- A new study from Indonesia’s Leuser forests challenges the traditional use of charismatic “umbrella species” like tigers and rhinos to represent ecosystem biodiversity.

- Researchers found that focusing on these well-known species neglects other important wildlife and may not accurately represent overall biodiversity.

- Instead, the study proposes a data-driven approach using camera-trap data to identify the most suitable umbrella species based on their association with higher levels of community occupancy and diversity.

- The study identified the sambar deer and Sunda clouded leopard as better umbrella species than tigers and rhinos in the Leuser Ecosystem, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive approach to wildlife conservation that includes multiple species, not just the most charismatic ones.

JAKARTA — In wildlife conservation management, the best species to focus on to maximize protection of a region’s biodiversity aren’t necessarily the most charismatic ones, a new study from Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem suggests.

Conservation managers have long prioritized the management of what are known as umbrella species, on the basis that protecting these high-profile species also protects the ecosystem in which they live. These species tend to be ones that roam wide and large areas, which for conservation management purposes makes them representative of other, lesser-known, species. As a result, these umbrella species usually get special attention from conservation managers, funders and authorities.

However, researchers from Indonesia and the U.K. have found that focusing on the usual charismatic species, like tigers and rhinos, leads to neglect of the needs of other wildlife. In a new paper published in Biological Conservation, they note that these non-flagship species might actually be better representatives of the broader biodiversity of a particular ecosystem than those considered the umbrella species.

“Our study proposes a new framework to identify the best umbrella species using camera trap data collected from the field and accounting for imperfect detection i.e. that species might be undetected during surveys but they are present,” study lead author Ardiantiono, a Ph.D. student at the School of Anthropology and Conservation at the University of Kent, U.K., told Mongabay in an email interview.

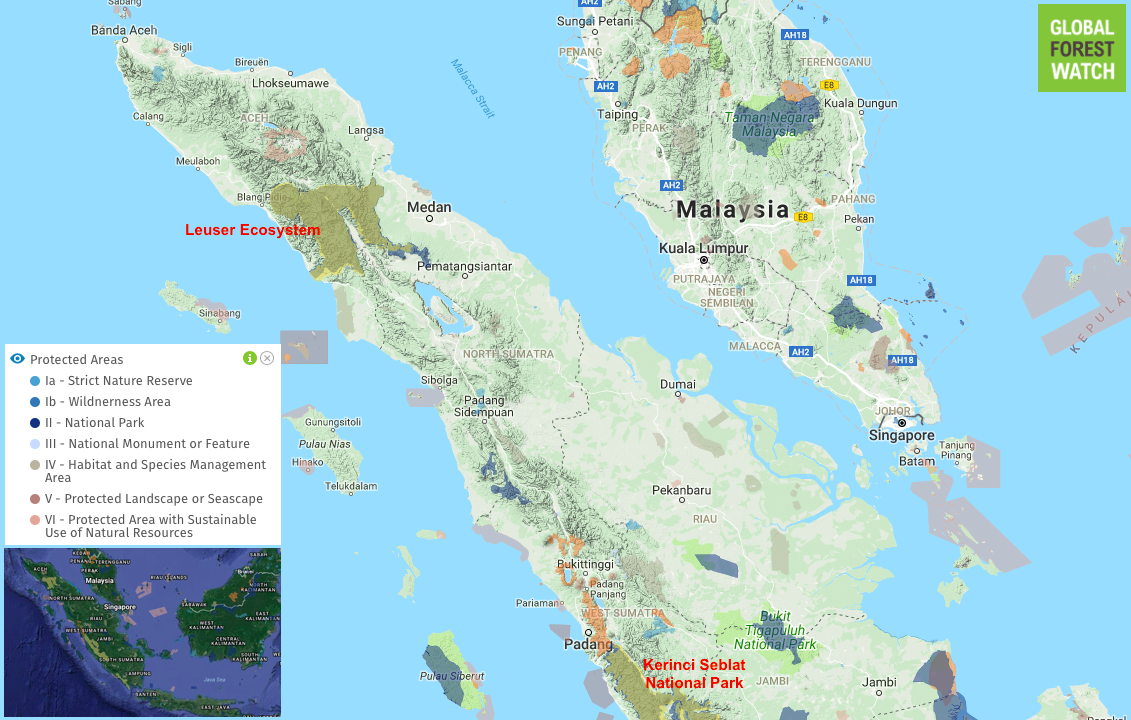

For their study, the researchers focused on the Leuser Ecosystem, the largest remaining intact swath of tropical rainforest in Sumatra, and the only place on Earth where tigers, rhinos, orangutans and elephants are found in the same habitat. Three-quarters of the ecosystem is protected to varying degrees, including a large chunk that falls within Gunung Leuser National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The remainder, however, has experienced encroachment from agricultural expansion, road development, and human settlements.

The researchers conducted camera-trap surveys from May 2016 until August 2017 and June 2017 to March 2018 to evaluate the “umbrella performance” of eight mammal species that could be considered umbrella species: the Sumatran hog badger (Arctonyx hoevenii), mountain serow (Capricornis sumatraensis), dhole (Cuon alpinus), Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatranus), sun bear (Helarctos malayanus), Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi), Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) and sambar deer (Rusa unicolor).

What they looked for in particular was occupancy data associated with each species, i.e. the richness of mammal diversity in areas that these candidate umbrella species occupied.

The findings showed that it was the mostly overlooked species that were associated with these higher levels of occupancy and diversity — animals like the sambar deer and clouded leopard. By contrast, the Sumatran tiger and rhino, by far the biggest beneficiaries of conservation attention and funding in Sumatra, were found to have the lowest levels.

Ardiantiono noted, however, that his team’s study was conducted in the relatively pristine forest of the Leuser Ecosystem; in other, more degraded or fragmented landscapes, tigers might be a better umbrella species.

The findings, nevertheless, make clear that “We should be monitoring several species together — not just the charismatic ones that attract conservation funding,” Ardiantiono said. “Considering this fleet approach will help Indonesia wildlife management to put more attention to the conservation of multiple species, including ones it already prioritized to protect and monitor.”

From 2017 to 2019, approximately $4.5 million was dedicated to conserving four charismatic large mammals — the Sumatran rhino, tiger, elephant and orangutan — in exchange for writing off some of Indonesia’s foreign debt. The figure exceeded the combined investment in landscape-focused conservation initiatives (approximately $3.3 million) for Sumatra as a whole.

Anna Nekaris, an anthropology and conservation professor at Oxford Brookes University who has long studied small primates in Indonesia, said the new paper demonstrates the importance of a data-driven approach when selecting umbrella candidates and that “being large and charismatic is no longer the best solution.”

“I feel that special attention needs to be given to this evidence-based approach since it is easy to assume that a large charismatic species automatically covers the habitats and micro ecosystems of smaller taxa,” said Nekaris, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Smaller taxa, including amphibians and invertebrates, are often completely overlooked in these studies, and it could be that multiple umbrellas are needed too (for example most of these species in this study are terrestrial),” she added.

Diah Fitri Ekarini, biodiversity conservation coordinator at the NGO Konservasi Indonesia, the local affiliate of Conservation International, said the study was “intriguing” because it offered an analytical framework for evaluating the performance of umbrella species by looking at the occupancy patterns of mammal communities that fall under this umbrella.

She said the methodology could assist conservation managers and authorities in selecting more suitable umbrella species candidates for a given landscape, and enable more targeted and comprehensive conservation efforts within the landscape.

“Increased public understanding and awareness of this concept will also broaden opportunities for public participation in conservation efforts,” said Diah, who wasn’t involved in the study. “It is hoped that the increased public understanding of this concept can positively impact conservation efforts by fostering more targeted approaches.”

All those interviewed agrees on the point that conservation managers and authorities must validate a species’ performance as an umbrella species before focusing their efforts and funding on it as a representative of the broader biodiversity of a landscape. Ardiantiono said the camera-trap data his team used came at little additional cost, as the animals were detected as bycatch for campaigns focused on tigers and rhinos.

“There is no species that can fully represent other biodiversity in an ecosystem,” Ardiantiono said. “Unfortunately this important message is often lost as we tend to strive for simplicity in conservation messaging — especially with the wider public who are an important source of conservation funding.”

Basten Gokkon is a senior staff writer for Indonesia at Mongabay. Find him on 𝕏 @bgokkon.

See related story:

Can we save the Leuser Ecosystem? | Chasing Deforestation

Citations:

Ardiantiono, Deere, N. J., Ramadiyanta, E., Sibarani, M. C., Hadi, A. N., Andayani, N., … Struebig, M. J. (2024). Selecting umbrella species as mammal biodiversity indicators in tropical forest. Biological Conservation, 292. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110511

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.