OCTOBER 2022: It’s a cold, foggy morning in the storied Cass Corridor. A faded pagoda-esque structure marks the location of Detroit’s Chinatown, standing just in front of 3177 Cass and a large, one-story gray building with a similarly arched red awning. Under the blanched paint on the opposite side of the building, you can still make out the outline of the word “CHUNG’S,” faded and covered over in parts. The windows are boarded up and the iconic neon signs are long gone. But cracks in the glass bricks and holes that once secured doorknobs allow you a peek into the building and the now-decayed grandeur that was once this legendary Cantonese restaurant—the heart of Detroit’s New Chinatown until it closed in 2000.

On the autumnal morning I visited with a small interdisciplinary research team from the University of Michigan, you could make out a partially caved-in roof and piles of rubble where a grand carpeted dining room used to be. Our group of five—me; three other faculty members from the School of Information, the History Department, and Architecture & Urban Planning; and one of our graduate students—had won a grant to research the evolution of Asian American ethnoburbs in the Detroit Metro area. We were here to visit the former site of the city’s Chinatown and, with it, Chung’s Chinese Restaurant.

I’m an academic from California who moved to the Midwest for a job. Like many of those who are transplants to Southeast Michigan, trying to find community upon my arrival in 2018 proved disorienting. I was used to large, visible, and discrete Asian communities where I could dine and shop for food and produce; to being surrounded by signs in Vietnamese and listening to the numerous dialects and accents of my childhood. Replicating these experiences in Michigan was more difficult. I read dated articles about a “Little Vietnam in Madison Heights,” but when I drove the 40 minutes to find it with my visiting mother, we were met with a mere handful of grocery stores, restaurants, and small shops in disparate strip malls. There wasn’t much community for an outsider like me to embed myself in. It certainly didn’t compare to Little Saigon. Likewise, there was no equivalent Little Tokyo, no Koreatown, or even a 626 Night Market. As I started to find modest Midwestern pockets, the pandemic shutdowns ended those adventures and further contributed to my sense of isolation. Driving through Detroit’s suburbs on those dreary Michigan winter days, I felt incredibly alone—not to mention nostalgic—for the familiar havoc of Orange County’s Viet enclaves.

The members of my research team had varied relationships to the city. Still, there was a shared hunger to learn about how the various Asian communities formed and evolved in the region, and why they eventually moved away from Detroit. But the start of our research revealed inadequacies in our traditional scholarly methods. It felt like we were grasping for data that was disparate and seeking to make connections where they didn’t exist. Attempts to piece together news articles, analyze census data, or examine historical and sociological accounts seemed insufficient on their own.

We’re still figuring this out. At the start of this project, we wanted to know: were the narratives we were familiar with—about segregation, economic depression, the rise in violent crime, the race riots, the murder of Vincent Chin—responsible for the flight of Asians to the suburbs? Forty years after Vincent Chin and during a new rash of attacks against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, we were especially interested in how Asian American communities in Southeast Michigan keep each other safe in the face of racist violence. Had that changed over time? What role did social groups play in sharing information, and how did these networks shape or change their communities? What we hadn’t expected was for a memoir to highlight the importance of Detroit’s Chinatown as the heart of sociality and community for the populations that once flourished in this area. As a researcher, I hadn’t anticipated a subjective narrative to answer these questions in a way that data and archives just couldn’t.

