Abstract

Sandflies (Diptera; Psychodidae) are medical and veterinary vectors that transmit diverse parasitic, viral, and bacterial pathogens. Their identification has always been challenging, particularly at the specific and sub-specific levels, because it relies on examining minute and mostly internal structures. Here, to circumvent such limitations, we have evaluated the accuracy and reliability of Wing Interferential Patterns (WIPs) generated on the surface of sandfly wings in conjunction with deep learning (DL) procedures to assign specimens at various taxonomic levels. Our dataset proves that the method can accurately identify sandflies over other dipteran insects at the family, genus, subgenus, and species level with an accuracy higher than 77.0%, regardless of the taxonomic level challenged. This approach does not require inspection of internal organs to address identification, does not rely on identification keys, and can be implemented under field or near-field conditions, showing promise for sandfly pro-active and passive entomological surveys in an era of scarcity in medical entomologists.

Introduction

Sandfly insects belong to the order Diptera, family Psychodidae. They are medical and veterinary important vectors of diverse viral, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens. Leishmaniases, caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania (Trypanosomatida: Trypanosomatidae), occur in large areas, mainly the tropics and subtropics, recently emerging into new regions due to climatic and environmental changes1,2,3,4. Leishmanioses are among most important Neglected Tropical diseases with their endemic distribution including more than 98 countries and territories where over 350 million people are at risk for infection and 12 million individuals affected annually. Moreover, canine leishmaniasis is a severe veterinary problem, with an estimated 2.5 million dogs infected only in the Mediterranean basin5. Besides being principal vectors of most Leishmania species, phlebotomine sandflies are also involved in the transmission of viruses belonging to Rhabdoviridae, Flaviviridae, Reoviridae, Peribunyaviridae, and Phenuiviridae families. Among these, Phenuiviridae (Bunyavirales), encompassing the Phlebovirus genus, is often identified in sandflies and threatens human health6,7. Among pathogenic bacteria trasmitted by sandflies, Bartonella bacilliformis, a causative agent of Carrión’s disease in rural Andean areas of Peru and Ecuador, shall be mentioned8.

Over 900 sandfly species are recognized and formally described from Old and New World1. As only some species have a vectorial capacity to contribute to parasite transmission (118 suspected and 47 proven vectors), from a perspective of medical entomology, it is of uppermost importance to accurately identify phlebotomine sandflies. Only species belonging to Phlebotomus in the Old World and in the New World, various genera, including Lutzomyia Migonemyia… in the New World, are regarded as proven vectors of human and veterinary pathogens. However, field and laboratory evidence supports some species of the Sergentomyia genus as potential vectors’ role in Leishmania and viruses’ transmission6,9,10.

Phlebotomine sandfly morphological identification has always been challenging, particularly at the specific and sub-specific levels, because of variations in criteria and methods, morphological similarities between species, the inadequacy of descriptions, and the massive increase in the number of sandfly species described. Besides these limitations, the need to examine internal structures (arrangements of aedeagi and appendages in males, morphology of spermathecae in females) or external structures prone to damage during trapping and sample handling (e.g., the structure of the male genitalia, wing venation, and antennal and the palpal formula) is time-consuming and puzzled species identification. In addition, it is devoted to a limited and currently decreasing number of skilled specialists. Therefore, implementing new, affordable, and easy-to-handle methods for accurate sandfly identification is crucial from an entomological and medical survey perspective.

Wing Interference Patterns (WIPs) have received attention for their taxonomic potential11,12,13. The thin-film interference occurring on the wings’ transparent membrane allows the formation of a colored pattern. These WIPs significantly vary among specimens belonging to different species but moderately between specimens for the same species or between sexes. Unlike the angle-dependent iridescence effect of a flat film, the newton color series displayed is proportional to the thickness of the wing membrane at any given point, wing structures acting as diopters ensuring the WIPs appear essentially non-iridescent12. Deep learning (DL), a branch of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), has achieved outstanding results on several complex cognitive tasks, matching or beating those provided by human performance. It has proven helpful for tasks such as image and speech recognition, natural language processing, and object detection14. Recently, we have probed the capability of DL in classifying WIP pictures taken from wings of (Glossinidae Theobald, 1903)15 and (Culicidae Meigen 1818)16, two medically important dipteran families. Here, we investigate the reliability and specificity of such a method for Old World Phlebotominae species diagnostic and provide some clues that WIPs can be detected on New World species and, therefore, would be amenable.

