“…In the search for a harmonious attitude towards life, it must never be forgotten that we ourselves are both actors and spectators in the drama of existence.” – Niels Bohr, physicist

–

During World War Two, the US government formed the Manhattan Project, recruiting scientists and engineers from across the country to live and work at a secret research centre in Los Alamos, New Mexico. From this base in the desert, and under the leadership of Robert Oppenheimer, they developed the world’s first atomic bombs.

On 21 May 1946, the physicist Louis Slotin was in his final weeks of working for the Project. He was an expert in bomb assembly and had played a central role, hand-building the “Trinity” device for the first test in July 1945, just a month before the Fat Man and Little Boy atomic bombs were dropped on Japan. But, like Oppenheimer, in the months that followed, he came to object to the continuation of the nuclear weapons programme and had decided to go back to civilian life.

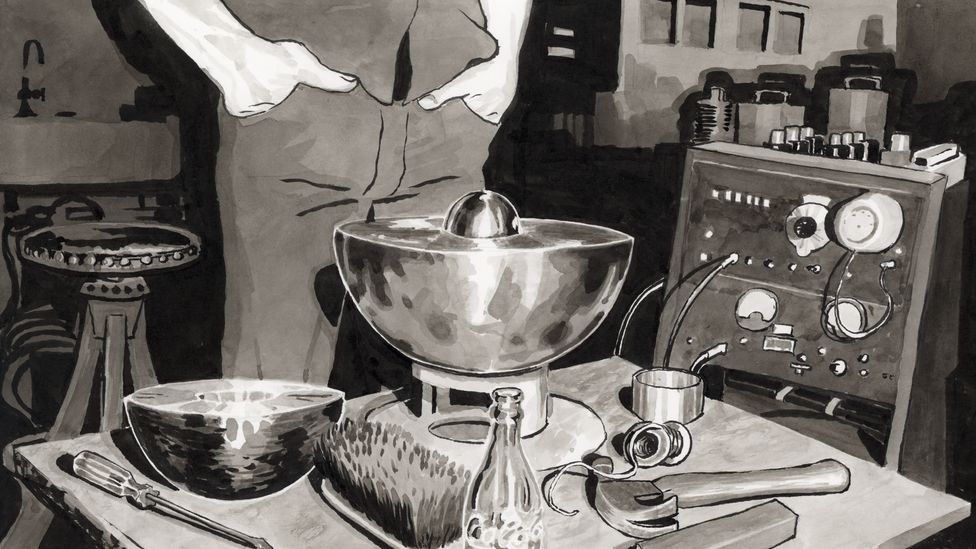

Slotin was giving a tour to Alvin Graves, the scientist who was due to replace him. A little before 15:00, in the middle of one of the laboratory buildings, Graves spotted something he recognised: the “critical assembly”, which was Slotin’s specialism. Like an experimental nuclear bomb, it was used to safely test the reactivity of a plutonium core.

The “critical assembly” was comprised of a plutonium core and two hemispherical neutron “reflectors” made of beryllium.

Graves commented that he had never seen the assembly demonstrated. Slotin offered to run through it for him.

Alvin Graves (left) and Louis Slotin (right).

From the other side of the room, Raemer Schreiber, Slotin’s colleague, agreed. However, he encouraged him to proceed slowly and with caution:

Slotin’s colleague, Raemer Schreiber, who had helped assemble the Fat Man bomb, dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945.

Schrieber would later say this comment was not entirely serious since “we all had confidence in Slotin’s ability”.

The idea was to bring the core to a stable rate of reactivity and hold it there, rather like starting a car’s engine and allowing it to tick over.

Using as screwdriver for support, Slotin lowered the upper hemisphere over the core, reflecting neutrons back into it, gradually increasing the rate of reactivity inside.

There are conflicting reports about what went wrong. An onlooker said Slotin’s approach on this occasion was “improvised”. Others said what he did was perfectly normal. In Schreiber’s official report, he said Slotin acted “too rapidly and without adequate consideration”, but that the others in the room “by their silence, agreed to the procedure”.

The screwdriver slipped and the upper reflector enclosed the core.

