CHAMPAIGN — The number of active satellites orbiting Earth has increased dramatically in recent years, surpassing 10,000. With so many objects in orbit, space traffic control is necessary to prevent collisions.

“Though there is a lot of space in space, it’s starting to get crowded,” said Dave Leake, former director of Staerkel Planetarium at Parkland College and co-founder of the Champaign-Urbana Astronomical Society.

Typically, when spacecraft are at risk of collision, operators communicate with one another to decide who’s going to move. NASA and SpaceX recently tested an approach to automate this process for their spacecraft.

Astronomy experts in Champaign-Urbana see this as an important development, in light of the significant increase in space traffic.

“Collaborations like this are going to be more and more important in the future as Earth-orbit gets a bit more crowded,” Leake said.

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites make up the majority of active satellites. The first launch of operational Starlink satellites was in 2019, and many more launches followed since. The satellite constellation’s low-Earth orbit allows it to provide low-latency Internet with minimal delay or lag, as the data travels a shorter distance compared to other Internet satellites.

In 2023, NASA launched the Starling swarm with the objective of testing technology for cooperative spacecraft. Having completed its initial mission in 2024, it now works with SpaceX’s Starlink to test improved systems for space traffic.

But space traffic with active spacecraft is not the only concern sparked by the drastic increase in objects orbiting Earth.

Collisions and space debris

Space debris refers to the human-made clutter in space, such as inactive satellites, old rocket parts or debris from colliding objects.

Leake points to a collision in 2009 between an American commercial satellite and a Russian military satellite. Both of the satellites were used for communications, but the Russian satellite had been deactivated years ago and remained orbiting as space debris.

“They hit each other at 26,000 miles per hour, which can result in something called the ‘Kessler Effect,’” Leake said. “This means the pieces of each satellite are sent away at random trajectories and each could be a risk for other satellites.”

That was the first collision between satellites in Earth-orbit. The European Space Agency estimates there have been more than 650 “break-ups, explosions, collisions, or anomalous events resulting in fragmentation.”

Even small bits of debris can be damaging to spacecraft, given how fast things move in orbit.

“You worry about the things that are smaller,” Leake said. “I mean, it’s like bullets out there in space.”

The ESA estimates there are more than 40,000 pieces of space debris greater than 10 centimeters, more than 1 million between 1 and 10 centimeters, and 130 million between 1 millimeter and 1 centimeter.

While there is not yet a concrete solution for cleaning up Earth-orbit, space agencies around the world are working on potential methods.

Interference with astronomical observations

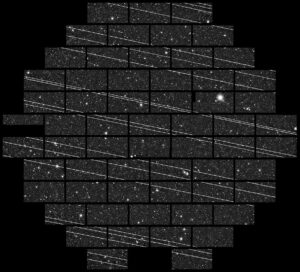

Astronomers often work with long-exposure images, using cameras to capture light over an extended period of time. This is like taking a photo using a phone’s night mode, which can require holding the phone still for several seconds. If someone walks in front of the camera while the photo is being taken, they may appear as a streak across the image.

As Earth’s orbit fills up, astronomers are more likely to see streaks from highly reflective satellites across their photos.

“Whenever you send up a satellite, you are sending a mirror into the sky,” said Liam Nolan, an astronomy graduate student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “The sun is no longer visible over the horizon, but the light then is coming up at a satellite and then getting reflected back toward Earth.”

That means satellites often appear in long-exposure images as streaks of light across the night sky, obstructing the view of celestial objects in line with the satellites’ paths.

Qiaoya Wu, another U of I astronomy graduate student, has personal experience with satellites photobombing the stars.

“You can see a lot of stripes,” Wu recounted. “You have to apply additional methods to extract the stars you are looking at.”

Astronomers around the world have been raising concerns about these obstructions, especially in recent years.

But Nolan has even greater concerns about a different source of light interference.

Light pollution on Earth

Light pollution is the brightening of the night sky due to artificial sources, such as street lights, illuminated billboards and exterior lights on buildings. More artificial light at night makes it more difficult to see the stars and other celestial objects.

“We’re having fewer and fewer places that are dark enough… to really meaningfully see the night sky,” Nolan said.

True dark sites are typically ranked 1 or 2 on the Bortle scale, a nine-level scale for measuring night sky brightness. Based on some light pollution maps, Illinois does not have a single “true” dark site.

Nolan wants people to understand that light pollution on Earth is controllable. There are simple steps that can be taken to put caps on light pollution: “literal, physical caps on street lights that massively reduce the amount of upward light pollution that we produce,” he said.

He urges the public to look out for local initiatives to reduce light pollution and remember their vote matters on such issues.

“I think that we’re really depriving future generations of — at least to me — one of the fundamental inspirational things about living on Earth: being able to look up and seeing the night sky,” Nolan said.