As the middle grade graphic novel category has grown in recent years, the number of graphic adaptations of middle grade books has exploded. That makes sense: graphic adaptations bring new readers to older stories and expand the audience for newer ones. In the early days of the medium, they also helped graphic novels gain acceptance in the eyes of educators, parents, and librarians.

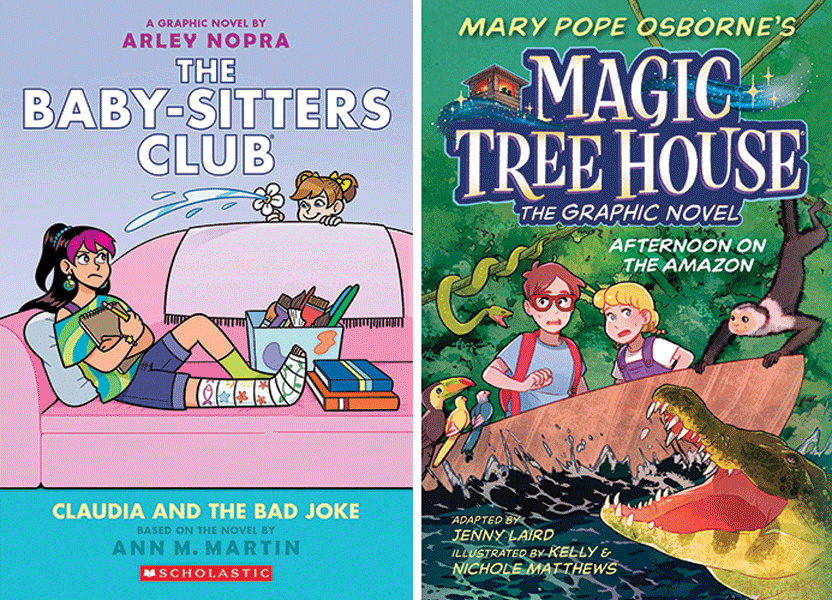

When David Saylor launched Scholastic’s graphic novel imprint Graphix in 2005, middle grade graphic novels were still a small category, and one that often got the side-eye from gatekeepers. “There were a lot of parents and teachers that were saying graphic novels are not books,” he says. “They were anxious about comics. They thought they were problematic in some way.” So he turned to the books that parents and teachers themselves grew up with, creating graphic novels based on Ann M. Martin’s Baby-Sitters Club chapter books.

It worked. The first Baby-Sitters Club graphic novel was published in 2006; now there are 15 volumes of that title and six more in the Baby-Sitters Little Sister spinoff series, and all are consistently bestsellers.

Less than 20 years later, the script has flipped, and publishers are using graphic adaptations to attract the burgeoning middle grade graphic novel audience to their books. “We all know the graphic novel market is the biggest growth market out there right now, so it’s partly meeting kids where they are, giving them what they want to read,” says Shana Corey, editorial director of Random House Graphic and the editor of Chris Grabenstein’s Escape from Mr. Lemoncello’s Library: The Graphic Novel.

Martin herself sees new readers coming to the Baby-Sitters Club books, which launched in prose form in 1986, from the graphic adaptations. “I think it’s probably kids who are looking for something to read and were drawn to graphic novels and found them that way,” she says, “but I also hear on Facebook from adult fans who read the books years ago that they are introducing their kids to the series, sometimes through the original editions but often through the graphic novels.”

Graphic adaptations expand the audience in other ways. Corey, who grew up reading Mary Pope Osborne’s Magic Tree House books, thinks the cool factor makes the graphic novels a little easier for older kids to read.

Kara Sargent, director of branded publishing at Aladdin and editor of the graphic adaptation of Shannon Messenger’s Keeper of the Lost Cities, thinks that size matters as well. “Shannon’s novels are very chunky,” she says. “They’re big, thick, long novels, and not every reader is drawn to a book like that. A graphic novel is a new way of telling the story, and hopefully it will bring some new fans to the series.” The graphic adaptation also divides the first volume of the novel into two parts, which readers may find more manageable.

Series keep kids coming back

It’s no coincidence that so many middle grade adaptations are of series—often older ones. “When kids find something they love, they want to keep reading,” Corey says.

“It’s like candy—you just want the next one,” Saylor agrees. “Even though kids read graphic novels over and over and over again, they do read them quickly,” he says, “so series publishing only makes sense.”

For publishers, graphic adaptations attract new readers to older series. Susan Kochan, associate editorial director at Putnam, sees the graphic adaptation of Paula Danziger’s Amber Brown Is Not a Crayon as a way to bring the character, who first appeared in 1993, to a new cohort of readers in both formats. “Hopefully we’ll get great review coverage, and then people will go back to the original as well,” she notes.

Saylor says sales of the Baby-Sitters Club books went up when the graphic novels gained popularity. “It spurred sales of the prose books, because fans don’t necessarily stick to one format,” he says. “If you like something, you’ll read the graphic novel, you’ll read the prose book, you’ll see the movie or watch it on Netflix. There are all these different ways to enjoy it.”

