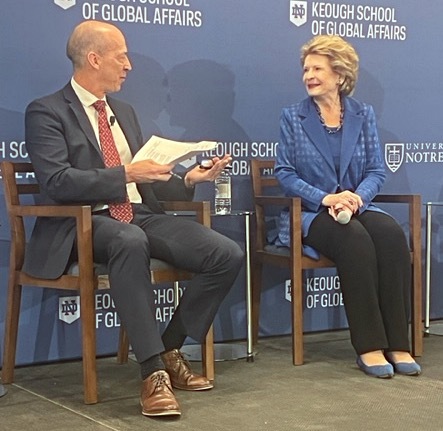

“We need a moonshot on research. … We need more resources than what we have in the farm bill,” Stabenow said at an event sponsored by the University of Notre Dame’s Keough School of Global Affairs. The event was titled “COP28: Agricultural Innovations to Address Climate Change and Food Security.”

Stabenow noted that Congress had “passed a bill to give substantial resources to the National Science Foundation but none of that seems to be going to agriculture.”

Saying she is “trying to figure out what we could do that would be something substantial,” she added, “we need to think broadly about research. The farm bill is one piece.”

She also pointed out that in the farm bill, “We operate on a baseline of funding. It does not accommodate what we need in terms of research.” She added that many agricultural research facilities are “old.”

Stabenow noted that there are several buckets of agricultural research within the farm bill, including specialty crop and organic research.

She pointed out that the 2014 farm bill created the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research to leverage public and private money to advance food and agricultural science.

(The extension of the 2018 farm bill through September 2024 passed last week in the continuing resolution to fund the government included $37 million for FFAR. In a press release issued Nov. 17, Sarah Moon Chapotin, the FFAR executive director said, “I am honored that congressional leaders value FFAR and are continuing to support FFAR’s bold science. In 2023, FFAR expects to award over $145 million, including over $60 million in public funds and an additional $85 million leveraged from partners.”)

Stabenow noted that times have changed since the days when other senators would not allow the use of the term “climate change” in the farm bill, meaning conservation programs addressing the topic had to be called “innovation conservation grants” and hearings had to be about “severe weather.”

The Growing Climate Solutions Act that Stabenow co-authored was the first to have the word “climate” in the title. That act is vital, she said, because it will allow the Agriculture Department to develop the standards for a carbon market.

“We want a carbon market that actually works,” she said, not “greenwashing, not pretend,” but one that will allow farmers to have an additional source of revenue.

Farmers have told her carbon markets are “the Wild West,” with people telling them they have a deal that doesn’t work.

Agricultural innovation has a history of rising to challenges starting with the Dust Bowl, she said, noting that the Senate Agriculture Committee held a hearing recently on the potential and problems associated with artificial intelligence in agriculture.

Stabenow noted that this is the sixth farm bill on which she has worked and the third time she has been in charge.

“It gets more challenging every time we are doing this. On every one, and this one especially, the climate crisis is a focus for me. We have made progress over and over again.”

Stabenow repeated previous statements that she is willing to move the $20 billion in climate-related conservation spending that is in the Inflation Reduction Act into the farm bill, but only if the money will still be spent on its stated purpose.

Some Republicans have proposed using that budget authority for commodity farm subsidies. If Congress raises the reference prices that trigger farm subsidy payments, more budget authority would be needed.

People say planting trees and cover crops and rotating crops are “too simple,” but if those practices were “done everywhere they would have a profound impact,” she said.

“We’ve got to lean in on methane and other greenhouse gases, lean in on methane digesters,” she added.

Globally, emissions cannot be addressed without including agriculture and forestry, she said.

Stabenow also said she was glad that the COP28 meeting will place an emphasis on agriculture for the first time.

Paul Winters, a professor of global affairs at Notre Dame, said it is “a big step” for the UN to include agriculture in the COP28 program, and that he hopes agriculture and food will be incorporated into countries’ commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Winters noted that he had a recent conversation with an official from Lavazza, the Italian coffee company, about the impact of global warming on coffee production. The official said the company is counting on Brazil, which produces about a third of the world’s coffee, to be innovative, but Winters said it’s unclear what this means for smaller coffee producers such as Uganda and Costa Rica.

On all the climate issues affecting agriculture, Winters said, “The only path I see is through innovation.”

The challenge, he added, is to limit greenhouse gas emissions and still produce enough food for the world’s growing population. A lot of research is taking place, but commercial incentives are insufficient and the projects are not “scaling,” he said.