“I turned because of some noise or sudden movement,” wrote Schreiber. “I saw a blue flash… and felt a heat wave simultaneously.” It seems the screwdriver had slipped and the plutonium had gone “prompt critical” as the reflector dropped down over it. It happened, as Schreiber wrote, in “a few tenths of a second.” Slotin flipped the upper reflector to the floor, but his reaction was already too late. In the moments after the accident, the room was silent.

Then Slotin said quietly:

Slotin knew the implications of what had happened.

The aftermath was remembered chaotically. The scientists gathered in the corridor outside. Slotin sketched a diagram of where they had each been standing at the moment of the accident. Schreiber, who’d been furthest away, went back in and tried to get radiation readings. While he was there, he also collected his jacket. One internal report on the accident says humans are in “no condition for rational behaviour” after radiation exposure. It also says they may experience “vertigo”. It doesn’t say whether this is a direct effect of high-energy particles or some response of the body to the imminence of death.

Slotin died nine days later from organ failure. “A pure and simple case of death from radiation,” as a colleague would later describe it.

Slotin’s left hand three days (left) and nine days (right) after the accident – drawn from archival photographs.

Had Slotin simply grown careless, as official histories suggest? Or was the accident caused by something harder to detect?

During the 1940s, in parallel with the atomic bomb’s development, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr was working on the new science of quantum mechanics, a discipline with some profound implications for the idea of scientific objectivity. Unlike events described by classical physics, Bohr said, quantum activity could only be measured through physical interaction with the particles concerned; interaction that inevitably changed both the particles and the equipment used to measure them.

Physicist Niels Bohr.

Objectivity was not a question of passive observation but of “permanent marks – such as the spot on a photographic plate, caused by the impact of an electron – left on the bodies which define the experimental conditions”. In an important sense, quantum phenomena were inseparable from the equipment employed in their measurement and, by extension, from the people that used the equipment.

Through his choices, Slotin turned his own body into a part of the experimental apparatus.

When Bohr spoke of “bodies” defining experimental conditions, he was probably thinking of apparatus rather than of human bodies. But by manually handling the critical assembly that day, Slotin turned his own body into a part of the apparatus, into both a biological register of quantum effects and into one of the materials that was causing those same effects. A 2018 reconstruction of the accident suggested the plutonium core would not have gone critical had it not been for his hand on the beryllium hemisphere acting as an additional neutron reflector.

Slotin in the moments before the accident.

Tragically, Slotin’s death was not unprecedented: he had watched a colleague die after a very similar accident the year before, involving the same plutonium core.

Slotin’s colleague, Harry Daghlian, who died handling the same plutonium core a year earlier, in 1945; drawn from film stills shot the same year.

In fact his boss, Enrico Fermi, had explicitly warned Slotin only a few months earlier about his approach to critical assemblies. “You’ll be dead within the year, if you keep doing that,” he had said.

But it seems Fermi’s was a lone voice in an institution that tended to downplay the dangers of its work. Lieutenant Edward Wilder who served on the Los Alamos High Explosives and Assembly Team during WW2, later recalled fires, electrocutions and explosions at the lab. He once saw a man swallow a fragment of high explosive that accidentally flew into his mouth. “In these times,” as he put it, “there was no safety organisation.”

Edward Wilder rides the “Fat Man” bomb in 1946, before it was dropped on Nagasaki. Drawn from an original photograph provided by Wilder’s son Marshall.

At Los Alamos, two simultaneous realities were at play. In the first, the gravity of the work was overwhelming. As the physicist Phillip Morrison put it in 1986: “There was no doubt in our minds that the German government… was in possession of the means of the most powerful weapon that the world had ever seen… the reaction was great anxiety and fear.” In the other reality, the use of human bodies in defining experimental conditions was common practice and the work’s implications were disguised by what physicist and feminist theorist Karen Barad calls a culture of “play” and “anti-realism”.

Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Manhattan Project.

A blinkered pursuit of the “sweet” can still be seen in science and technology today, such as in the burgeoning field of artificial intelligence. Even projects that appear benign may have calamitous potential. In 2022, researchers at a drug development company decided to test if its software could also create biochemical weapons. Within six hours, the AI had identified more than 40,000 compounds “predicted to be more toxic… than publicly known chemical warfare agents”.

