Metaphors can provide insight into a problem or situation by taking what we know about one thing and using that to shape our understanding of another.

For example, my colleague Paul Thibodeau studied how using a metaphor comparing crime to a virus leads to different potential solutions than using a metaphor comparing crime to a beast. Although crime itself does not change, the aspects of crime we focus on vary depending on the metaphor we use to understand it.

Together Alone

I was reminded of Thibodeau’s work when speaking to a high school teacher about their students. The students spend a great deal of time socializing—they text, cruise social media, and gossip, talk, and fight with their peers all day. Nonetheless, they seemed fundamentally unhappy, isolated, and just plain lonely.

Ironically, they aren’t alone in feeling alone. In 2023, the US Surgeon General issued a report titled “Our Epidemic of Isolation and Loneliness.” This report documents the lack of connection many people, including teenagers, feel. Only 39 percent of adults feel very connected to others, meaning 61 percent do not. It reports that social engagement with friends dropped 66 percent from 2003 to 2020, a precipitous drop that began in 2012, not during the pandemic. Social engagement dropped an average of 10 hours a month during this same period. This is also the timeframe following the widespread introduction of cell phones that anxiety and depression among adolescents began to peak.

These decreases in social engagement affect not just mood and mood disorders, although those outcomes are important unto themselves. They also have important effects on physical health, including vulnerability to illness, heart disease, and stroke.

The Metaphor of Social Malnutrition

More than half of US adults report feeling lonely, with the highest rates among young adults. Although the Surgeon General’s report focused on time spent alone, the teacher I spoke to saw a different problem among students, something they called social malnutrition. The students spent all their time interacting with others. The quality of their time, however, was exceedingly low. They didn’t seem to talk about their hobbies or laugh about shared books or memes or movies. They didn’t share their thoughts or feelings, at least not in the intimate way that is often seen as one of the developmental milestones of adolescence.

It was as if they spent their days eating junk food but never gave their bodies the kind of food it needed to grow and thrive. They weren’t hungry, they were malnourished. The malnutrition metaphor is telling. Historically, malnutrition was associated with food scarcity—one ate what one could and, in conditions of insufficient food or food quality, one became malnourished. But one can also become malnourished by eating the wrong food. A diet of junk food leads both to obesity and malnutrition. That, the teacher said, seemed to be what the students were experiencing.

Socializing without intimacy, support, or intellectual content may lead to feeling full, overwhelmed, and overstimulated and still unsatisfied. Maslow argued that connectedness, love, and belonging are core human needs. They may not be ones easily fulfilled by scrolling, likes, and insults. Those may make great desserts but not the main course.

Metaphor as Research Catalyst

As a long-time researcher into adolescent social interactions, I was struck by how the metaphor of social malnutrition spurred research ideas I had never considered before. Nutritionists study and set recommended daily requirements for vitamins, minerals, calories, carbs, and other basic components of our diets. We judge malnutrition against those baselines. Researchers have no such standards, to my knowledge, of what minimal requirement of the quantity (calories, in our metaphor) or quality (vitamins, minerals, and other components) of social interactions people need to be healthy. We do know that having just one friend is tremendously beneficial for teens. The difference between none and one is huge. Researchers have studied the association of different relationship qualities that predict well-being for decades. This was my master’s thesis, and I wasn’t breaking new ground.

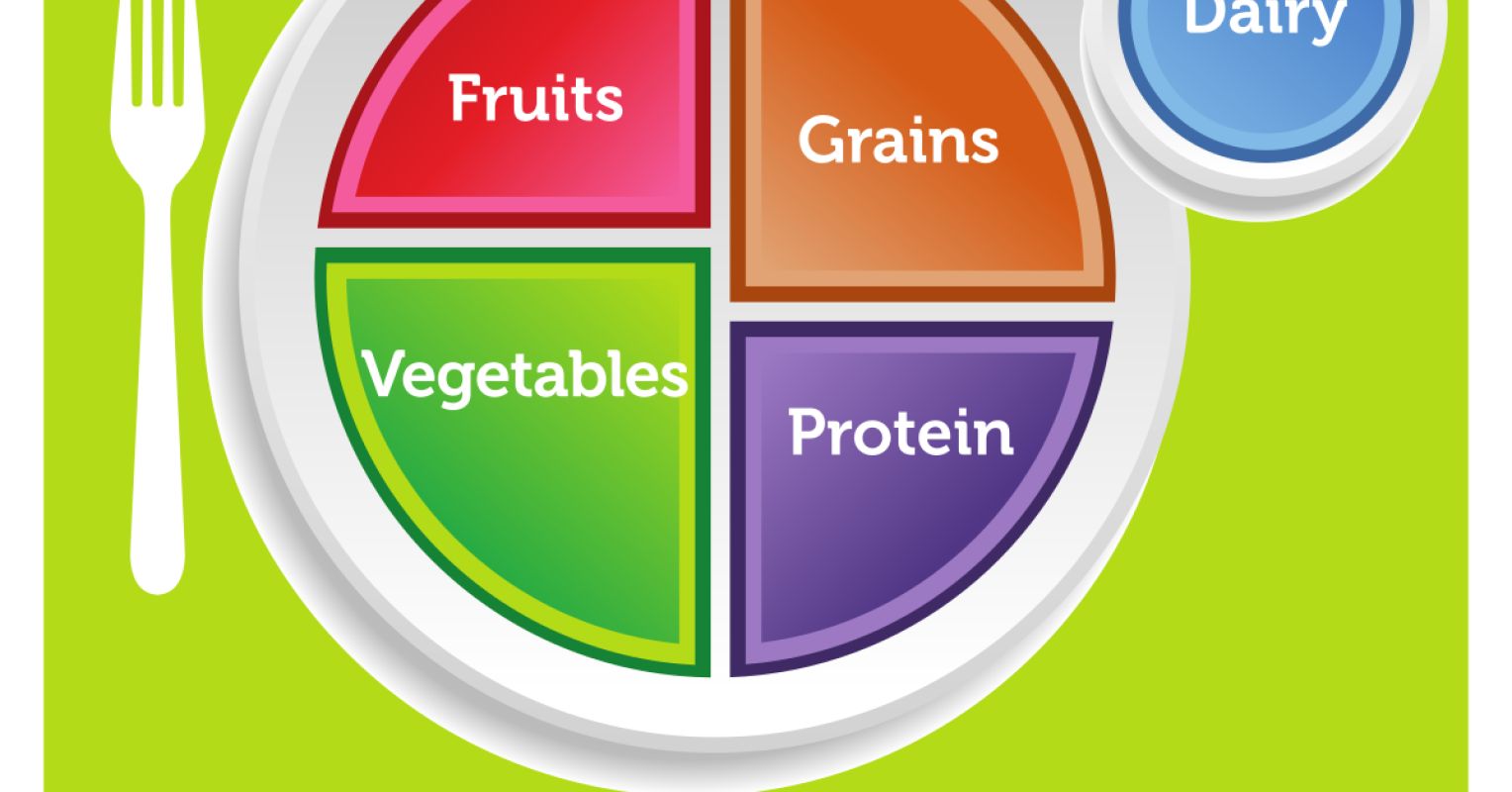

Thinking about it as one does nutrition changes the emphasis from that of individual relationships to the whole panorama of social interactions. How would one go about developing a food pyramid or “plate” to describe the mix of experiences most people, of different ages and perhaps temperaments, need? It’s not about where you interact; many people find meaningful and close relationships online, and many don’t in person. But the nutrition metaphor suggests new approaches to the problem.