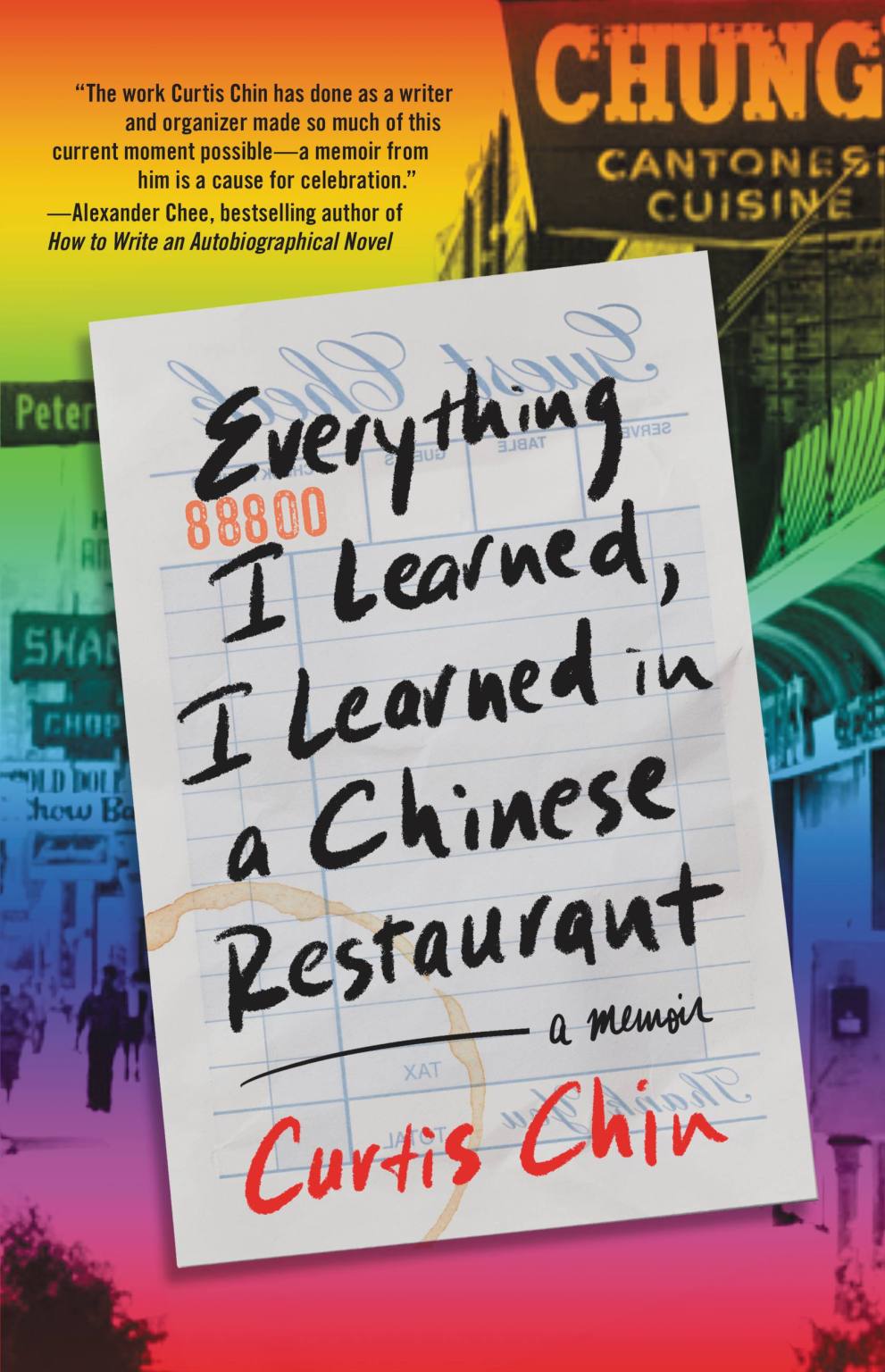

I was lucky, then, that in the process of working on this project I was reintroduced to filmmaker and writer Curtis Chin. Born and raised in Detroit, Chin recalls moving from Detroit to the suburb of Troy and being one of the few Asian kids in school there (today, the city has an Asian population of about 27 percent, making it the largest Asian American population in the state). For Chin, the famous Chung’s Cantonese Restaurant became a vital site of identity formation. So much of Detroit for him, and by extension the larger community, was understood from the booths of that dining room.

Chin’s new memoir, Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant, draws a picture of a family restaurant divided into the chaotic family domain of the kitchen where Chin ran rampant as a child and a bustling red-and-gold dining room adorned with Chinese antiquities. Patronized by the city’s elite, the neighborhood regulars, and the corridor’s dispossessed, the dining room emerges as a destination for adventure and excitement: it’s certainly where Chin and his siblings mingled and learned about people from the greater world. Detroit is the backdrop—a city robust in character and history, but also one in slow, steady decline.

As an author, Chin had a clear goal. “I’m not trying to write something nobody else has written before,” he explained. “I just tried to write a book that was true to my life experience. I know that typically books are written about the East Coast and the West Coast and that the Midwest experience is different.” I’m the daughter of immigrants and refugees from Vietnam. I grew up in the waiting area of my mother’s nail salons. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I felt a certain affinity for young Curtis, who grew up—at least, in the ways that really matter—in the kitchen and dining room of Chung’s Chinese restaurant. Like Curtis’s father, Big Al (so nicknamed “for his girth”), my mother encouraged me to interact with her clients, to ask questions, to learn things that she wouldn’t know to teach me. I still remember the embarrassment of being encouraged by my mom to sell holiday wrapping paper for our school’s fundraiser to her clients.