Material and methods

Specimen selection and storage

The database of WIP from Psychodidae insects, comprising 1673 pictures, gathers samples belonging to the Phlebotominae family in the majority from well-established laboratory breeds, limiting potential intrapopulation WIP variations, but also from specimens collected in natura whose identification was performed at the time of their catch with available regional identification keys. Laboratory-reared representatives were provided using a standard method of sand fly breeding17. The description of the samples used in this study is given in Table 1.

Image acquisition and database construction

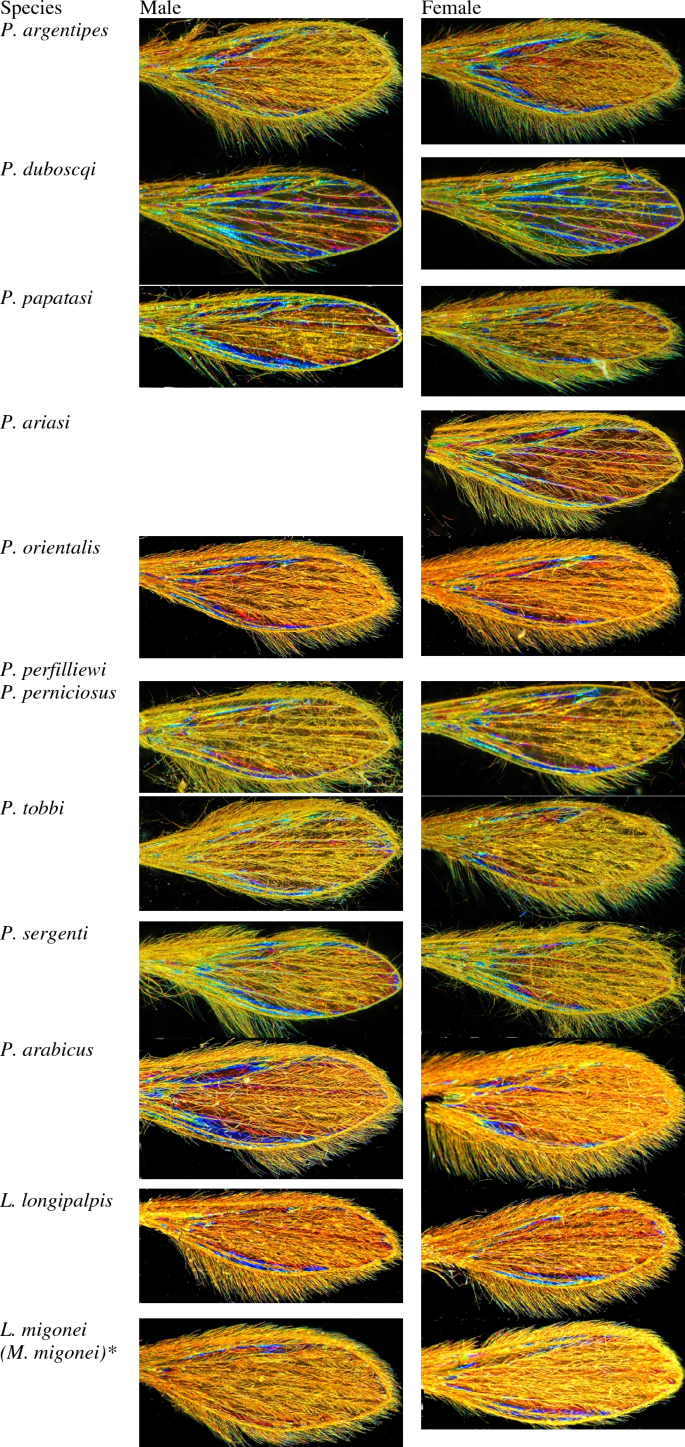

The protocol used to capture sandfly WIPs was as already described for Glossina sp. WIPs acquisition15. Briefly, dissected wings were deposited on a glass slide and covered by a small cover slide. A Keyence™ VHX 1000 microscope, using the VH-Z20r camera, and a Keyence VH K20 adapter set for an illumination incidence of 10° were used. All pictures were enlarged to a maximal occupancy, and the High Dynamic Range (HDR) function was used for all photos. Shots were then filled in a database with their taxonomic information, sex, date of capture, country of collection, and name of the entomologist that has undergone morphological identification. All pictures were filled in the database. See Fig. 1 for an example of images gathered during the study.

