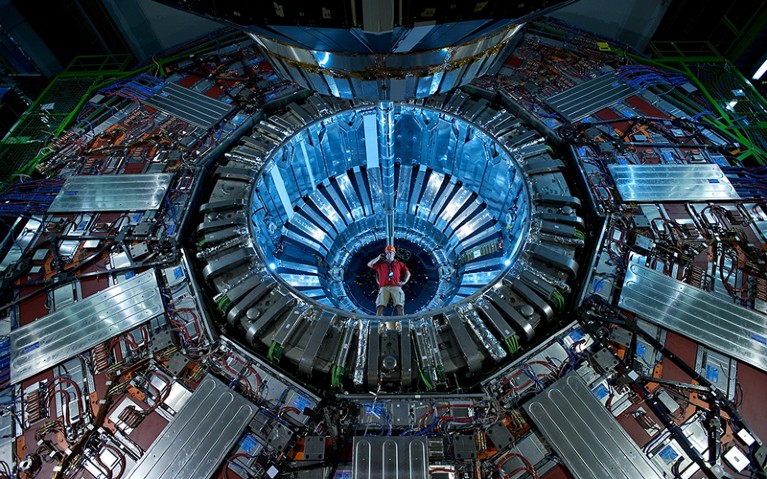

The CMS detector at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab near Geneva, Switzerland, where researchers found evidence of the Higgs boson.Credit: Fons Rademakers/CERN/SPL

Grace in All Simplicity: Beauty, Truth, and Wonders on the Path to the Higgs Boson and New Laws of Nature Robert N. Cahn & Chris Quigg Pegasus (2023)

In Grace in All Simplicity, particle physicists Robert Cahn and Chris Quigg offer a personal tour of humanity’s quest to understand nature and the laws of physics. It is scientific journey as adventure story, a rollicking folk history with plenty of science — from risky experiments on mountaintops to machines buried in deep caverns, from the predilections of eighteenth-century gentleman scientists to the huge, choreographed collaborations of modern particle physics.

The book is billed as the authors’ recommended route through the field. It is like being shown around their hometown, dodging through buildings and hopping fences rather than following the main road. It might be slower, but it’s more memorable and fun.

Could the Universe be a giant quantum computer?

It is an authentic view and few people are this well qualified to give it. As leaders in their field, Cahn and Quigg have witnessed many of the more recent discoveries they relate. They have met scientific giants such as Paul Dirac, who predicted the existence of antimatter and helped to found quantum mechanics. They describe heroes and colleagues with reminiscences of the type you would hope to hear at a conference bar, which rarely get written down.

Cahn and Quigg describe vividly how early attempts to investigate electricity in the eighteenth century were shocking in many ways. French chemist Charles François Du Fay had himself suspended from silk threads and charged with static electricity; when his assistant approached, Du Fay emitted “sparks of fire”.

In the 1920s, scientists tried to break up the atom. A striking effort was made by German physicists Arno Brasch, Fritz Lange and Kurt Urban — who had “an adventurer’s disregard for personal safety”. The trio hoped to suspend a 1.6-kilometre wire net between two Swiss mountains to harness millions of volts from thunderstorms. Their half-size prototype succeeded in attracting lightning, but their research ended in 1928 when Urban fell almost 50 metres to his death, possibly struck by a bolt.

Particle, wave, both or neither? The experiment that challenges all we know about reality

The authors describe how subatomic particles were investigated in cosmic rays — energetic particles that come to Earth from space — by scientists including Giuseppe Occhialini. This Italian experimenter “not only had a great nose for physics, he also knew how to live”. In the 1940s, Occhialini left an experiment gathering data for a month in an observatory in the Pyrenees while he went mountaineering.

