Seven years ago, when Riley Lipschitz was finishing her medical residency and preparing to move back to her home state of Arkansas, finding a book club was high on her list of priorities. “When you’re an adult, it’s hard to build relationships,” she says. “And I knew out of the gate that I wanted to try to find a book club because I would meet people who are different from me.”

Lipschitz had been in a book club in medical school, and she was hoping to find one in Arkansas that would help her break out of her doctor bubble. She put out a call on Facebook and was directed to a friend of an acquaintance who was running a book club. “They invited me to join, and of course, I clamored [to do it],” she says. “I’m very overzealous about it. And had been doing it for the last seven years with the same little crew of women.”

Lipschitz’s new book club meets once every six weeks or so, and the participants range in age from 30 to 50. Lipschitz is the only physician, exactly as she hoped. Soon, their group will be holding a joint meeting with her mother’s book club, a more structured get-together that requires RSVPs a full month in advance. “I was just chatting with my mom about the [current] book today,” she says. “And my mom had dug into all this history, and I was like, ‘Damn, I didn’t do any of that.’ So, I better get my s–t together for this much more organized 70-year-old-lady book club.”

According to BookBrowse, in 2015 five million Americans were involved in a book club of some kind. In 2023, it would be no surprise if this number has only grown with the rise of BookTok and Bookstagram, where creating a community with fellow readers is easier than ever. Subsequent BookBrowse research found that the majority of participants in private book clubs were women (88 percent of private book clubs were made up of all women), but at least half of public clubs tended to include men.

Like Lipschitz, when I moved from one state to another without knowing anyone, I immediately joined a book club formed around a true-crime podcast that brought me my first and oldest friend in my no-longer-new town. What I didn’t know then was that book clubs were part of a grand tradition.

Let’s take things back to the first verified book club in North America. As the first printed books in Europe and China were religious texts, the earliest recorded North American book club was more or less a Bible study group. Anne Hutchinson began a scripture reading circle in 1634 during her boat ride from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. When her club became more popular than the official local church services, she was exiled from the colony entirely.

Over the next century, book clubs grew increasingly common among middle- and upper-class Europeans, and wealthy colonists adopted the trend in North America. There were as many as a thousand private book clubs in 18th-century England, where people drank, gossiped, and/or discussed radical politics, in addition to the infamous French salons. The French salons were decidedly upper-class gatherings, usually organized by prominent society women, where writers, aristocrats, and artists gathered to talk literature, politics, and philosophy.

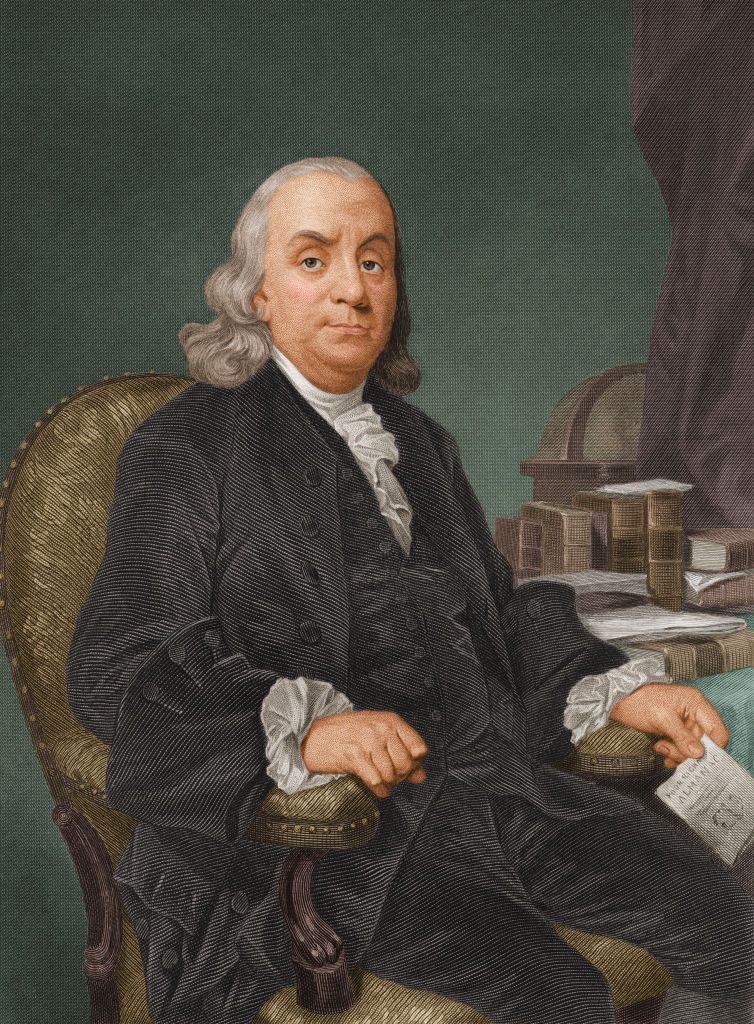

Plenty of early American book clubs, like Benjamin Franklin’s Junto club, formed around the same time. Franklin’s club was much more formal than most of today’s book clubs. Members elected officers, were required to write essays on serious topics, and answered a strict set of preestablished questions (though they did eat and drink at the local pub during meetings).

Hannah Adams, the first woman to make a living writing in the U.S., was also in a book club in the 1700s, and there were a few other groups for women in the mix. But reading circles really grew in popularity in North America in the 19th century when American women began meeting to expand their knowledge and question their purpose, long before they were allowed to be officially educated. Hundreds of reading circles popped up in response, such as journalist Margaret Fuller’s Conversations, one of the most famous of these groups, in which women openly asked one another, “What were we born to do? How shall we do it?” while comparing their educational prospects to those of the men they knew. Some of the groups were explicitly born from exclusion: One of the more famous clubs of the era, Sorosis, was formed after women journalists were barred from an event where Charles Dickens was speaking.

The book groups didn’t necessarily look alike. Middle-aged women married to middle- and upper-class men had the most time and freedom to enjoy these clubs, but working-class women made their own circles as well. One group of millworkers made time to talk about literature while they worked. These book clubs debated the merits of studying the natural sciences versus art, whether or not Socrates was justified in his suicide, white privilege (“Which has the white man most injured, the Indian or the African?” was the topic of one 19th-century meeting), politics, economics, and of course gender roles. But it wasn’t just talk. They were all engaged in “critical thought, civic discourse, and cultural production,” as historian Mary Kelley put it. The clubs were intent on developing both the minds of their members and their communities at large.

Some clubs ran literary magazines, built libraries, and sponsored speaking groups. Once universities began allowing women to study (a slow process that began with Oberlin College in 1837), some book clubs funded scholarships and established trade schools for women. Members advocated for the integration of kindergarten into the public school system and ran them until the state would step in. “The usual method is for the club to assume the responsibility and expense of the experiment, and to carry it on until the authorities recognize its value and adopt it,” wrote May Alden Ward in 1906. Some 19th-century women’s clubs, like the Ladies’ Literary Club of Ypsilanti, are even still going.

While white women were the first marginalized group to be able to use book clubs for education and empowerment, book clubs have also been havens for other marginalized Americans for hundreds of years.

The first reading circle for Black men was formed in 1821 in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1827, Black women in Lynn, Massachusetts, founded the Society of Young Ladies, a reading club that was soon emulated across the northeastern U.S. Meanwhile, in states that still allowed slavery, enslaved people could be violently punished for being literate, and anyone who was caught teaching them could be imprisoned.

Even so, Black book clubs built libraries and sponsored abolitionist speakers, and their readings and conversations mobilized many of their own members against slavery. Sarah Mapps Douglass, an early Black feminist and abolitionist, helped found the Female Literary Society in Philadelphia in the 1830s while she was in her 20s, and it was her conversations in the club that led her to feel that “the cause of the slave [is now] my own.” Members of the Female Literary Society wrote original essays that they submitted to one another for critique and, eventually, to William Lloyd Garrison for publication in his abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

Queer Americans in the 20th century likewise established societies that offered safe communities and libraries to house collections of LGBTQ+ writing, some of which also still exist.

Even though 19th-century book clubs allowed women to take one another seriously in a society that devalued their intellectual contributions, some people still write off today’s book clubs as groups of gossipy women drinking rather than instilling real change or becoming a space for challenging conversations. When the Book of the Month Club was founded in 1926, some people were convinced it would unforgivably “dumb down” American reading. Infamously, Jonathan Franzen got flack for worrying that having one of his books in Oprah’s Book Club would make him seem middlebrow. When one 19th-century woman told her father that she and some friends were starting a literary club to discuss Milton and Shakespeare, he called it “harmless,” dismissing her circle’s potential to do much at all. Her mother noted that it sounded like “women’s rights.” At times, people can be dismissive of any interest deemed too feminine, and women make up 80 percent of fiction buyers. So, while it’s true that book clubs are about community building and socializing as much as anything else, they aren’t classes. And they aren’t meant to be. It’s even okay that some book clubs value entertaining books over literary or nonfiction works, but that doesn’t mean women are reading frivolously. As writer and editor Lucy Shoals notes in a review of English professor Helen Taylor’s work Why Women Read Fiction, not only are women buying more books, but “more women than men are members of libraries and book clubs. Women make up the majority of the audiences at literary festivals and bookshop events. They listen to more audiobooks and attend more literary evening classes. Most literary bloggers are women.”

