I’m excited to shine a light not only on a new book of poetry but also on a new small press: Winter Editions began publishing titles in May of this year varying from titles that are five decades old but out of print to debut collections of poetry. While “big 5” publishers get books in the hands of people across the planet in meaningful ways, the tireless yet rewarding work of small press publishing allows for voices and aesthetics we might not otherwise encounter. The ethos of Winter Editions is that it “supports writing which pursues an ‘other’ way—opposing generic constructs and codified forms, or offering unfamiliar, outsider, or marginalized perspectives…Dreaming of social and aesthetic engagement beyond commodity, hierarchy, and exclusion, WE publishes for readers who desire intimate, unquantified relations.” It doesn’t have social media—it focuses instead on making great books and gets them in bookstores and libraries.

Ahmad Almallah’s second collection, Border Wisdom, is among them. We’re at a stunning moment in the world—but also the world of literature. The Frankfurt Book Fair cancelled an award ceremony for Adania Shibli; the 92NY disinvited Viet Thanh Nguyen for his signing an open letter calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, among other things. It’s urgent we heed voices of the historically and systematically unheard—especially Palestinian authors like Almallah (who has lived in the United States for some years). Border Wisdom thoughtfully incorporates of Arabic, English, prose-poems, a variation of fonts to illustrate a multivocal or at least multitonal text. The latter varies from somber to jokey or satirical. One of the most moving portions of the collection is a series of poems that acts as a loving paean to his mother—“You clung to my hand like I was / that small body you made / and named.” This terrible loss (which he calls again and again a “disappearance”) and its previous looming inevitability are made even more fraught for Almallah due to his distance—and where his mother lived. Palestine was and is a place often defined by danger and violence. While living in Lebanon, Almallah resorts to witnessing this on the news:

Sometime in May, another war in Gaza is on its way—

in the room we save for the living, I watched the buildings

leveled to the ground dust and some more dust

rising in a cloud

Addressing his mother in the intimate “you,” he goes on:

I was in Beirut calculating my next move: should

I go back and wait for your eventual

disappearance…I thought you’ll wait for me, for us,

time and again— I was wrong.

Ultimately, she died in the hospital where Almallah was born. At one point, Almallah ironically writes, “that’s how Palestinians lose their battles. Their suffering is so detailed and absurd that when they try to tell it to the world, they step into a critical defeat: the overdramatic!” To read an excerpt of the collection, you can access Jerome Rothenberg’s selection of poems from Border Wisdom in Jacket2. Divya Victor says of Border Wisdom, “Ahmad Almallah observes the dust that rises when war and grief collide in the rubble of brief existences made briefer by geopolitical devastations. These poems honor the daily trembling and unexpected questions that accompany the losses of one’s spaces of origin—one’s mother, one’s land, one’s language.”

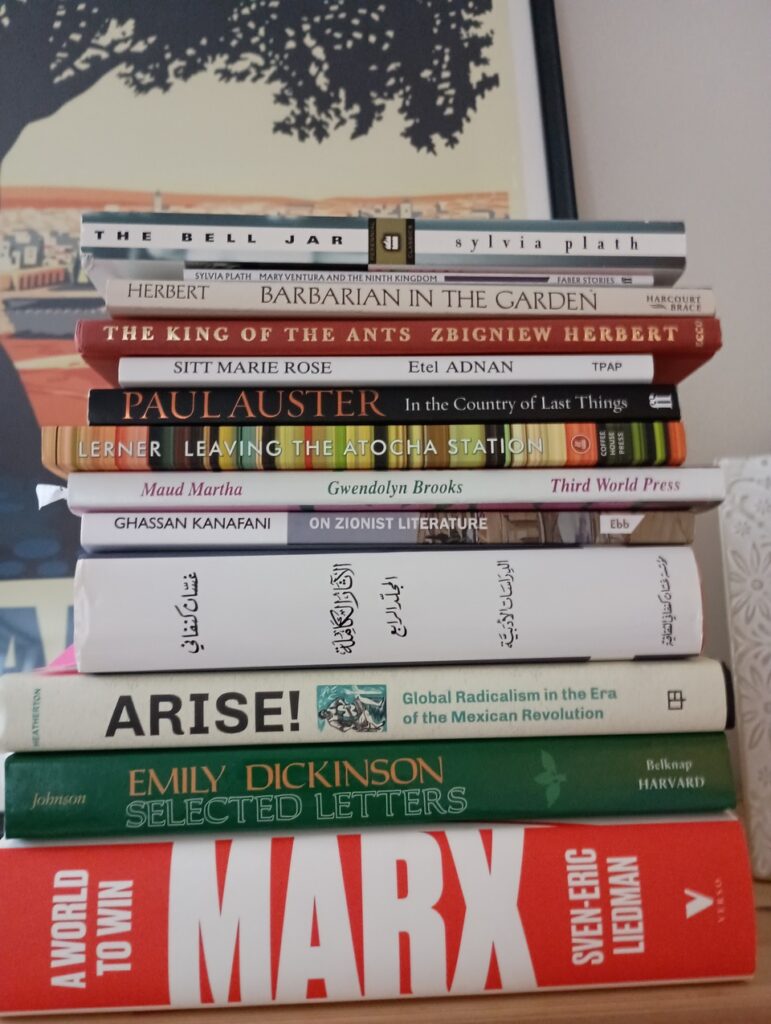

Regarding his to-read pile, Almallah tells us, “Before putting Border Wisdom together, I hit a dead end trying to write a novel. My way out now is to read much prose by some of my favorite poets. I also left room for other interesting and urgent prose out there…here I especially point out the new translation of one Palestine’s literary and political icons, Ghassan Kanafani (might his voice and vision bring some attention to Palestinians and their struggle for dignity and life since their land was promised to the Zionist Federation by the British colonizers in 1918).”