Examples of pictures included in the training dataset. *According to the updated taxonomy of New World sandflies.

Collected dataset, image pre-processing, and dataset splitting for training/learning and validation.

The Phlebotomine dataset includes 1673 pictures of 17 sandfly species18. Underrepresented sandfly species (less than ten samples/pictures) were discarded from the training dataset to prevent overfitting. Processed images were then resized to 256 width and 116 height pixels, and pixel values were normalized within the (0,1) range. The dataset was prepared for k-fold cross-validation, with k = 5, shuffled randomly, and partitioned into k equal-size subsets having a similar class distribution. A separately learned classifier was evaluated for each subgroup using kth of the whole dataset for validation and the remaining k-1 as training data (see Fig. 2A for illustration).

(A) Schematic representation of the dataset splitting for learning (red) and testing (orange), (B) representation of the pipeline process developed using the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) approach. Two steps predict the class of a given Phlebotominae WIP images: extracting hierarchical features (Convolutional layer) and classifying these features (Fully-connected layer and softmax layer). These feature maps are used for visualization by weighting them with channel-wise averaged gradients from Cannet et al.15.

This strategy allowed measuring the mean accuracy of the five distinct classifiers. Among all existing machine learning methods, Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and their different architectures have shown in the last decade to be the most adapted for image classification. A pipeline overview of the complete training procedure using CNN is shown in Fig. 2B.

Training of the neural network (CNN)

CNN architecture of MobileNet19, ResNet20, and YOLOv221 were deemed for automatically classifying sandfly specimens with the dataset. Compared to classic Deep Learning, ours is more compact to cope with the specificity of our dataset in terms of size; therefore, thinner image recognition and classification architecture were developed to consider its reduced size. Inspired by MobileNet, the first takes advantage of depth-wise convolution19, with only one depth-wise convolution per layer of the CNN architecture that reduces the complexity and number of features extracted. A batch normalization was set to speed up and stabilize the training process22. In addition to this first compact CNN architecture, two interconnected layers like VGG23 for YOLOv2 were applied with a DarkNet-1921 architecture with 1 or 2 scales less than the original network. For clarity, we called them DarkNet-9 (8 convolution layers and one classification layer) and DarkNet-14 (13 convolution layers and one classification layer). We also reproduced the ResNet18 architecture from He and collaborator20 and trained it from random initialization. Even if this architecture seems too “deep” (may lead to overfitting) compared to our other architectures, the intrinsic properties of ResNet18, residual connections, allow convergence of the training procedure. We used a standard approach (shallow approach) based on extracting SURF descriptors (an efficient implementation of the classic SIFT descriptors), a Bag of Features (BoF) representation using a 4000 codewords dictionary, and an SVM with a standard polynomial kernel similar to it was proposed in Sereno et al.24.

Results and discussion

To thoroughly investigate the proposed method’s accuracy, we test its capability to correctly assign sandfly specimens at various taxonomic levels: subfamily, genus and subgenus, and species.

Test for accuracy at the family/subfamily taxonomic level

The accuracy of the classifier was tested at various taxonomic levels ranging from the family (Psychodidae) to the genera (Phlebotomus, Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia & Migonemyia, if taking into account revised taxonomy25,26), Sergentomyia) and the species level (12). The Psychodidae family encompasses about 2600 species; however, only specimens belonging to the Phlebotominae subfamily are included in the dataset due to their medical importance as pathogen vectors. We first explored the training classifier accuracy on the Phlebotomine dataset and other non-Psychodidae specimens from Calliphoridae, Culicidae, Glossinidae, Muscidae, and Tabanidae datasets18. We trained the CNN on such a combination to improve the model’s accuracy. The dataset was filled with 1673 pictures of Phlebotomine WIPs. Still, five species were unsatisfactorily covered in terms of WIP pictures and were discarded from the training dataset of the Phlebotomine subset. Using this pictures-set, we ascertain the accuracy of the process to discriminate the Psychodidae family from other non-Psychodidae. From our dataset and method, the automatic classification process accuracy is an astonishing 99.8% (Table 2). Knowing that the wing size doesn’t belong to the descriptor selected during the training process, our classification accuracy would rely on other descriptors more specific to the WIPs.