Graphic adaptations also give readers a way to approach longer series, such as Sweet Valley Twins, which is part of a franchise with more than 200 prose books. “The graphic novels are a good entry point,” says Whitney Leopard, executive editor at Random House Graphic, who edits the Sweet Valley Twins graphic novels. “The kids can start reading the graphic novels, and they can jump into more adventures if they have that available to them in a different format.”

As the category matures, older graphic novels can even get a boost from new prose books. In 2012, Random House published a graphic adaptation of Jeanne DuPrau’s The City of Ember, which was a bestseller back in 2003. When DuPrau’s new prose book, Project F, was published last October, Random House released new editions of both versions of the older title as well. “That graphic novel has sold for years,” says senior v-p and publisher Michelle Nagler, “but we saw everything rise: Project F, the City of Ember paperback, and the City of Ember graphic novel all sold better this fall.”

While graphic novels of all types are enormously popular right now, the value of a known quantity can’t be discounted. “We get placement in the bookstores right away for something like Sweet Valley Twins, because the booksellers know it,” Nagler says. On the other hand, she adds, “the nostalgia gets you in the door, but it’s not going to keep the kids there. The fact that Sweet Valley has continued to stay, and each book is hitting the bestseller list, and that our sales have grown—that’s not about brand recognition at all. That’s about Francine Pascal’s timeless stories and the adaptations that make it current.”

Updates and tweaks

One benefit of adaptations is that they allow editors to update the books, taking out the corded phones, modernizing hairstyles, and generally bringing things up to date. That includes making the cast more diverse.

“Francine Pascal said, ‘I want this to reflect a modern-day classroom. I want kids to be able to see themselves,’ ” Leopard says. “It was great to have that conversation with her, where diversity was such a focus.”

Artist Anu Chouhan drew Snow White as East Asian and the prince as South Asian in her adaptation of Sarah Mlynowski’s Whatever After: Fairest of Them All for Graphix, reflecting a historical reality that doesn’t always show up in contemporary works. “That’s what people look like in the real world,” she says, “and even in the medieval era, there were people of color in major cities.”

Escape from Mr. Lemoncello’s Library already had a diverse cast, Corey says, but the adaptation offered another opportunity. Grabenstein includes references to other books and authors in his stories, and with the adaptation, Corey adds, “we were able to bring in more recent and more diverse books. That was really important to him.”

Keeping the heart of the story

The adaptation process varies from publisher to publisher; sometimes a new writer adapts the script, sometimes the artist does all the work, and the original author is usually involved as well. Editors and adapters have to balance the old and the new, keeping the essence of the book while translating it to a new medium. “It’s a bit of an editing process,” Saylor says, “in terms of what are the important notes that you want to hit and what things do you need to have in the book and what things can you leave out.”

It wasn’t difficult for Grabenstein, who wrote the script for the adaptation of Escape from Mr. Lemoncello’s Library. “He said he knew how to tighten it and where: things that have never been mentioned in fan letters were the things that he deleted as he was writing the script,” Corey recalls. “He was like, ‘No one has ever said that was their favorite scene. Out it goes!’ ”

On the other hand, Osborne was initially reluctant to allow the Magic Tree House books to be adapted, Nagler says. “It wasn’t a slam dunk, because Mary is really thoughtful about the Magic Tree House world. When she decided she wanted to do it, she jumped in with two feet.”

One thing that helped: adapters Kelly and Nichole Matthews were fans of the books when they were kids, and the enthusiasm they brought to the project helped bring it to life.

Because many of the series currently being adapted are older, the editors and adapters are often longtime fans. Leopard read the Sweet Valley books when she was growing up, and the Baby-Sitters Club books were favorites of Raina Telgemeier’s, a fact she happened to mention in a casual conversation with Saylor and editor Janna Morishima 20 years ago.

“We had already been thinking we were going to adapt them,” Saylor says. “It was just a matter of finding the right artist. As soon as we heard that Raina had grown up with them and loved them, we were like, ‘You’re the right person to adapt this!’ ”

Other adapters simply resonate with the original, as Victoria Ying did with Paula Danzinger’s Amber Brown books. “Paula had an amazing throughline right to kids’ emotions—the happy things as well as the sad and hard things,” Kochan says. “And we were lucky enough to find Victoria, who had that same through line to her inner child.”

For Chouhan, who has adapted not only Whatever After but also Roshani Chokshi’s Aru Shah and the End of Time, the key is to keep it loose and let the reader use their imagination, just as they would if they were reading prose. “You can’t overthink it,” she says, “because it’s going to come across as very stiff. I’m not extremely detailed with my art in my graphic novels, so there’s still that kind of wiggle room where a kid reading this might be able to imagine what happened between panel one and panel two.”

In the end, Saylor says, “with the right people and the right minds behind it, you can adapt pretty much anything.”

Brigid Alverson is a journalist who writes about comics and graphic novels.

Read more from our comics feature:

Should Comics Keep It Direct?

Direct market distribution has, for decades, been a keystone of comics culture, but its future is up for debate.

From Middle Grade Novel to Graphic Novel

There’s more to adapting a chapter book into a graphic novel than just drawing pictures to go with the words. Adapters often bring a whole new level of nonverbal communication to the page.

A version of this article appeared in the 03/11/2024 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: Middle Grade Goes Graphic