Czinger is at the forefront of harnessing AI technology and currently developing its Divergent Adaptive Production System (DAPS) for vehicle manufacturing. The company is a subsidiary of California-based Divergent 3D, and its 21C (see Source material, APTI, June 2022, p4) makes extensive use of metal AM throughout its structure and powertrain.

“The idea of doing the gearbox case has been on the agenda for about four years,” reveals Czinger chief engineer Ewan Baldry. In the early days of the project, though theoretically feasible, the footprint of the metal AM machines then in use couldn’t accommodate a complete transmission casing. However, Baldry had confidence in the developments Divergent had underway: “We knew on the roadmap that we would be going to machines that would be capable of doing something for this kind of size.”

Despite the company’s extensive expertise and the success of the 21C to date, production of a component as complex as a transmission casing, with the associated critical tolerances and durability requirements, was not to be taken lightly. “It was a pretty ballsy decision because obviously, at some point, you’re committing to printing it,” says Baldry. “That means you’re committing to design it in a way that fundamentally probably isn’t fit for casting. If it didn’t work out, then it would be a massive U-turn, a huge delay to the program.”

Partners

Czinger is not a transmission manufacturer, hence its collaboration with Xtrac, a UK-based motorsport and high-performance automotive gearbox specialist. Xtrac would handle the nitty-gritty of the transmission internals while Czinger focused its efforts on producing the generatively designed and 3D-printed casing.

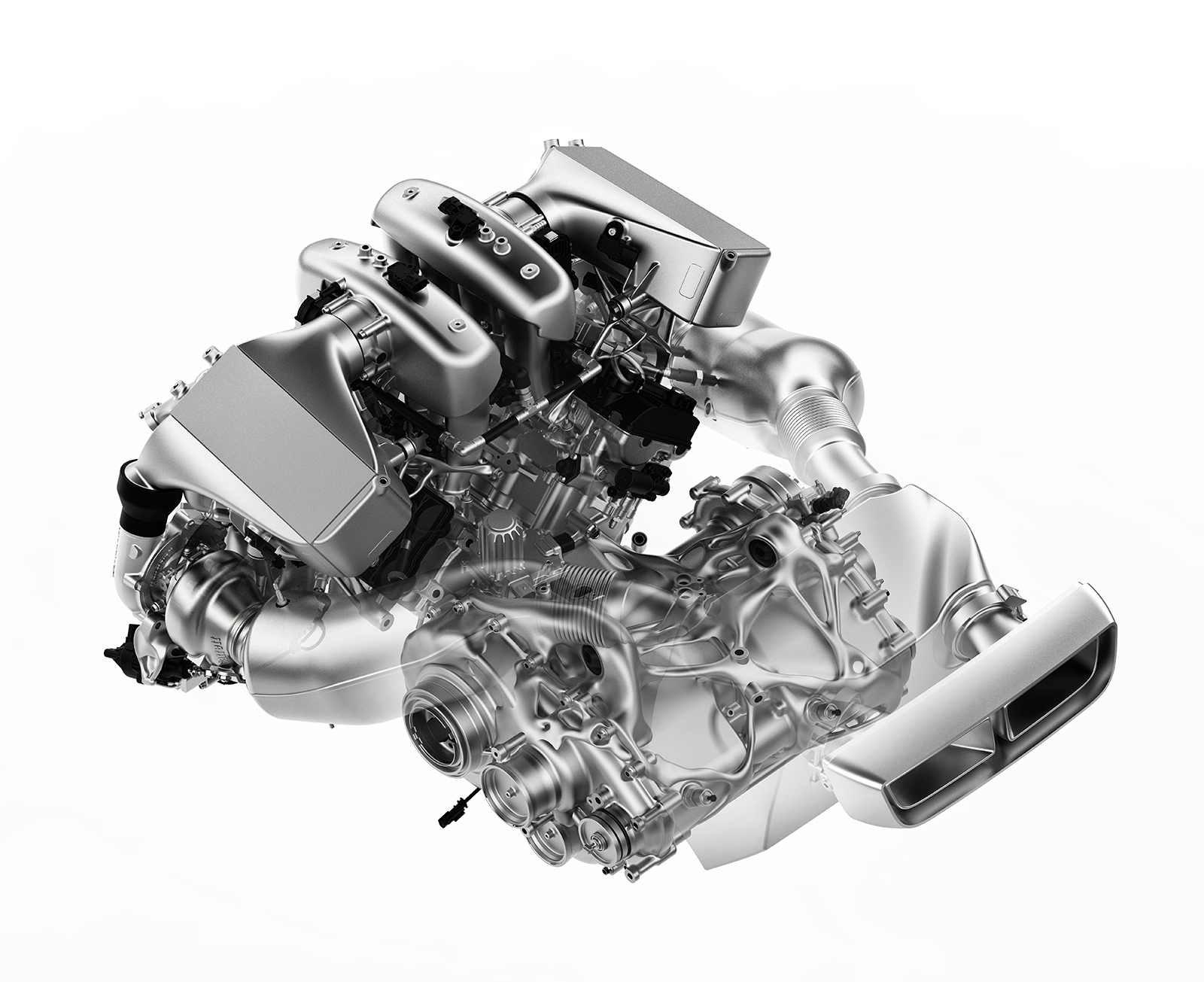

The 21C’s transmission is an automated, 7-speed semi-sequential unit with a 48V, electrically actuated twin-barrel shift system. According to both Czinger and development partner Xtrac, this combination has created the fastest automated single-clutch synchromesh gearbox in existence. As Xtrac CEO Adrian Moore explains, “All the parts are optimized for this particular car. We work with a synchromesh provider on custom-designed and specified synchronizers for this particular gearbox. The TCU (transmission control unit) is an Xtrac unit, along with the clutch actuator and diff actuator, delivered as an entire turnkey package.”

Commenting on the benefits of working with a hybrid system, with the option of 48V power, he adds, “It gives you more flexibility with the size of the [shift]actuator and, arguably, the response time and power of the actuator as well. A synchromesh gearbox with a barrel actuation is quite unusual, but it gives you a lot of flexibility in terms of gear change control.”

Divergent’s raison d’être is to advance the capabilities of AM, and it is undoubtedly ahead of the curve relative to the mainstream automotive industry. Many suppliers will have dabbled in the technology but few are fully invested in metal AM. Baldry suggests they may be unaware of what is possible, creating a degree of reticence when taking on groundbreaking applications such as a gearbox. His response to such hesitancy is, “Let us work together and show that it’s doable.”

To confirm the feasibility of printing an entire casing with the same or better properties than a cast production, Xtrac sent Czinger the CAD data for an existing gearbox, which the OEM printed and returned for final machining. It passed Xtrac’s durability tests with flying colors.

From there on it was a case of honing a design that incorporated the functionality and refinement expected of a hypercar while harnessing the flexibility provided by AM. Baldry explains, “The process for DAPS sees us create a ‘design volume’. The design volume is effectively a ‘blob’ of material in the CAD environment, which is us telling the optimization software, ‘You can put material any way you like here’. We also define the non-design features, typically fixing points, interfaces with mating components, etc, that we tell the software it can’t play around with. Once those areas are defined, then Mike [Bolton, senior vehicle integration engineer at Czinger] and the Divergent team run the optimizer to generate these structurally optimized shapes.”

Tailoring the optimization techniques to a gearbox casing entailed a constant exchange of information between Xtrac and Czinger. For example, explains Bolton, “We would advise on how to design elements to make them more printable, while they would provide data on elements such as bearing locations, loads, etc, but also the minimum surface of the shrink-wrapped casing to make it oil-tight.”

That the casing needs to be oil-tight may seem obvious but this requirement had to be expressly added as a parameter, otherwise Divergent’s optimization software would only consider structural requirements. “If you look at the structural parts across the car, they have holes everywhere. If we just deployed DAPS as normal, you would have a case that couldn’t hold oil,” highlights Bolton. “It was a very interesting relationship [with Xtrac]with lots of back and forth to shape the CAD. And I think one of the biggest challenges was how to manage the data and knowledge transfer between the two of us.”

Performance and refinement

Printing compared to casting gives greater design freedom, allowing for geometries that would previously have been hard, if not impossible, to create. For example, draft angles are not needed, and overhanging features and varying wall thicknesses can be incorporated.

Despite the motorsport background of many of the team members and the clear performance intent of the car, it was decided not to use the transmission as a stressed chassis part because the impact on NVH would have been unacceptable. However, the stiffness and strength of the casing was still of utmost importance, for example, the dynamic stiffness of the casing under load affects its installation in the vehicle and the design and operation of the gears within. Baldry explains, “Our optimization engine allows us to use dynamic stiffness as one of the requirements. If you look at the other structures on the car, internally there are lots of weird and wonderful geometries that are driven by this dynamic stiffness requirement.”

