Abstract

How to prevent and resolve COVID-19 pandemic and similar public health crisis is a significant research topic. Although research on science literacy has been involved in dealing with public health crisis, there is a lack of empirical tests between the mass public’s science literacy and co-production during COVID-19 pandemic. With the empirical evidence from 140 cities in China, the study finds that the public’s science literacy significantly promotes co-production in the battle against pandemic. Specifically, for every 1% increase in the mass public’s science literacy in the city, co-production increased by 14.2%. Meanwhile, regional education level and local government capacity can expand the positive role of the public’s science literacy on co-production to fight against COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the performance of the public’s science literacy on co-production against pandemic shows heterogeneity at different stages of pandemic prevention, in different regions, and in cities of different scales. This study complemented the gaps in existing research on science literacy and co-production and empirically verified the potential positive role of the public’s science literacy in pandemic prevention and control. Furthermore, it provided new ideas for improving the effectiveness of public co-production in public health crisis governance.

Introduction

The history of human civilization is also a history of struggle against diseases (McNeill, 1976; Sigerist, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic, which outbroke in December 2019, is the most severe health and economic crisis that humanity has faced in a century, causing serious harm to human life and health as well as social development (Guterres, 2020). In the war against the pandemic, public participation has been significantly enhanced, with public co-production such as lockdown, social distancing, mask wearing, and vaccine administration being thoroughly demonstrated to help prevent the spread of the pandemic and mitigate its societal and economic impacts. The effectiveness of public health policies lies entirely in the large-scale and voluntary cooperation of the public (Li, 2020). Co-production was defined as “the critical mix of activities that service agents and citizens contribute to the provision of public services” (Brudney and England, 1983), but scholars tend to recognize the diversity of the concept due to the ambiguity of the concept of co-production. In this paper, we define the collective efforts by the public and the governments in the fight against novel corona viruses as a specific type of co-production in the context of a pandemic crisis (Zhao and Wu, 2020).

So far, scholars have analyzed public co-production efforts in the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic from two perspectives: environmental factors and individual factors (Voorberg et al., 2015; Alonso et al., 2019). Existing research has addressed individual factors such as individualism (Huang et al., 2022), anti-intellectualism (Merkley and Loewen, 2021), and scientific skepticism (Brzezinski et al., 2021), but attention to the variable of science literacy is still limited. The OECD defines science literacy as the “ability to engage with science-related issues,” implying that science literacy is not simply knowledge, but rather “the kind of knowledge which can be used to solve practical problems such as health and survival” (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2016). The science literacy is widely recognized as the foundation of humanity’s response to global challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Valladares, 2021). Faced with the unknown novel corona virus, the public’s efforts to prevent the spread of the virus require a certain level of scientific knowledge, scientific spirit, or scientific trust, whether it was for the protection of personal health or to maintain public interest by stopping the virus from spreading on a larger scale. These efforts include voluntarily wearing masks, getting vaccinated, practicing good personal hygiene, maintaining social distancing, and complying with health monitoring and self-isolation requirements, all of which help to block the transmission of the virus and formed the greatest force to combat the pandemic alongside the government. So, the public is not merely a passive follower of pandemic prevention policies or a simple consumer of public services, but a co-producer with an active awareness, working together to provide public services (Zhao and Wu, 2020). Although countries worldwide emphasize the importance of fostering science literacy during the COVID-19 pandemic and are actively promoting science popularization (Shao et al., 2020), the empirical verification of the relationship between public’s science literacy and co-production in the pandemic is still lacking.