“The thought had never previously struck us,” wrote the authors. “We were naive in thinking about the potential misuse of our trade… A non-human autonomous creator of a deadly chemical weapon is entirely feasible.”

Niels Bohr once defined an “experiment” as “a situation where we can tell others what we have done and what we have learned”. From this perspective, Slotin’s accident was a missed opportunity; a minor entry in a long history of technological wake-up calls that have been poorly recorded and at best partially examined. Thousands attended his funeral. His hometown named a park after him. But there was little public discourse around what his death might mean. According to one researcher the US government “established a pattern of secrecy”, in response to Slotin’s death “that still persists”.

Relatively unscathed by the accident, Schreiber went on to help re-design the way procedures like the one that killed Slotin were conducted, with a greater emphasis on safety.

Standing at Slotin’s shoulder, Graves received a high dosage of radiation and became critically ill. The official reports seem to downplay the effects – the permanent impairment of vision in his left eye, or the many months it took for his sperm count to recover. One report stated: “The patient felt well 38 months after exposure. He was working extremely hard in a position of great responsibility…”

The regrowth of Alvin Graves’ hair, drawn from anonymised archival photographs taken one, two and four months after the accident.

Floy Agnes Lee, the haematologist treating Graves after the accident described in a 2017 interview how severe his condition was. “His white blood cells were so low that they didn’t understand why he was still living,” she said. “I don’t remember how long it took before his hair started growing back again.”

Graves went on to become the chief scientific officer at Los Alamos. During the Cold War, he oversaw many of the most destructive weapons tests in history, vaporising whole Pacific islands, irradiating swathes of ocean ecology, and leaving a terrible nuclear legacy for the people who live there. Raised rates of cancer and still birth were reported, not to mention the damage caused by the evacuation of homelands.

The inhabitants of Bikini Atoll, evacuated in 1946 to make way for nuclear weapons tests.

In a testimony to the International Court of Justice in 1995, the advocate, Lijon Eknilang, from the Marshallese island of Rongelap, described the impact of the tests on successive generations of her community:

Marshallese activist Lijon Eknilang speaking to the International Court of Justice in 1995.

“The fall-out was in the air we breathed, in the fresh water we drank, and in the food we ate… Some of our food crops, such as arrowroot, completely disappeared. Makmok, or tapioca plants, stopped bearing fruit. What we did eat gave us blisters on our lips and in our mouths and we suffered terrible stomach problems and nausea… we later experienced other, even more serious problems… Our illnesses got worse, and many of us died. We had to believe that our island was radioactive, and we evacuated ourselves from Rongelap in 1985. The Rongelapese have been living in exile ever since.”

Coral atolls, such as those in the Marshall Islands, take up to 10,000 years to form. US nuclear tests destroyed whole islands, leaving craters visible in satellite images.

The former US Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, later suggested that Graves’ experience of the accident in 1946 protected him from criticism: “No one had the temerity to challenge [his] reckless safety policies’ because he had the measure of radiation ‘from personal experience’.”

Alvin Graves speaking in 1965.

The lump of plutonium that killed Slotin was later nicknamed the “demon core”. In March 1965, four months before his own death, Graves gave a speech in which he used a different, if equally colourful, metaphor, naturalising the existence of nuclear weapons by comparing them to “man-eating sharks”.

“All the instincts of a shark must tell him that that helpless succulent morsel in the water with him is just what he wants and should have,” he said. “The question of immorality does not arise. It seems to me the question of morality enters the picture the moment that man enters the picture and not before. Hence, I can think of atomic bombs being used for immoral purposes but not being of themselves immoral.”

He explained that stockpiles of atomic weapons made nuclear war “unthinkable”, buying time for negotiation between enemies. “New advances in the tools of war,” he added, “have almost always brought about new advances in the tools of peace.”

As for Slotin’s death, Graves left no comment behind. He was, an official memo records, “reluctant to discuss it”.

Louis Slotin died 30 May 1946

*All illustrations and text are by Ben Platts-Mills, a writer and artist whose work investigates power, reasoning and vulnerability, and the ways science is represented in popular culture. His memoir, Tell Me The Planets, was published in 2018. On Instagram he is @benplattsmills.

Commissioned and edited by Richard Fisher.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.