Any displacement of the shafts within the casing under load has an impact on how the gears mesh. Bolton recalls, “The dynamic stiffness plays a role in the way the gears are cut. The involute profiles and microgeometries used account for any variation in the casing stiffness. Usually [with a cast casing], the stiffness is just what it is, and you need to compensate for it in the gear geometry. Whereas we were able to say, ‘What gear geometry would you like? We’ll target the stiffness to match that’.”

One of AM’s most appealing party tricks is the ability to incorporate internal geometries within solid parts that cannot be created using traditional manufacturing techniques. For example, the 21C transmission features a sump-based oil system that relies on a pair of pumps to keep the transmission lubricated. “The pump manifold is manufactured with all of the internal passageways already incorporated,” says Bolton. “There is no need for machining and they can take crazy routes that perfectly match the flow rates and pressure drop we need. They even run following the curved surface of the casing, rather than having to take straight lines. We have also printed in all the oil galleries throughout the main case.”

Returning to the topic of NVH, Bolton says that with a variety of thin wall features within the case, there was potential for resonances to occur, particularly in the integrated oil tank, which has a 2mm wall thickness. “What we did there is add a Voroni lattice pattern to stiffen those walls up, otherwise they would have definitely resonated,” he explains.

Iteration

Castings such as transmission casings are long lead time parts, and every detail needs to be baked in before committing to pattern making and production. Not so with AM, where it is possible to make design changes on the fly, from print to print. At the time of writing, Czinger had printed three iterations of the casing. “Each version has introduced further complexity and further integration into the system,” explains Bolton, suggesting that this approach needs some adaptation for engineers schooled in more traditional approaches. “That whole thought process was quite new to Xtrac, being able to think that we don’t have to be finished, we can start learning things and start testing things, making improvements as we go.”

A great illustration of this flexibility is the integrated oil tank. As testing of the initial transmission was underway, it was decided that the capacity of this tank needed to be increased. With a cast part, this would have required a complete retooling; instead, it was simply incorporated in the next print. “That’s a discovery that we only recently made and just in that area, we’ve saved a fortune in outlay and a lot of time. If it was cast, we just probably wouldn’t have been able to make that change,” stresses Bolton.

Mainstream implications

The 21C might be a bespoke hypercar, accessible only to a select few, but it is still fulfilling its role as a proving ground for Divergent’s technology. With an aim of bringing AM into mainstream automotive manufacturing, being able to print a fully functional transmission casing is a statement of intent. Not only that, development of the transmission has gone hand in hand with improving Divergent’s processes.

The company develops its own powder stock materials in-house. For the transmission casing, an aluminum-based alloy with properties comparable to L169, a common casting alloy used in high-performance gearboxes, was employed. “We’re already exceeding mechanical properties of typical cast materials,” observes Baldry. “And month by month, we’re refining those recipes to give us alloys that are really pushing out the envelopes of performance. Not just yield strength and UTS but also achieving high elongations where we need them.” Xtrac’s Moore reinforces just how impressive the material performance is: “3D printing aluminum is old hat really, but 3D printing aluminum that has this strength, this ductility, is something very different.”

The focus is not only on ensuring that the base stock has the required mechanical properties. “A further driving force is the productivity of the material,” adds Bolton. “There are materials out there that can achieve the same sorts of mechanical properties but you can’t print them fast and they are not commercially viable. So one of the biggest challenges, which Divergent is meeting, is that you have to be able to print fast and print accurately.”  The gains made in this area over the development of the transmission are impressive.

The gains made in this area over the development of the transmission are impressive.

Though the company is unwilling to divulge explicit details, refinements made to the printing process saw production time cut by almost a factor of 10. And it is not only the printing process that is being optimized ready for widespread industry adoption – every aspect of manufacture, from design to post-print heat treating, is under scrutiny.

“There are people here who are purely focused on the printing and increasing the print rates,” says Baldry. “But there are equal, if not more, looking at the pre-processing. How do we design things better, make them faster and quicker to print and to nest more tightly in a print volume? And then we’ve got people on the other side who are looking at all of the post-processing, which, to be honest, is still fairly manual [and]labor-intensive but won’t be for long.”

The 21C transmission is undoubtedly an impressive and effective creation. Not only has it proved the feasibility of AM production as an alternative to casting but it soundly outperforms a traditional cast unit in terms of torque capacity to weight. The unit is also far from the final iteration. Baldry and his team have a variety of tricks up their sleeves for future iterations, incorporating ever more functionality and integration into the design. There is also the matter of time-to-market, as Chris Wright, head of powertrain performance at Czinger, concludes: “From a pure performance point of view, there’s a big benefit. But just in terms of getting this car to market in the short amount of time available, we couldn’t have done it the casting way.