After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese populace collaborated extensively with the government, supporting and expanding official efforts by undertaking grassroots emergency tasks. This included the transportation and provision of food, masks, and medicines, as well as providing logistical support for frontline healthcare workers (Su, 2020). Simultaneously, the ideological beliefs and partisan biases of the Chinese population do not show significant differentiation in individual-oriented motivations (Kahan et al., 2011; Lewandowsky and Oberauer, 2016). There is no inherent inclination to reject science and expert consensus. In view of this, this study intends to empirically test the relationship between the public’s science literacy and co-production against the pandemic based on empirical cases in China, using data from the 2020 national survey data of both civic science literacy by China Association for Science and Technology and co-production during the COVID-19 Pandemic by Baidu Index (the official data of China’s largest search engine) where the search number of keywords related to the public’s co-production during the period from 27 December 2019 to 28 April 2020, in 140 cities was collected. In addition, the study further explores the potential impact of regional education level and local government capacity on the relationship between science literacy and co-production, providing new ideas to improve the effectiveness of public participation in public health crisis governance.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the second part comprises a literature review and research hypotheses; the third part outlines the research methodology, employing econometric methods to construct a research model for hypothesis testing; the fourth part presents the research findings, conducting a detailed analysis of the results; and finally, the last section offers discussion and conclusions.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Mass public’s science literacy and co-production during the COVID-19 pandemic

Science literacy enables individuals to comprehend scientific processes and practices, familiarize themselves with how science and scientists operate, weigh and assess the products of science, and possess the capability to engage in citizen decision-making related to scientific values. While science literacy has traditionally been perceived as an individual trait, individuals are nested within communities and society. This implies that science literacy is beneficial not only for individuals but also for the health and well-being of communities and society at large. Existing literature generally agrees that trust in science (Sturgis et al., 2021), scientific spirit (Rutjens et al., 2018), and scientific knowledge (McPhetres et al., 2019) can help the public better cope with the challenges posed by major sustainable development issues such as—climate change, energy transition, science and technology innovation, biomedicine, and green development. The COVID-19 pandemic as a global public health crisis, like the aforementioned issues, is characterized by technical complexity, cutting-edge issues, and expertize. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic requires the use of multidisciplinary knowledge from the fields of medicine, biology, and epidemiology (Wang. and Liang, 2020). Individuals with higher science literacy (Motoki et al., 2021), greater trust in science (Stosic et al., 2021), and a more extensive understanding of knowledge (Zhong et al., 2020) related to the novel corona virus are better equipped to comprehend the principles of science and logics of action behind pandemic prevention policies. They are more likely to adopt a proactive stance in adhering to measures such as maintaining social distance, wearing masks (He et al., 2021), and getting vaccinated (Karlsson et al., 2021). In contrast, if the public complies with epidemic prevention measures only under pressure, there is a greater likelihood of experiencing resistance and exhibiting non-compliant behavior (Brzezinski et al., 2020). Belief in science influences physical distancing (Brzezinski et al., 2021) and policy compliance (Brzezinski et al., 2021) when dealing with COVID-19 lockdown measures, subsequently impacting the societal governance costs.

The above-mentioned research has preliminarily focused on the relationship between mass public’s science literacy and co-production responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, but there are still many apparent shortcomings. On the one hand, these studies utilized indicators for measuring science literacy that may be somewhat one-sided, and the sample scope has certain limitations, failing to adequately reflect the science literacy possessed by individuals and society. On the other hand, they primarily employed subjective indicators for assessing co-production behaviors in pandemic prevention, making it challenging to determine whether public co-production was a voluntary act. Existing research increasingly relies on online behavioral indicators to address this deficiency (Wu et al., 2022; Bonsón et al., 2019; Chatfield and Reddick, 2018). In 1992, China established the system of sampling surveys on civic scientific literacy, conducting surveys roughly every two years. As of 2023, 12 nationwide surveys have been carried out, encompassing citizens aged from 18 to 69 on the Chinese mainland. The survey questionnaire is regularly updated to keep pace with the development of the times, enabling a more comprehensive reflection of the actual science literacy status of the public. Furthermore, China’s Internet penetration rate has exceeded 70%, and participation in public affairs through the Internet has become increasingly common, which provides an objective basis for this study to use netizen’s search behavior data (Baidu Index) to measure public co-production against the pandemic. Based on Chinese data and cases, we can examine the relationship between mass public’s science literacy and co-production in pandemic prevention and control at the national level to address existing knowledge gaps.

Thus, the first hypothesis of this paper is as follows:

H1: The public’s science literacy significantly promotes co-production in the battle against pandemic.

Environmental factors influencing mass public’s science literacy and co-production

While discussing the role of mass public’s science literacy in co-production for pandemic prevention and control is essential, the relationship between them may vary due to different environmental contexts. Regional education level refers to the development of education within a certain region, mainly including the level of educational opportunities, educational inputs and educational equity. Some scholars have defined government capacity as the ability of the central government and its bureaucracy to infiltrate society and allocate social resources to achieve its established goals (Besley and Persson, 2009; Mann, 1984). Education is an important determinant of individual quality, and government capacity affects the effectiveness of regional governance, both of which may affect co-production during the COVID-19 pandemic. With this in mind, we will explore the potential moderating influences of regional education level and local government capacity.

Regional education level

In China, the educational level varies greatly from region to region. Education is considered a crucial predictor of civic engagement in public affairs (Egerton, 2002), and the level of education also has a significant impact on co-production., and some studies have given empirical experience and evidence. Sundeen demonstrated that people who had received more education than high school were more aware of community needs and were more able to articulate their own needs (Sundeen, 1988). They also possess the administrative skills to participate in public affairs (Voorberg et al., 2015). Thomsen argues that the skills and knowledge of the public are crucial to the extent of their contribution to co-production (Thomsen, 2017).

Further, Parrado et al. (2013) and Alford and Yates (2016) considered individuals’ educational level a crucial demographic factor in their research on influencing factors in co-production in three public service fields—namely, safety, environment, and health. Although their study found a weak relationship between the public’s educational level and co-production, this study tries to give different explanations based on the literature combing: (1) The era context of the study seriously restricts the reliability and validity of the findings. The aforementioned survey only covered the traditional forms of co-production, such as neighborhood help and household waste recycling. With the rapid development of information technology, the interactive mode created by new media can significantly improve the frequency of communication between the government and the people and strengthen the relationship in co-production (Meijer, 2014; Pestoff, 2006). People with higher educational levels are more likely to participate in new forms of co-production, including network political inquiry. (2) Deviating from the educational level of the public individual, this study focuses on the level of regional education development with respect to geographical background characteristics. Regional education levels not only reflect the proportion of students in school and the quality of the education atmosphere, but also, to some extent, people’s collective initiative and enthusiasm in facing challenges. (3) Both of the aforementioned survey studies were conducted in developed countries in Europe, and Australia, which considerably differ from China in terms of their economic development stage and social and cultural background; indubitably, different countries and scenarios will provide differing results.

Studies have demonstrated that individuals with longer years of education tend to have higher levels of health (Li and Zhao, 2023), and those with higher educational levels are less likely to refuse vaccination or hesitate to do the same (Stosic et al., 2021; Schwarzinger et al., 2021). Rattay et al. (2021) through survey research, found that education is a determining factor in people’s COVID-19 risk perception and related knowledge, subsequently influencing protective behaviors such as reducing contacts, maintaining social distance, hand hygiene, and mask-wearing.

In summary, in regions with higher levels of education, the impact of science literacy on co-production in pandemic prevention and control is more significant. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate regional education level into this study and propose the second hypothesis:

H2: Regional educational levels can positively moderate the effect of public’s science literacy on co-production in the battle against pandemic.

Local government capacity

When a crisis occurs, the government’s command and mobilization, resource scheduling, service supply, and other capabilities become important. Numerous studies have regarded government capacity as an important organizational factor for successful government response to public health crises (Greer et al., 2020; Christensen et al., 2016). Enhancing the efficiency of the organization, rational delineation of responsibilities between the government and other societal entities, is one effective approach for the government to respond to public crises and a crucial manifestation of local government capacity.

From the government’s perspective, when a pandemic breaks out, relevant departments need to release pandemic information simultaneously, allocate social resources, and scientifically formulate pandemic prevention policies and effectively implement them. These require local governments to have strong technical means and governance levels. A study of five Asian countries and regions in the early stages of COVID-19 found that competent governments responded to crises faster, resources more extensively, and used more diverse policy tools (Yen et al., 2022). Further, as an important part of government capacity, government crisis communication is critical during the pandemic (Hyland-Wood et al., 2021). Rumors spread during emergencies require the government to adopt an effective communication strategy when dealing with crises (Fu et al., 2020), ensure transparent information disclosure (Huang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022), and to reduce the spread of rumors and the perceived psychological cost of public co-production. Finally, stronger government capacity denotes that governments will use more effective and advanced technologies to achieve their goals. For example, several governments are increasingly adopting novel information technologies to promote public co-production.