Lipschitz had hoped that her book club would be a break from the demanding reading she did as a physician. Going in, she told the new crew she didn’t want to read any nonfiction. She wanted a space for “emotional learning” since she was already “having to learn so much technically to learn to be a doctor,” and she found it. But as the group grew close enough to take on difficult topics, they read Educated by Tara Westover, Stay True by Hua Hsu, and White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, and those nonfiction books sparked some of Lipschitz’s favorite conversations in the group. They talk about race and politics consistently, bringing their experience as mothers, educators, doctors, government officials, and lawyers into the conversation. “Most of us are working women. Most of us are mothers,” she says. “And it’s, like, themes around feminism, contemporary history, politics. What does the future for our children look like? These bigger themes inevitably come out in all our discussions, which is cool because it’s not contrived.” Lipschitz also hates being disappointed by prose, so she’s helped push the book club toward literary work when they do read fiction.

That trend mirrors more of BookBrowse’s research. Most book clubs — 70 percent of them — read fiction. “But they aren’t the bastions of ‘women’s fiction’ that some believe them to be,” wrote Davina Morgan-Witts, the publisher of BookBrowse. “For example, 93 percent read nonfiction at least occasionally, and the longer a book club has been together, the broader its selections tend to be.” Their research found that the vast majority of people, or “91 percent of book club members, say that they value being exposed to books that they otherwise wouldn’t have read.”

These days, book clubs are run by everyone from private individuals and library employees to professional societies and celebrities like Oprah, Reese Witherspoon, Emma Watson, and others. Celebrity groups have gotten popular books reprinted due to sheer demand. Substack has also become a home to extremely popular book clubs, like Roxane Gay’s the Audacious Book Club. Content creators on Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok are building audiences of tens of thousands and reading books with their followers. While nothing truly beats meeting in person, virtual spaces offer readers the opportunity to create connections with people all over the world and chat with bibliophiles who share their specific interests or struggles. Want to join a book club focused on classics? Thrillers? Health and wellness? Romance? Queer romance? Queer YA romance? The options for specificity are nearly endless and not always frivolous.

Book clubs still have the power to spark change. Triciah Claxton and Alanna Ramirez first bonded over books in the second grade in the Bronx. Now in their 30s, the pair fondly remember spending time together in the school library and chatting about Beverly Cleary and Sweet Valley High after church. As they grew up, the two remained close friends, but books took a backseat to conversations about jobs and families, though Claxton made sure to read at least a page or two of something she enjoyed every day, all the way through law school and the bar exam. And then came the pandemic. All of the sudden, Claxton and Ramirez were calling each other and chatting about books again, just like when they were kids. “It kind of came back around, and we started sharing what books we’re reading and decided to open it up to our sister girl group,” Claxton, now an immigration attorney and mother of three, says. They soon collected a half dozen close friends to read together through quarantine, though Ramirez admits the first book wasn’t a hit.

Nevertheless, the persistence paid off. Their casual pandemic meetings became a Bookstagram called Loc’d & Lit, and their virtual book club grew to include thousands. That spawned a podcast and a second book club when they felt it was safe to meet in person. Just like the 19th-century reading circles, Loc’d & Lit is already publishing its own reviews, hosting local readings, and fighting for change in its community.

Eventually, the pair’s affection for their growing literary community pushed their focus outward. Both have been glad to see the publishing world evolve, making space for more people of color. For Claxton, having her sons reflected in their books in a way she never felt as a child was life-changing. “My son loves the Percy Jackson series and Greek mythology,” she says. “But then he read Children of Blood and Bone and started learning about all the African gods and goddesses and the Orisha. It’s like a whole world opened up for him, and I was really glad to see that.” But when they learned that less than a third of Bronx third graders were reading at grade level even before the pandemic and that the borough had only a single bookstore, Ramirez and Claxton were spurred to action. “We know that the government uses the third-grade testing as future projections for jobs or jail cells,” Ramirez says. They founded a literacy organization and built a business plan for a local bookstore that will prominently feature Black writers, thanks to their renewed love of reading sparked by a pandemic book club. As Ramirez says, “With greater knowledge comes greater responsibility.”

The options for finding your own reading circle and potentially changing your own community are, beautifully, nearly endless. Check in with your local library, your favorite bookstore, or head to Meetup or Bookclubs.com to sort online and find local groups by topic or proximity. Happy reading!

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY