquarters was a Gesamtkunstwerk. Every item — rugs, curtains, furniture, hand-embroidered upholstery, even the clothing to be worn in its rooms — harmonised with her bold aesthetic.

History kept trying to thwart her, and she kept scrambling to her feet. The Depression killed off her upscale shop, but she rallied, plying Amsterdam’s luxury department store Metz & Co with fabrics all through the lean years. When the imminent German invasion of Paris once again displaced the Delaunays, they fled to the south of France.

Robert died of cancer there in 1941, and Sonia spent many years promoting his work rather than her own. She succeeded all too well: his paintings overshadowed her efforts to collapse hierarchies between fine art and craft. Hers was the more radical vision, but it faded into the background.

In some ways, the most invigorating section of the show is the last. She returned to Paris alone after the liberation and dabbled desultorily in abstract painting and textile products. That’s where the story might have wound down, if France’s government and cultural luminaries hadn’t discovered what a national treasure she was. From the 1950s on, she was peppered with honours, saw old dress designs newly realised and fulfilled commissions large and small.

Belated recognition triggered a creative rebirth. In 1959, she produced the first of two dozen tapestry designs that would carry her through most of the rest of her life. The one displayed here, from the mid-1970s, is a wall-sized marvel composed of her signature concentric circles. She also conceived one of the show’s sparkling centrepieces, a luminous mosaic inspired by the arts of Byzantium.

Perhaps most satisfying to the artist who aimed to collapse distinctions between precious and popular, the vivid geometric clothing she had invented decades before found a new, hip life. Marc Bohan, a couturier for Christian Dior, used one of Delaunay’s designs from the 1920s for the balladeer Françoise Hardy to wear in a 1968 television programme. In a floor-length black-and-white dress, like a deconstructed street map, Hardy sings “Comment te dire adieu” as she ambles through a landscape of panels painted in the same sleek shapes.

Delaunay observed that her art had appeared “40 years too early”. But the times had finally caught up, which for a while made her newly cutting-edge. She died in 1979 at 94, ready for the next round of rediscoveries, which continue coming along every decade or two. Maybe this one will stick.

To July 7, bgc.bard.edu

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen