The creature was the stuff of nightmares. Three-headed, with gnashing teeth that dripped gore and slobbering jaws that foamed poison, his mane and tail sprouted with writhing snakes. So massive that he sprawled across the entirety of his cave, he had a bark that echoed across the realm. His tail was a hissing serpent. By some accounts, his eyes flashed fire. He was so horrific, wrote Hesiod, that he could neither be overcome – or even described.

The monster was Cerberus, and, from the 8th Century BC, he was known to the ancient Greeks, and then to the Romans, as the “hound of Hades”. His job was to ensure that no-one escaped the realm of the dead. (He also protected it from unwanted visitors but, needless to say, this task was required much less often).

More recently, he has also lent his name to a blistering heatwave that engulfed Europe this month.

Large storms, such as hurricanes and typhoons, are given names by weather services around the world to make it easier for meteorologists to communicate information about them. Tropical cyclone monikers are picked from a banal, internationally-agreed rota of everyday names that get recycled every six years – Atlantic tropical storms this year include Emily, Cindy and Sean. Heatwaves, on the other hand, are not.

And attempts to name heatwaves has now led to a growing row among meteorologists about whether it is right to do so.

There is no international convention on naming extreme and excessive heat events, and the current position of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which oversees the naming of storms, is that it might distract attention from the public health threat. It argues that the science of issuing heatwave forecasts and warnings is still too young to be done consistently and effectively.

Yet others disagree, arguing that naming can bring attention to a “grossly underestimated and gravely misunderstood” health threat. And so, as heatwaves – generally defined as periods of unusually hot weather that persist over more than two days – become more common, other organisations are naming them instead. In June 2022, the local authority of Seville, Spain, launched a pilot programme naming heatwaves. The ensuing category three heatwave, named Zoe, scorched southern Spain the following month with temperatures of 43C (109F).

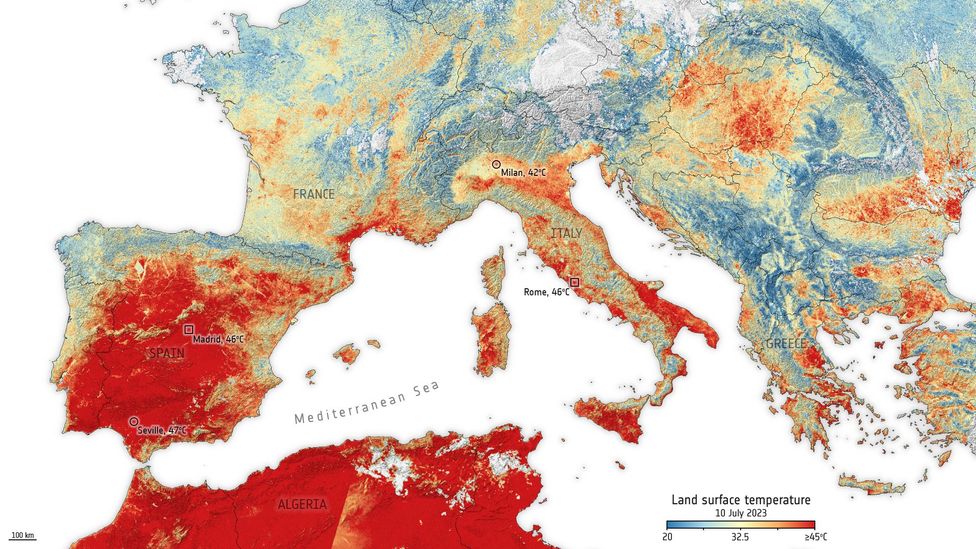

Parts of southern Europe – and in particularly Spain and Italy – have experienced temperatures in excess of 46C (114F) during July (Credit: ESA)

The latest heatwaves, which have affected parts of Italy and southern Europe with temperatures as high as 48.8C (119.8F), were named Cerberus and Caronte – the Italian name for Charon, the boatman of Hades – by an Italian weather website iLMeteo. It has been using mythological figures for the high-pressure regions that produce extreme heat in Europe since 2017.

This year, however, the names seems to have struck a chord with the public worldwide, and led to inaccurate claims the heatwaves had been officially named by the Italian Meteorological Society. The naming of heatwaves was taking place unofficially and “somewhat sensationalistically, in the case of Italy”, the Italian Meteorological Society, told the BBC. A spokesperson confirmed they did not name heatwaves.