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Whenever a canonical/famous text comes up in a guest’s pile, I like to dig for random factoids about it. Early titles for Plath’s sole but remarkable novel were The Girl in the Mirror and Diary of a Suicide. Apparently, she hewed so closely to the reality of the students that populated The Bell Jar that people were able to identify themselves, each other—to such a degree it created scandals and busted up marriages. The Bell Jar came out just weeks prior to Plath’s death, obviously coloring how people read it. It sold wildly well, going into a third printing in just a month. It remained on the bestseller list for almost half a year. I’m sure Harper & Row had to sit and think about the fact it was promised to them but they rejected it, saying, it was “disappointing, juvenile and overwrought.” Some of the poems that Plath wrote in the posthumously published Ariel were scratched out on the clean sides of Bell Jar draft pages.

Sylvia Plath, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom

This is a story Plath wrote when she was only twenty, recently published for the first time. It follows the titular Mary as she rides on a train, initially caught up in the opulence—only to realize there’s something dark about the train’s final destination. Heather Clark at Harvard Review writes of the piece, “[Plath’s] structure was Dantean—she had been reading Dante in November 1952—yet the story’s real subjects are depression, suicide, and rebirth. Plath had been writing short stories since she was a child, but ‘Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom’ marked the first time she had faced, albeit obliquely, what she called her mental ‘difficulties’ in fiction. The story shows Plath already grafting an allegorical trajectory onto her psychological struggles—mining them, even in the depth of her depression, for creative potential.”

Zbigniew Herbert, Barbarian in the Garden (tr. Michael March & Jaroslaw Anders)

In 1983, Bogdana Carpenter wrote of Polish writer Herbert’s use of the image of “the barbarian” in his work. Carpenter explains, “The barbarian is a savage, the inhabitant of a country at the periphery of the civilized world…[T]he concept of the barbarian suggests a straightforward system of values based on a cultural hierarchy and implying inferiority on the one hand (the barbarian) and superiority on the other (civilization, the garden). However, a deeper reading of Herbert’s work undermines this simplistic conclusion, revealing the ambiguity in his use of the term and the complexity of his attitude toward the West. This represents one of the most original and striking features of his writing. It challenges many of the commonly held attitudes about civilization—about what it is and what it is not—as well as the values we associate with it.”

Zbigniew Herbert, The King of the Ants: Mythological Essays (tr. John Carpenter & Bogdana Carpenter)

Herbert was lauded for his work throughout his life, and was one of the most well-known post-WWII Polish writers who opposed communism. His work has been translated into dozens of languages and, when he died, Richard Eder in the New York Times says Herbert was “perhaps an artery or two away from a Nobel.” And here we have a scholar of his work (as quoted above) also acting as his translator! Eder’s review of the collection states, “‘King of the Ants’ is 11 prose variations on Greek myths, most of them speaking out for the underdogs. There is a nice sketch of Atlas forced to do the drudge work of holding up the heavens. As the gods—read the privileged—would say, ‘Someone must do it.’ It is minor Herbert, on the whole, though the poet’s wit and moral bite are evident.”

Etel Adnan, Sitt Marie Rose (tr. Georgina Kleege)

The beloved writer and visual artist’s novel fictionalizes the death of Marie Rose Boulos, a Syrian immigrant in Lebanon—Adnan’s home country—who coordinated welfare services for Palestinians and also acts as instructor for deaf-mute children during the Lebanese Civil War. The Christian militia executed Boulos. Sitt Marie Rose attends to this death from the perspectives of seven different people, allowing Adnan to comment on misogyny and Lebanese xenophobia. As a side note, reading about Adnan, I saw she was a member of an art movement I was otherwise ignorant of called the Hurufiyya movement. This was a 20th century Muslim art movement grounded in traditional Islamic calligraphy in conjunction with modern art.

Paul Auster, In the Country of Last Things

Auster is known for many things, including his work for PEN American Center. In 2012, Auster’s work was to be published in Turkey. He vowed in a Turkish newspaper never to go to the country “because of imprisoned journalists and writers…How many are jailed now? Over 100?” Wildly, the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan responded to this statement with, “If you don’t come, so what? Will Turkey lose prestige?” Auster published a response, which reads, in part: “All countries are flawed and beset by myriad problems, Mr. Prime Minister, including my United States, including your Turkey, and it is my firm conviction that in order to improve conditions in our countries, in every country, the freedom to speak and publish without censorship or the threat of imprisonment is a sacred right for all men and women.” If you haven’t read In the Country of Last Things, you can find an excerpt of it here.

Ben Lerner, Leaving the Atocha Station

James Wood in his review of Lerner’s debut novel in the New Yorker writes, “Adam Gordon, the narrator of Ben Lerner’s subtle, sinuous, and very funny first novel, ‘Leaving the Atocha Station’ (Coffee House; $15), is a descendant of those frustrated Russian antiheroes. He is a young American poet who, in 2004, is spending a fellowship year in Madrid; his project is “a long, research-driven poem” exploring the legacy of the Spanish Civil War. If that “research” sounds like the boxed-up confection that people present in order to get fellowships abroad, that’s because it is: Adam knows little about the Civil War and not much about Spanish poetry. In Madrid, like one of Herzen’s young men in a dressing gown, he spends his time reading Tolstoy, Ashbery, and Cervantes, going to parties, downing tranquillizers, smoking spliffs, trying and largely failing to love and be loved by two Spanish women, Teresa and Isabel, and dodging the head of the foundation that has funded his sojourn.”

Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha

I realize it’s hard for me to make a compelling argument that Brooks is one of the most overlooked geniuses of American literature—she was the first Black American to win the Pulitzer Prize. But I didn’t learn about her work until I was almost 30. Her writing is out of print save for a recently published selected works (assembled by Elizabeth Alexander, Brooks’ contemporary champion). Alexander says of Brooks’ poetry, “Her formal range is most impressive, as she experiments with sonnets, ballads, spirituals, blues, full and off-rhymes. She is nothing short of a technical virtuoso.” Maud Martha, however, is Brooks’ sole novel—but it continues to trace the predominant concerns Brooks returned to with acuity throughout her oeuvre along with its undeniably brilliant language. Asali Solomon says of the novel on NPR, “[Maud Martha is] the story of a girl who becomes a woman in 1940s black Chicago, told with minimal drama and maximal beauty. The plot here resembles your life or mine: good days and bad, no headlines. But Maud Martha‘s riotous parade of human feeling will make you wonder what Brooks could have done with your life story.” To give an example, Maud sees her husband openly flirting and dancing with someone. She thinks of attacking this woman, but then decides, “if the root was sour what business did she have up there hacking at a leaf?”

Ghassan Kanafani, The Complete Works of Ghassan Kanafani (volume 4)

Kanafani was a Palestinian author and activist who helped lead the Popular Front for Liberation of Palestine. He was assassinated in Beirut at the age of 36 in 1972 by Israel’s intelligence agency Mossad. This volume contains Kanafani’s critical work, including “On Zionist Literature,” which is now also available in English translation by Mahmoud Najib. The publisher of Najib’s translation states of the work, “Translated into English for the first time after its publication in 1967, Ghassan Kanafani’s On Zionist Literature makes an incisive analysis of the body of literary fiction written in support of the Zionist colonization of Palestine. Interweaving his literary criticism of works by George Eliot, Arthur Koestler, and many others with a historical materialist narrative, Kanafani identifies the political intent and ideology of Zionist literature, demonstrating how the myths used to justify the Zionist-imperialist domination of Palestine first emerged and were repeatedly propagated in popular literary works in order to generate support for Zionism and shape the Western public’s understanding of it.” Considering the active silencing of Palestinian voices and pervasive ignorance surrounding the context of what is happening in Palestine today, this seems like required reading.

Christina Heatherton, Arise!: Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution

In an essay, Heatherton that writes that her book “was born of family lore. Many of my Okinawan relatives, including one great-uncle, came to the United States via Revolutionary Mexico. Morisei Yamashiro became a farmworker and labor organizer in the fields of Southern California’s Imperial Valley. There, Okinawan, Japanese, Chinese, Black, Filipino, South Asian, Indigenous, poor white, and Mexican workers labored together… This story was provocative for several reasons. I knew of the world of the Revolutionary Atlantic and the radical currents which produced what Julius C. Scott calls the “common wind” of abolition. I first wondered if there might be a story to tell about the Revolutionary Pacific and the influence of the Mexican Revolution upon it. The story further challenged my understanding of Asian American radical history. Instead of resistance to nativism and exclusionary laws, I wondered how to make sense of a possible solidarity between Okinawans and Japanese migrants with Indigenous peasants during the Mexican Revolution and its influence upon radicalism in the United States.”

Sven-Eric Liedman, A World to Win: The Life and Thought of Karl Marx

In its review of this doorstop of a book Kirkus writes, “‘It is the Marx of the nineteenth century, not the twentieth, who can attract the people of the twenty-first,’ [Liedman] writes, meaning that despite the deformities introduced to Marxist doctrine by way of the practical—and totalitarian—politics of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao, there are still good bones in the house that Marx built. Liedman examines the man and his ideas alike, sometimes finding unpleasant moments in both… Some readers may wish that Marx had gone with his earlier desire to become a poet instead of a philosopher of such matters, but this book makes clear that Marx’s ideas, going on two centuries old, still have meaning in the present. Outstanding. Not the book for a budding Marxist to start with, but certainly one to turn to for reference and deeper insight.”