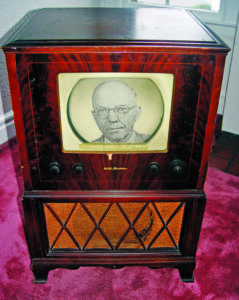

John Rooney on a 1949 television set.

Video is everywhere.

Today, whether people prefer TikTok, YouTube, Apple TV, Pluto TV, Prime Video, Netflix or some other service, they can view an endless steam of images anywhere at any time on their phones or tablets. News, sports, footage of cats and epic fails, new and old television series and movies are all available in large amounts.

But 75 years ago, a small, grainy, black and white image of a St. Louis basketball game was a big deal.

TV was the future and it had arrived in Robinson.

Coming attractions

A half-page advertisement in a late March 1949 issue of the Daily News — its first promoting television sets — was the offical welcome mat.

The ad, for the Rooney Electric Store in the Otey Building on South Cross, was placed by proprietor John Rooney, who clearly was eager to sell Robinson residents on the idea of purchasing a TV.

Rooney, 48, was so supportive of the new medium he installed two “receivers” in his home at 601 E. Chestnut. For 30 days, he and his family kept a log of their reception to “determine what efficiency Robinson people might expect from television sets in their homes.”

The Rooneys viewed “perfect pictures” on their TVs on seven nights and “fair pictures” on six more. The image was only fair on four nights and poor on six others. No image was available on seven nights, which he explained was because reception was impossible thanks to weather that was “very unsettled.”

“We might say that our log of our first month of reception is frankly better than we expected it to be,” Rooney said in the ad. “We think that with the summer months ahead, our reception will show quite an improvement.”

He confessed he did not expect to equal reception in the cities “where they have an average of five nights out of the week of good reception,” but with more stations expected to go on the air soon, he was sure Robinson would come close to it.

Rooney made no mention of what he watched, but he did say his family tuned in to all the stations available in the region.

“In this area there are stations in St. Louis and Louisville broadcasting in channel number five, in Cincinnati on channel four and Chicago on channels five, seven and nine. We have had good pictures and good sound from all four of these cities,” Rooney wrote.

At one time, however, the family picked up the sound from Louisville and images from St. Louis on the same channel.

“That’s not good,” he explained.

Signing on

The nearest station was about 150 miles away. “In order to get even this reception, it was necessary for us to have our antenna or tower extended to a height of 87 feet,” Rooney admitted. “It is possible for us to raise this tower to 110 feet.”

Height was essential to reception. “Television rays are broadcast in a straight line while the ordinary radio broadcast beame follow the curvature of the earth,” Rooney told readers.

“As the Good Lord has built this earth round, it has a curvature of about eight inches per mile which means that if we are to receive television in Robinson from such cities as St. Louis, Chicago, Louisville and Cincinnati, we must have our aerials at least 75 feet high.”

Stations, he was certain, would be more plentiful nationally in the next five years. “But as the present cost of building stations runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars, we believe that it will be sometime before Robinson has one in a radius of 50 or 60 miles.”

Cost wasn’t the only factor. In 1948, it became clear that overlapping signals from local stations were causing chaos. The Federal Communications Commission instituted a freeze on new station licenses until the overlap and other regulatory issues were cleared up. Expected to last a few months, the freeze was not lifted until April 1952.

The overlapping stations explains the night Rooney received sights and sounds from different cities on the same channel. Two of the stations his family picked up were KSD-TV and WAVE-TV, the only stations in St. Louis and Louiville, Ky., at the time. Both broadcast on channel 5. WAVE eventually moved to channel 3 because of interference created when WLWT in Cincinnati — another station the Rooney’s watched — jumped from channel 4 to channel 5.

The Chicago channel 5 — which apparently caused no problems here — was WNBQ. The other Windy City stations the Rooneys picked up were WGN and WENR, today WLS.

Rooney cited trade journals reporting Bloomington, Ind., and Indianapolis were expected to have stations in operation by May.

“Considering that these two points will be much nearer to Robinson and the fact that reception should improve with the coming of spring as well as the fact that our ‘know how’ is improving with the experience we are getting, we expect our next report to you to be more favorable.”

WFBM-TV’s first trial broadcast had taken place a week earlier from an Indianapolis athletic club.

Airing on channel 6, the station signed on May 30, but WTTV, which broadcast out of both Indy and Bloomington, didn’t make it on air until November. WUTV, an Indy station planned for channel 3, never made it to air.

Both WFBM and WTTV were originally NBC affiliates that aired ABC programs part time. WTTV would later be an independent station for decades, generating its own programming featuring the likes of Cowboy Bob and horror host Sammy Terry.

Originally, WTTV aired on channel 10. It switched to channel 4 in 1954, a few months before Terre Haute’s first station, WTHI, took over channel 10.

In 1949, television was broadcast on VHF (very high frequency) channels 2 to 13. Rooney included channel 1 in a list of broadcast channels, apparently not realizing the FCC had reserved it for public safety and land mobile use several months earlier. No American TV station ever broadcast over channel 1. Previously…

Previously…

While television was new to Robinson in 1949, the technology wasn’t new. In fact, the concept dates back to the 19th century.

Both Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison speculated about telephone-like devices that could transmit images as well as sounds, but it was German researcher Paul Nipkow who came up with the “electric telescope,” an early form of mechanical television in 1884. It consisted of a system of spinning discs that sent images through wires.

In the early 1900s, scientists developed ways to replace Nipkow’s discs with cathode ray tubes. Scottish engineer John Logie Baird gave the world’s first demonstration of true television in 1927. Meanwhile, American inventor Philo Farnsworth came up with the idea of using a vacuum tube to dissect images into lines that would be transmitted to receivers that would convert them back into images.

The British Broadcasting Company begun the world’s first regular TV broadcasts in 1936. Three years later, the National Broadcasting Company, a division of RCA better known as NBC, launched with live coverage of the World’s Fair in New York City.

The FCC authorized commercial broadcasting in the U.S. July 1, 1941. The first commercial — a 10-second spot hawking watches — made NBC $7. All television production halted during World War II and NBC switched to broadcasting on a limited basis.

After the war, TV manufacturing and broadcasts resumed, bolstered by improvements in communications improvements by the militiary.

Stay tuned

About six weeks prior to running Rooney’s ad, the Daily News published a front page story about a local bar getting a television.

“A television tower nas been installed at Nick and Joe’s Tavern on the north side of the square here. The tower is one hundred and four feet high with a 12 foot antenna on top of the tower,” the story said.

“Part of the St. Louis Bomber-Washington basketball game from St. Louis was obtained last night despite bad television weather.” The Washington Capitols won 74-65.

“The television receiver at Nick and Joe’s Tavern is one of our installations,” Rooney wrote, urging local residents to drop in and see it. “They have had some very good receptions of both pictures and sound.

“Television is broadcast generally from 6 to 10 p.m. every day,” Rooney continued. “The nation’s favorite sport, baseball, will be going again soon. Imagine the thrill of seeing these games! You can at Nick and Joe’s. And if you hurry, we can have your set installed in your home in time for the opening games April 16th.”

This was standard practice. Retailers knew placing a set in a bar or restaurant where customers could see their favorite teams — perhaps for the fist time — would entice them to want their own home receivers, regardless of the price.

And that price could be steep. In 1940, a set could cost $200 to $600, depending on its size and features. By 1948, most still ran about $400. Two years later, however, sets were available for $100 to $200.

Rooney had high hopes for television, but was quick to point out it still had limitations.

“We have tried not to over sell on the results which you may expect in television reception in Robinson because it is still in it’s infancy,” he explained.

“But we do honestly feel that you can expect fair performance now and as the stations come nearer to us that you can expect it to improve constantly. We intend to maintain our diary of performance of our set so that we can advise you from time to time of our results.”

On the air Rooney’s drum-beating for television eventually earned him the nickname “TV Rooney,” accoriding to a 1965 Daily News article. Despite that, he was obviously no couch potato.

Rooney’s drum-beating for television eventually earned him the nickname “TV Rooney,” accoriding to a 1965 Daily News article. Despite that, he was obviously no couch potato.

His business career began in 1915, when the 15-year-old Rooney went to work in a small grocery/tea shop on North Cross operated by his older brother, Andy. He began running the store on his own when Andy joined the Army to fight in World War I.

When returned from the service, Andy was so pleased with his brother’s efforts he left him in charge. Andy then started a store in Lawrenceville, which he also turned over to Rooney. With his retail establishments in good hands, Andy was free to start Golden Rule Insurance.

Rooney got out of the grocery business and opened his “electric store” on South Cross in 1945. A decade later, having relocated to 709-711 E. Main, Rooney sold the shop to Robert Gwin of Charleston and his brother John of Springfield.

In time, the Gwins moved the store back to South Cross before launching a television spinoff — the Robinson TV Cable Company.

The Robinson City Council granted the Gwins an exclusive 10-year contract to build and operate a “television antenna system” March 7, 1962. In return for a $15 installation fee and a $5.95 monthly subscription, Robinson residents could link to an antenna being constructed by the company. It would offer at least three network affiliates and FM radio broadcasts. General Telephone would lay and maintain lines to houses.

At one point, the company carried about a dozen channels and even tried its hand at creating its own material. For a while, the Gwins broadcast live footage of a wheel that showed information such as the time and temperature on channel 12. On Dec. 27, 1966, they launched a 15-minute evening newscast. Manager Jack Weber would read news, sports and weather, with much of the information coming from the Daily News. That same day, L.S. Heath and Sons Inc. announced the first line at its new plant on the west side of town was in full operation turning out 5-cent Heath bars.

Fires forced the company to relocate three times. From a former grocery in the building that once housed the Daily News, it moved temporarily to the building across the street from the Schmidt Clinic, now the Crawford County Historical Museum. Then, it was back to the Otey Building, one of the sections that have since been demolished.

The Gwins sold the local cable company to Cox Communications in 1969. John Gwinn took a job with the corporation in Atlanta, where he became friends with future media mogul Ted Turner.

The local service was redubbed Cox Cable Robinson. A pair of Chicagoans bought it in 1985 or ‘86 and later sold it to Triax Cablevision, which sold it to Mediacom in 1999.

Meanwhile, Rooney’s former business continued to operate for several years under different owners as Robinson Appliance Mart.

Epilogue

As for Rooney, his retirement was short-lived. He opened a loan business at the Big Four. Meanwhile, he served as president of the Robinson Chamber of Commerce and was a member of the Elks, Moose, Rotary and Knights of Columbus. He was a recipient of the chamber’s Distinguished Citizen Award.

Rooney retired a second time in 1965, but soon was appointed by Gov. Otto Kerner to the Wabash Valley Interstate Commission, a group formed to promote and coordinate conservation and development of area natural resources.

Coincidentally, Terre Haute’s second station, WTWO-TV, went on the air the same day.

Rooney died Oct. 11, 1979, more than three decades after placing his ad in the newspaper. Almost 45 later, the medium he worked so hard to promote continues to evolve and thrive.