We learn how quantum theory was developed, and how antimatter and fundamental particles, including the Higgs boson that gives fundamental particles their mass, were discovered. Cahn and Quigg capture the audacious abstract thinking of theoretical physicists, such as Murray Gell-Mann, who explained groups and internal structures of particles. These researchers arranged particles in patterns according to their properties and then hypothesized that those patterns arose from invisibly small components — quarks, an idea that seemed “too simple to be true” according to the authors. Even Gell-Mann admitted that it was far-fetched; he considered quarks useful “mathematical fictions”, and said that the concept that they might be real was “for blockheads”. That changed in 1974, with the discovery of a particle that contained the charm quark. At that point, “quarks became real”.

Eyewitness account

Personal recollections add to the stories. Quigg remembers asking Dirac an impertinent question about his prediction of the positron (the electron’s antiparticle) after a seminar; Dirac responded with an “ironic wrinkle of an eyebrow”. During a summer job, Cahn repurposed part of a washing machine for an experiment with future Nobel prizewinner Richard Taylor.

The topics and timeline zigzag around, which can be disorientating, but the science moves firmly forward. Quigg and Cahn throw in dashes of cosmology, dark matter and dark energy, along with smatterings of superconductivity, chemistry, string theory, multiverses — and even cephalopod eyes, invoked to introduce the telescope.

A prototype device used to harness lightning on Mount Generoso, Switzerland, in 1928.Credit: A. & E. Frankl/ullstein bild via Getty

Each insight extends our understanding. Phenomena are discovered, investigated, catalogued, then raise deeper questions, demonstrate deeper connections and show deeper principles. The book is a fantastic encapsulation of the brazen way science advances by repurposing and appropriating ideas, keeping the ones that match experimental data.

The authors do a great job of showing how science works on a human level. Many names might be familiar, but Cahn and Quigg capture the personalities — whether it’s Ernest Rutherford, on hearing he has won a fellowship at the University of Cambridge, UK, declaring that he will never again dig up another potato in his New Zealand family garden, or Enrico Fermi fervently sketching out his ideas about radioactivity after a full day’s skiing. Lesser-known scientists are featured, and even animals — such as the ferret Felicia, “a pound and a half of weasel curiosity” sent through particle-accelerator tunnels to clear obstructions.

Antimatter falls down, not up: CERN experiment confirms theory

Quigg and Cahn portray early scientists heroically and uncritically — these pioneers might have had great (and sometimes fatal) disregard for health and safety, but their insatiable appetite to explore the unknown was glorious. In their own lives, the authors describe a riot of frantic phone calls, blackboard scribbles and gossip about who had seen what and when as the charm quark was uncovered. As particle-physics experiments grow in complexity and labour force, stories of individual scientists give way to lists of mind-blistering technical achievements. These shifts show how physics has changed — moving down in scale of subject, up in scale of collaboration and into the virtual world in working practice.

Fittingly, the authors experienced the 2012 announcement of the discovery of the Higgs boson while at different laboratories — one in Europe, one in the United States. Neither was at CERN, the European particle-physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, where the announcement was made. They were remote but connected to a global community of particle physicists sharing the extraordinary theoretical and experimental triumph.

Single subatomic particle illuminates mysterious origins of cosmic rays

The book is not a comprehensive history, but one seen through the authors’ eyes, reflecting their points of view and their experiences in US research institutions. There are many other histories and overviews of modern physics (including books by Carlo Rovelli, Sean Carroll and Frank Close), but none, in my view, suffuses personal experience and outlook to such an enriching extent.

The authors’ awe and enthusiasm permeates the text. Their analogies are often poetic, sometimes colourful and occasionally over the top. Lightning “slips down the throat of the sky like a shot of grappa”. Matter made from bosons could be “an insatiable, shrinking, undifferentiated blob”. In likening atomic spectra to music, “chord is perhaps too anodyne a term for the thicket of colored lines”, they write; “better to have in mind the thick unresolved dissonances of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring”.

Cahn and Quigg’s joy at being able to share, and further, understanding of the Universe is catching and their sense of purpose inspiring. Their celebration of the “elegance and economy” of particle physics, of scientific uncertainty and openness, of scientists and the science they explore, leaves the reader in a fever of gratitude. Grace in All Simplicity is an uplifting tale of science and scientific lives well lived.