You might also like to read:

- What science says about staying cool in a heatwave

- How cities are adapting to a hotter future

- The ancient Chinese way to cool homes

One reason for the reluctance from official weather bodies to name heatwaves is the difficulty in unpicking one event from another. Heatwaves are often not distinct events but can merge into one another and straddle international borders as weather systems build.

“The different levels of heatwave intensity and associated impacts within a heatwave are significant,” adds John Nairns, senior extreme heat advisor at the WMO. “This valuable information cannot afford to compete with multiple names across a single weather system, where one neighbour may have named the event whilst another has not, or multiple names are assigned across the life cycle of an event. We cannot afford to be distracted by additional coordination nor inevitable divisions and distractions which will destroy confidence in forecasts and warnings.”

Yet, the latest mythological names have caught on. And perhaps one reason may be that the names are not simple monikers – they also provide a message.

That approach may be particularly important given that we know that both heatwaves and higher average temperatures overall are far likelier due to human-induced climate change. On 4 July, the world’s average temperature crept above 17C (63F) for the first time in recorded history, while heatwaves are becoming more common and intense. Research has found that the April 2023 heatwave in south-western Europe and north Africa where temperatures exceeded 41C (106F), for example, was 100 times more likely to occur due to global warming.

And the greater risk of heatwaves exerts a heavy toll: a study published this month estimated that 61,672 people died of heat-related causes in Europe in 2022. The authors called on governments to re-evaluate and strengthen heat prevention and adaptation plans.

On the surface, there are some obvious reasons for why the names Cerberus and Charon might fit a heatwave. Both have connotations of hellishness: while Cerberus was the underworld’s guard dog, Charon was the ferryman who took the dead across the river Styx. Meanwhile, the current heatwave, Cerberus, has been divided into three separate, climatic zones – or three “heads” of the monstrous dog.

But there could be a deeper meaning too.

“Cerberus is supposed to be this guardian of the underworld,” says Emma Stafford, professor of Greek culture at the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds. “It’s threatening – potentially life-threatening. And it needs a Herakles to fight it off.”

It isn’t just that Cerberus is monstrous and frightening, or that he keeps doomed souls where they belong. It’s also that it is a creature that is impossible to overpower. Impossible for everyone, that is, except Herakles – the demigod with superhuman strength also often known as Hercules.

And therein lies the hope in the ancient stories – and, perhaps, in ours too. Told to capture and bring Cerberus up from the underworld, Herakles finds he can’t rely on strength alone to overpower the monster.

“He doesn’t just use brute force on it. Instead, he has to persuade or charm the dog,” Stafford says. In other words, Herakles does not just rely on the physical might that have ensured his other victories. Instead, he must use his intellect – much as, perhaps, we cannot fight climate change by simply relying on the same strategies that have brought us here but, many experts say, must come up with a completely new paradigm.

In Greek mythology, Cerberus was a monstrous three-headed dog who was impossible to overpower by all but the demigod Herakles (Credit: Getty Images)

Of course, Cerberus’ and Charon’s literary connections to Hades aren’t a perfect parallel to today’s heatwaves. (Nor is it clear that those behind the naming meant for them to be). For one, the ancients conceived of Hades itself as misty, gloomy, and dark, a far cry from the heat, fire and brimstone of later Christian traditions. (Some media outlets have referred to Cerberus as being named after the Cerberus of Dante’s Inferno, a poem which certainly had much more fire than the original, ancient myths).

The cool temperatures aside, however, there could be other ways in which Hades holds resonance for our heatwaves today. For one, Hades is a kind of nightmarish mirror image of our own world, a bustling community that absorbs, and traps, every single soul of the dead. “Lifeless shadows without body or bones wander about, some jostling in the marketplace, some round the palace of the underworld’s king, while others busy themselves with the trades which they practised in the old days, when they were alive,” writes Ovid in the Metamorphoses.

Hades is, in other words, the “upside-down” of the ancient world – much like the most ominous forecasts of our future under climate change, which seem to be becoming more and more likely to come to pass without a drastic and urgent global response. They predict a kind of “upside-down” for our own world, one in which not only heatwaves but floods, droughts and a decimated natural landscape in some parts of the world become the norm.

For some unlucky souls, Hades also is a place of perpetual punishments. In the Abode of the Accursed, unfortunate souls undergo an eternity of tortures: Tityus, stretched out in chains, must endure vultures always tearing at his entrails. Sisyphus pushes a stone in vain up a hill as it continually rolls back.

In terms of our own fight against climate change, the most poignant victim, may be Ixion – a king punished for murdering his own kin by being lashed to a fiery wheel that spun for eternity, forcing him to run in circles forever, both chasing, and fleeing from, himself.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.