Unlike the gregarious Curtis, I was introverted and soft-spoken. Still, Chin remembers mortifying scenes in which Big Al pushed him to speak to Mayor Coleman Young—moments of growth that would later prove invaluable to the adult to come. It was the same for me. Being forced to put ourselves out there in these racially coded commercial spaces prepared us both to take personal and professional risks that led us to major moves, geographic and otherwise. We developed skills for getting over feelings of shame or unease. These days, we can find our way anywhere.

Chin calls himself the family’s “riot baby” because he was conceived during Detroit’s 1967 uprising (by that token, I’m the family refugee-camp baby). Most of the book captures the restaurant as a bustling place of business and sociality. It ends with his departure from the city as a newly minted graduate of the University of Michigan. All throughout, the restaurant grounds readers, offering a vivid entry point into the history of Detroit. The book’s pages resurrect the shell of a building we encountered on that October morning, transforming it into a welcoming melting pot that—despite all odds—persevered as the population declined and the Cass Corridor fell into disrepair. At the start of the book, Chin exhibits immense, palpable pride for the grand and thriving business. He describes the incomparable dining room as “the happiest place on earth.” It’s here that Chin was educated by his family, an ever-changing lineup of Chinese cooks and staff, and the colorful residents of the Corridor.

As Serena Maria Daniels and Maximilian de la Garza wrote in a 2016 article for the Detroit Metro Times, “If you asked most Detroiters what they thought of this run-down part of town, they would have probably mentioned the storied Cass Corridor, wrought with hookers, hustlers, and drug addicts.” Today, though, the Cass Corridor is seeing a fraught revitalization. For decades, it served as a cautionary tale, a red-light district of sorts. Of course, that narrative effaces the vibrant lives, the creative community, and the businesses that prospered and made Detroit the city that it is (or was). By contrast, Chin can be brutally honest. He doesn’t shy away from the seediness of the area or his grandmother’s abuse, nor does he gloss over the embarrassing encounters that represented hallmarks for his budding sexuality. He names the racism and the economic disparity he sees around him. And he reveals the ugly traumas that occur in the tight households and businesses of multigenerational families. But he is also tender and, at times, unsure. He is careful to honor the labor and the sacrifices made on his behalf. Read together with recent reporting of real estate sales, new developments, contentious demolitions, and demographic changes, Chin’s account provides a unique portrait of a neighborhood in constant flux.

Numerous questions underlie Chin’s telling, many of them common among memoirs. How much can he trust his own memories? How much have his recollections been colored by the years that followed? To whom is he, as a storyteller, responsible? There are no easy answers, and the narrative intersects with a maelstrom of additionally complex subject matter: multigenerational Asian American homes, the drama of family-run businesses, Detroit in the latter part of the 20th century, and coming of age as a queer Chinese American boy. As if that weren’t enough, Chin also writes for a diverse audience, ranging from his own family to those completely unfamiliar with the setting and historical moment, even to other Asian Americanists who may hold him to account.

A significant moment for Asian American history took place in Detroit in 1982, when young Chinese American draftsman Vincent Chin was brutally slain by two white men on the eve of his wedding. The subsequent trial resulted in a shockingly light sentence for the murderers—one that spurred a national Asian American civil rights movement. This moment figures prominently in Chin’s book. Yet Chin offers a different, more intimate retelling than most Asian Americanists will be familiar with: the straightforward, personal recollections of a 14-year-old child. The soon-to-be teenager clearly knew something was going on, but the gravity of the situation was then unclear. Vincent Chin was simply “one of the cool Asian guys who were buddies with some of our younger waiters and managers.” We see the seeds of the activist Curtis Chin would later become, but that political understanding is nascent. For the most part, he provides the reader with the bare, unembellished facts as he knew them then; he refrains from interjecting the knowledge and understanding that he develops later. Indeed, Chin’s understanding seems to be continuously developing. Even in dialogue, he checked his own knowledge against that of our research team, both humble and almost unwilling to trust his memory.

When I spoke to Chin about his book in July, nearly six months after my research team interviewed him, the writer told me, “As a young kid at that time, I heard about stuff after the fact … Specifically, that schism between the […] working-class Asian Americans and the college-educated ones that did eventually take over [the activist movement].” For Chin, the nuances of the sociopolitical order in Detroit’s Chinatown didn’t feel appropriate as part of a memoir for a general audience. In conversation, however, he proves very aware of not only that ecosystem but also where he fits into it. “I’m torn,” he told me, “because I am one of those people that straddles both [conflicting] groups” who were at odds during the post–Vincent Chin murder protests. He explains:

My family is working-class, but at the same time I did go get a college degree. So, I understand that. And I can understand the problems of the Chinatown community. Because it was a very patriarchal society. It was all Chinese men chomping on their cigars. And I could see why the more progressive college-educated set might not want to deal with that, might not want to work with that way of leadership.

Chin’s assertion that “Vincent wasn’t the first person I knew who was murdered, nor would he be the last” is perhaps the book’s most shocking line for me. In writing, his attitude toward violent loss appears almost casual. Yes, the city has long been depicted as riddled with crime and violence. Chin himself mentions numerous deaths, murders, and catastrophic fires, as well as the gradual disappearance of familiar faces, which, in its mundanity, assumes a profound sadness. Still, there is also recognition of the potential weight of these moments, of incidents that accumulate over time and serve as reasons for entire communities to slowly move out of Detroit and into safer, more geographically dispersed environs. Chin is unnervingly candid about his own family’s precarity: “It didn’t matter that we were model citizens or that our restaurant was on all the ‘Best of Detroit’ lists. We were vulnerable.”

This growing sense of vulnerability and otherness only heightens as Chin grows into his queer identity. The writer grew up gay and Chinese in the 1980s, at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. His only knowledge of queerness at the time was the illicit sex trade of the Cass Corridor and the alarmist and worrisome news coverage of the day. Set against this backdrop, Chin’s sexual awakening and excitement are tangled with feelings of self-loathing, and even desperation—especially where his sexuality intersected with his racial and working-class identities. He writes, “I knew whatever I said or did would reflect not just on me or my family or the other Asian kids at my school but on every Asian on the planet. Now I was like almost everyone else who came down to the Corridor: a pervert.” This shame and despair, not to mention the need to keep it secret for fear of expulsion from his family and the potential torture of “dying alone,” resonates painfully.

“In some ways,” Chin stated in an interview, “my coming out or my journey isn’t just about my memoir, but it becomes my family’s memoir in some ways, too.” Both Chin’s racial and sexual identities are complicated by his feelings of responsibility to his family. In conversation, Chin discussed how family “becomes a bigger issue when you’re trying to come out, when we’re trying to become our own person. They play an outsized role. They’re not always just the adversary.”

It is clear that Chin has grappled with these dynamics for much of his life. Evidently, he has always felt tied to this city and its constituent communities. He has also felt othered and enjoyed the freedom to come and go. Still, he wears his multiple identities with charming conviction and uses them to reflect on his relationship to and understanding of the city, the Asian American community of Detroit, and his own family. Ultimately, he exhibits overwhelming respect for his parents, who in many ways stand out for their unconventional parenting. He explains:

When you’re a kid, a lot of parents tell you not to talk to strangers, but my parents told me the exact opposite. They wanted us to talk to strangers, and who they were referring to were the people in our dining room. Because my mother didn’t graduate from high school, my dad only went to community college for two semesters, they didn’t know what opportunities existed outside the four walls of Chung’s, but they knew that we had a dining room full of people who could help us access that.

He called the experience “magical,” telling me toward the end of our interview: “That’s the gift my parents gave me. And that the restaurant gave me. It prepared me for the life that I currently have.”

Chin continuously confronts questions of home. He invoked the opening line of the book in our conversation: “Welcome to Chung’s. Is this for here or to go?” He added, “I’ve spent a lot of my recent life on the go. I’ve gone to over 600 places in 20 countries now giving talks. I’m constantly living out of the airport and doing laundry on the road.”

As someone who only lived in Southeast Michigan temporarily, aspects of the city will always be unknowable to me. No number of historic tours, books, museum visits, or conferences will ever enable me to understand the city in the way that Curtis Chin does. It’s likely impossible to capture that level of understanding in words or on the page. Still, Chin’s book provides an approximation. Reading it, I felt like I was finally beginning to grasp this unique American city—why Asian Americans were drawn here, why they left, why some remain or return.

Towards the end of our call, I observed a moment of hesitation in Chin. He was thinking about the turbulent past of the city—about his own history, so wrapped up in it—and while acknowledging my weird position in reading his book, interviewing him, and writing this piece, he asked, “Am I a real Detroiter anymore?” After a beat, he went on: “That Detroit version of myself is one that started it all. It’s where I learned all my values and who I am as a person, and it’s how I’ve navigated life as a Detroiter, as a Midwesterner.”

The words were bolstered by an audible sense of surety. I kind of envy him that. I’m still not sure about my relationship to the city, and if I can (or ever will) find my people or community there. I may never know: after five years in Michigan, I’ve since relocated to New York for another academic job. It doesn’t matter. Detroit leaves its mark on you regardless.

¤

Anne Cong-Huyen is an academic librarian and scholar of Asian American studies and digital humanities.