Test for accuracy at the genus taxonomic level

Sandfly taxonomy has complex and still ongoing evolution. A conservative and simplified approach recognizes six main genera: three in the Old World (Phlebotomus, Sergentomyia, and Chinius) and three in the New World (Lutzomyia, Brumptomyia, and Warileya)1. Although a revision of the New World genera was recently proposed1,26, in this study, since we refer to this conservative taxonomy27, we still added the information dealing with the revision of the New World sandfly taxonomy to highlight changes. Therefore, L. migonei specimens are gathered with those of L. longipalpis in the analysis and the accuracy computation. We have also focused on the genera that harbor proven or suspected vectors and thus are most relevant for human or veterinary medicine. Our dataset contains pictures documenting three genera if we refer to Akhoundi and Coll1 (Phlebotomus, Lutzomyia, and Sergentomyia), and four if we refer to the revised taxonomy25,26, clearly more samples are required to address this question on New World sandfly fauna. At the genus level, our classification accuracy was always > 90% (Table 3).

Test for accuracy at the subgenus taxonomic level

To further investigate the taxonomic congruence of our methodology with the already proposed one, we assess its classification reliability at the subgenus level. At the generic level, the subgenera of sandflies have been intensively studied over many decades, with taxonomists providing varying views about their number and designation. The genus Phlebotomus currently encompasses 13 subgenera. For the genus Sergentomyia, ten subgenera are proposed. The Chinus genus is not further divided into subgenera. The taxonomic subdivisions in Neotropical Phlebotominae are rather complex and remain debatable26,28. A checklist of American sandflies is available25. We use the classification provided by Akhoundi et al.1. Our dataset does not fully cover the biodiversity of sandflies, particularly for New World sandfly species, at the subgeneric level; however, we provide data on four subgenera of the genus Phlebotomus, namely Adlerius, Larroussius, Paraphlebotomus and Phlebotomus, that in total harbor 30 species proven or suspected as vectors or many human-infecting Leishmania4. At the subgenus level, the classification accuracy computed remains high, consistently above 80% (Table 4). Higher confusion occurs between the Adlerius and Laroussius subgenera, which are regarded as phylogenetically close, than the Sergentomyia and New World (Lutzomyia and Migonemyia) ones.

Test for automatic classification of the 12 sandfly species filled in the dataset

At the species level, our data set is filled with pictures of 17 species, but only 12 provided enough images to encompass a training process. Even if limited in terms of species richness, considering the vast number of sandfly species described (900–1000), our dataset is composed of primary proven vectors of pathogens causing cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in the New and Old World, which highlighted the interest for medical entomology purposes. Among the 12 species in the dataset that have undergone a learning process, the best accuracy score was for P. papatasi (100%), the proven vector of L. major (an agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis). The lower recorded accuracy score (77.8%) is computed for P. perniciosus, a proven vector of L. infantum (an agent of visceral leishmaniasis). The overall accuracy scores remain astonishing and are always higher than 77% for all the species filled in the database (Table 5). The exactness of the method to assign sandfly species must now be probed on a larger in natura collected sandfly sample covering a wider geographic area, including New World species. In addition, with the methods proposed, WIPs variation at the populational level can be investigated with a proper sampling strategy.

Morphological species identification remains a golden standard in sandfly taxonomy; however, it is prone to various limitations, including compromised state of decisive structures in the field-collected specimens, intraspecific variability among populations, laborious sample preparation and declining entomological expertise among taxonomists. Hence, alternative molecular approaches are gradually applied, namely DNA sequencing (DNA barcoding)29 or MALDI-TOF protein profiling30,31,32,33,34,35. These methods, however, also have their limitations. It was demonstrated that reference DNA sequences for sandflies currently cover less than 50% of the subfamily species diversity, and, depending on the sandfly group or genus, different markers rather than a universal set are applied26,36. Moreover, despite increasing affordability and decreasing costs per analysis, sequencing is still not always available in some endemic countries and requires considerable expertise. MALDI-TOF protein profiling, a mass spectrometry method, provides a time- and cost-effective alternative as the sample preparation is quick and cheap. However, the required machinery may be prohibitively expensive and not always readily available to medical entomologists. So far, only in-house databases of sandfly reference protein spectra have been established, further limiting the applications of this approach. In addition, the interoperability of MALDI-TOF requires a standardized procedure in the conservation of samples, the choice of the adult specimen body part or even the trapping method37, and the standardization of procedures for preparation and reproducibility between instruments and homemade databases is desirable33. Hence, an alternative method for species identification of adult sandflies performed under conditions that do not allow costly and highly sophisticated infrastructures is highly desirable.

The application of Deep learning leads to robust results in terms of classification performance. The proposed method has the potential to be used in real-life scenarios since the proposed architecture ends up with a good compromise compared to other methodologies reviewed in Cannet et al.15. Future development and technical implementation of this methodology include strengthening the database in terms of Phlebotomine species and population representation, the use of GANs (Generative adversarial network) allowing to fill up the database with new species, even with a low number of representatives. From an application point of view, previous works15,16,24 and this study add evidence to the generic potential of the method for dipteran insect identification. Implementing a SaaS platform would offer a complete service for remotely localized computers with an internet connection.

Conclusions

During field entomological surveys, most routine sandfly identification involves diagnostic criteria, requiring dissections and slide-mounting to examine internal organs. An alternative morphological approach that surpasses the need for molecular analyses will be to develop computer vision relying on visual characters of taxonomic interest to assign taxon names. Therefore, using WIPs as a valuable taxonomic marker in conjunction with DL will help address challenges concerning sandfly identification. Further analyses of field-caught specimens of a more significant part of sandfly biodiversity will be needed to increase the method’s accuracy.

Data availability

The source code is publicly available on GitHub, with a direct URL: https://github.com/marcensea/diptera-wips.git.

Code availability

Dataset is available with a direct URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22083050.v4.

References

-

Akhoundi, M. et al. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of leishmania parasites and sandflies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004349–e0004349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004349 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Sereno, D. Leishmania (Mundinia) spp.: from description to emergence as new human and animal Leishmania pathogens. New Microbes New Infect. 100540–100540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2019.100540 (2019).

-

Kholoud, K., Sereno, D., Lahouari, B., El Hidan, M. & Souad, B. Management of Leishmaniases in the Era of Climate Change in Morocco. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1542–1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071542 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Kholoud, K., Bounoua, L., Sereno, D., El Hidan, M. & Messouli, M. Emerging and re-emerging leishmaniases in the mediterranean area: What can be learned from a retrospective review analysis of the situation in Morocco during 1990 to 2010? Microorganisms 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8101511 (2020).

-

Alvar, J. et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS ONE 7, e35671–e35671. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035671 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Jancarova, M., Polanska, N., Volf, P. & Dvorak, V. The role of sand flies as vectors of viruses other than phleboviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 104. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001837 (2023).

-

Maroli, M., Feliciangeli, M. D., Bichaud, L., Charrel, R. N. & Gradoni, L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med. Vet. Entomol. 27, 123–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Ruiz, J. JMM Profile: Bartonella bacilliformis: A forgotten killer. J. Med. Microbiol. 71. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001614 (2022).

-

Maia, C. & Depaquit, J. Can Sergentomyia (Diptera, Psychodidae) play a role in the transmission of mammal-infecting Leishmania?. Parasite 23, 55. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2016062 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Ticha, L. et al. Experimental feeding of Sergentomyia minuta on reptiles and mammals: Comparison with Phlebotomus papatasi. Parasites Vectors 16, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05758-5 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Buffington, L. M. & Sandler, J. R. The occurrence and phylogenetic implications of wing interference patterns in Cynipoidea (Insecta : Hymenoptera). Invertebr. Syst. 25, 586–597 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Shevtsova, E., Hansson, C., Janzen, D. H. & Kjærandsen, J. Stable structural color patterns displayed on transparent insect wings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 668–673. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017393108 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Simon, E. Preliminary study of wing interference patterns (WIPs) in some species of soft scale (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Coccoidea, Coccidae). Zookeys, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.319.4219 (2013).

-

Janiesch, C., Zschech, P. & Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 31, 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-021-00475-2 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Cannet, A. et al. Wing interferential patterns (WIPs) and machine learning, a step toward automatized tsetse (Glossina spp.) identification. Sci. Rep. 12, 20086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24522-w (2022).

-

Cannet, A. et al. Deep learning and wing interferential patterns identify Anopheles species and discriminate amongst Gambiae complex species. Sci. Rep. 13, 13895. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41114-4 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Lawyer, P., Killick-Kendrick, M., Rowland, T., Rowton, E. & Volf, P. Laboratory colonization and mass rearing of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae). Parasite 24, 42. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2017041 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Sereno, D. et al. Listing and pictures of Diptera WIPs. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22083050.v1 (2023).

-

Howard, A. G. et al. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:abs/1704.04861 (2017).

-

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

-

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 6517–6525 (2017).

-

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. arXiv:abs/1502.03167 (2015).

-

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. CoRR abs/1409.1556 (2015).

-

Sereno, D., Cannet, A., Akhoundi, M., Romain, O. & Histace, A. Système et procédé d’identification automatisée de diptères hématophages. France PCT/FR15/000229. patent (2015).

-

Shimabukuro, P. H. F., de Andrade, A. J. & Galati, E. A. B. Checklist of American sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae): genera, species, and their distribution. Zookeys 1, 67–106. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.660.10508 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Galati, E. A. B. & Rodrigues, B. L. A review of historical phlebotominae taxonomy (Diptera: Psychodidae). Neotrop. Entomol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-023-01030-8 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

WHO. Arboviruses and human disease. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 369, 1–84 (1967).

-

Rodrigues, B. L. & Galati, E. A. B. Molecular taxonomy of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) with emphasis on DNA barcoding: A review. Acta Trop. 238, 106778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106778 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Massey, A. L. et al. Invertebrates for vertebrate biodiversity monitoring: Comparisons using three insect taxa as iDNA samplers. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 962–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13525 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Lafri, I. et al. Identification of Algerian field-caught phlebotomine sand fly vectors by MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004351. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004351 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Dvorak, V. et al. Identification of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. Parasites Vectors 7, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-21 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Arfuso, F. et al. Identification of phlebotomine sand flies through MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and in-house reference database. Acta Tropica 194, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.03.015 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Mathis, A. et al. Identification of phlebotomine sand flies using one MALDI-TOF MS reference database and two mass spectrometer systems. Parasites Vectors 8, 266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0878-2 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Huguenin, A. et al. MALDI-TOF MS limits for the identification of mediterranean sandflies of the Subgenus Larroussius, with a special focus on the Phlebotomus perniciosus complex. Microorganisms 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10112135 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Chavy, A. et al. Identification of French Guiana sand flies using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with a new mass spectra library. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007031 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Depaquit, J. Molecular systematics applied to Phlebotomine sandflies: review and perspectives. Infect. Genet. Evol. 28, 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2014.10.027 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Halada, P. et al. Effect of trapping method on species identification of phlebotomine sandflies by MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling. Med. Vet. Entomol. 32, 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12305 (2018).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank Pr. P. Marty and P. Delaunay (CHU Nice) for gaining access to the microscopic facility of the CHU. Dr. D. Fontenille (UMR MIVEGEC, Montpellier, France) for his support and fruitfully scientific discussions on medical entomology aspects. Mr JP Commes, former CEO of 2CSI, for his enthusiasm and advice on the digital aspect of the project.

Funding

This work was partially supported by H2020 Research Infrastructures, grant Infravec2, no. 731060 and LeiSHield-MATI 778298 grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation De.S., A.C., M.A., A.H., C.S.C., O.R., M.S. Data acquisition De.S., A.C., M.S., A.H., Da.S. Database construction De.S., Da.S., A.H., P.J., M.S., O.R. Sample collection and arthropod management P.V., A.C., V.D., De.S. Project management De.S., A.H., C.S.C. Writing first draft A.H., De.S., A.C. Writing and editing De.S., A.C., M.A., C.S.C., A.H., P.V., V.D.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cannet, A., Simon-Chane, C., Histace, A. et al. Species identification of phlebotomine sandflies using deep learning and wing interferential pattern (WIP).

Sci Rep 13, 21389 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48685-2

-

Received: 21 June 2023

-

Accepted: 29 November 2023

-

Published: 04 December 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48685-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.