From the public’s perspective, the stronger the government’s capability, the higher the public’s trust, and the more willing they are to invest time, energy, and even money to participate in pandemic prevention and control. Only when the government implements relevant emergency measures and supplies, can the public be effectively mobilized to comply with the pandemic prevention policies, such as home isolation, avoidance of gatherings, and maintenance of social distancing, and jointly shoulder the social responsibility of pandemic prevention and control. Empirical evidence from China similarly demonstrated a significant correlation between the level of public’s trust in officials and their preventive behaviors against COVID-19 (Zhong et al., 2020).

Therefore, it is necessary to introduce local government capacity into this study, hence the third hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H3: Local government capacities can positively moderate the effect of the public’s science literacy on co-production in the battle against pandemic.

Methods

Model construction

Hypothesis testing was conducted by using statistical tools such as Stata 17.0 through the following methods: The ordinary least square (OLS) was employed to construct a regression model, with science literacy as the core explanatory variable and public co-production as the explained variable. Other factors that may affect public co-production were included in the model as control variables to assess the effectiveness of anti-pandemic efforts based on intellectualism. Equation (1) is expressed as follows:

where (i) represents the city, and ({Co}-{production}) represents public co-production to fight against the pandemic measured by Baidu Index, which will be explained in detail later. ({Scien}{cel}{iteracy}) represents the regional public’s science literacy level, with a focus on the magnitude and direction of coefficient ({beta }_{1}); (C{ontrol}) is a series of control variables, including urban environmental-level and individual-level variables; (varepsilon) is the random disturbance term.

Interdependence may exist between the public’s science literacy and their search behavior, which results in the endogeneity problem of the model. On one hand, faced with the threat of new viruses, those with high science literacy are more likely to frequently search for information released by official media and experts through search engines and adopt effective protective measures to avoid infection. On the other hand, through online searching for anti-pandemic information, the public can be more advisable for the sciences to combat the pandemic. Such ready-to-use scientific information for specific infectious diseases cannot immediately improve the public’s overall science literacy, but can enhance their personal trust in science and improve their scientific knowledge level. To address the endogeneity, this study utilized the ratio of research and development (R&D) personnel to the average annual population in 2017 as the instrument variable of science literacy level and adopted the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method to identify the role of the public’s science literacy in their co-production to combat the pandemic. R&D personnel are the core component of scientific and technological talents, and the ratio between R&D personnel and the population is commonly used to measure the level of regional scientific and technological development (Wang and Zhang, 2021). On the one hand, R&D personnel are significant to regional innovation development, and public science literacy tends to be higher in cities with a high proportion of R&D personnel. On the other hand, the proportion is relatively exogenous to public search behavior, and this does not directly affect public search behavior.

Second, regional education level and local government capacity were respectively introduced into the model as moderators to evaluate their moderating effects on the relationship between science literacy and public co-production to fight against the pandemic, as illustrated in Eq. (2):

where ({Modvariabl}e) is a moderate variable, focusing on the magnitude and direction of the interaction term coefficient ({beta }_{3}).

Finally, to analyze heterogeneity, Eq. (1) was used to conduct a regression test for different stages of the anti-pandemic efforts, and different regions and cities of varying sizes.

Variable description and data sources

Dependent variables: public co-production to fight against COVID-19, measured by the Baidu Index

Public co-production is crucial in major public health emergencies (Bovaird et al., 2014), and wearing masks, reducing gatherings, and vaccinating are the most direct manifestations of public co-production to fight against COVID-19, but data are difficult to collect. With the development of the Internet, information technology can significantly enhance the frequency of interaction between the government and the public, and improve public participation in public services. Extant literature demonstrates that public crisis, such as terrorist attacks and pandemics, increase the public’s search for and access to information (Althaus, 2002; Ginsberg et al., 2009). Therefore, referring to previous studies (Wu et al., 2022), we use Baidu Index as a measure of the public’s co-production to fight against COVID-19, specifically the number of searches per 10,000 people in Baidu for the seven keywords (Taking Beijing as an example, with an average annual population of 13.87 million in 2020, the sum of the total number of searches for the seven keywords mentioned above during the COVID-19 pandemic is 3,728,241, so the number of searches per 10,000 people in Beijing is 2,687.99, and its logarithmic value is about 7.89655). At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, people’s awareness of the disease was extremely poor, and the demand for the relevant information skyrocketed. Keyword searching reflect the public’s learning process as effective measure to stop the virus’ spread, which is an important embodiment of the public’s cooperation response to pandemics.

Compared with existing measurement methods, Baidu Index has the following advantages: (1) Representativeness. With 989 million Chinese netizens in 2020, accounting for 76.7% of the total population, the Internet has played an active role in the fight against COVID-19Footnote 1; the penetration rate of Baidu’s search reaches 90.9% in China, which is much higher than that of other similar search engines, and the data reflects the public’s search behavior well in ChinaFootnote 2. (2) Objectivity. Existing studies often investigate public attitudes toward public co-production through questionnaires, and the survey respondents may choose options consistent with social values under pressure, resulting in systematic bias. Baidu index is based on netizen search records, which represents itself as an objective tool. (3) Voluntariness. Baidu Index reflects the active search behavior of netizens, echoing the definition in Brandsen and Honingh (2016) about co-production of the public’s “voluntary” and “non-compulsory”. (4) Accessibility. Data are easily and quickly accessible.

Independent variables: public’s science literacy

With cities as the study sample, the percentage of citizens with science literacy in a city is taken as the level of citizens’ science literacy in that city, and the data is derived from the 2020 Chinese Citizens’ Scientific Quality Sampling Survey conducted by China Association for Science and Technology in 2020, whose measurement items include three core dimensions: mastery of the scientific knowledge, utilization of the scientific method and scientific ability, and the effect of understanding science on individuals and society. Those whose questionnaire scored more than 70 points were judged to be science literacy, and the level of the public’s science literacy in a city was weighed by the distribution and structure of the city’s population (He et al., 2021).

Moderating variable: regional educational levels and local government capacity

Referring to previous studies (Ji et al., 2018), the number of urban middle school students to the total population is used as an indicator of regional education level. The provincial number of defaulters in cities has been used to measure government capacity and to study its relationship between government information disclosure and the public’s co-production (Wu et al., 2022). We also measure the local government’s capacity using the number of discredited people at the provincial level in cities, with data derived from the China Enforcement Information Disclosure Network (CEDIN, http://zxgk.court.gov.cn/). Established by China Supreme People’s Court in 2013, the website publishes a list of discredited people who have refused to carry out their judgments and the specific duration of their defaulter status. The number of discredited people at the provincial level has been used as a proxy variable for the government’s enforcement capacity to measure its legal capacity (Besley and Persson, 2009).

Control variables

The study controlled for other variables that could affect co-production. In terms of environmental factors, political, economic, and social conditions shape the nature of community problems and public perceptions of them, which in turn affects the public’s willingness to participate in public services (Percy, 1984; Alford, 2002). The size of the nonprofit sector also has a significant impact on co-production (Paarlberg and Gen, 2009). In addition, since the explanatory variables are measured by Baidu Index, the level of network development and the status of government services also affect the public’s search status. Individual factors, public participation ability, economic status, sense of community belonging and attitude toward government and society also affect public co-production (Van Ryzin et al., 2017). In summary, in this paper, GRP, income, science and technology level, number of foundations, government network transparency, level of digital government development, and the objective level, including public government trust, social trust, and social justice are selected as control variables.

The data required for this paper mainly come from the 2020 National Survey of Civic Scientific Literacy in China, the official website of Baidu Index, and China Urban Statistical, etc., and 140 cities were finally obtained as the study sample.

Variables descriptions and descriptive statistics are illustrated in Table 1.

Sample selection and data collection

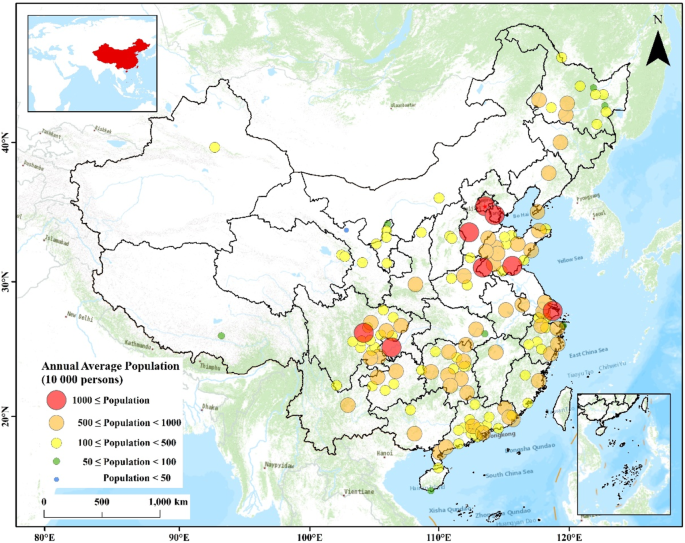

Based on the open data from the 2020 National Survey of Civic Scientific Literacy in China, this study sampled 140 cities. In terms of population size, the sample population is 703.76 million, about half of China’s total population; in terms of structure, the cities include four municipalities, namely Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai and Chongqing, all directly under the central government, all provincial capitals, and some prefectural level cities, which are distributed in the eastern, central, and western regions of China (which account for 42.86%, 25.71%, and 31.43% respectively). Based on the stages in the White Paper Fighting COVID-19 China in ActionFootnote 3, search data of seven keywords from Baidu Index that covered four stages of the fight against COVID-19 were collected from December 27, 2019 to April 28, 2020; this could better reflect the entire process of Chinese public fight against the pandemic. It should be noted that although the 2020 National Survey of Civic Scientific Literacy obtained for the first time the status of civic science literacy in China’s 341 prefectual level cities and above, the relevant data were not all publicized, and our study has collected data from all the cities that have been made public as far as possible. The sample distribution is shown in Fig. 1.

The illustration is created by the author. The color and radius of the circles are based on the city size.

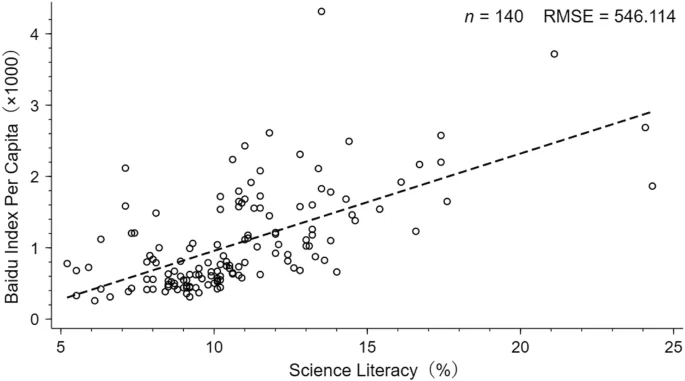

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the linear fitting diagram of the public’s science literacy and co-production against the pandemic is demonstrated. With the continuous improvement of cities’ science literacy level, the per 10,000 capita Baidu search volume has gradually increased, indicating the more co-production in the battle against a pandemic, which agrees with hypothesis H1. Still, the role of the public’s science literacy in their co-production to combat the pandemic should be further tested.

Data from the 2020 National Survey of Civic Scientific Literacy in China, Official Website of Baidu Index.

Results

Baseline regression

Table 2 reports the baseline regression results of the influence of the public’s science literacy level on co-production in the fight against COVID-19. With the test logic of econometrics starting from the general to the specific cases, a series of control variables were gradually included in the regression model.

Model (1) only included the core explanatory variables without the addition of any control variables, and the science literacy was significantly positive at 1%. In model (2), six control variables at the objective level of the city were added based on (1), and the science literacy was still significantly positive at 1%. On the basis of (2), model (3) further included three subjective control variables—such as the public’s government trust in the model—and the science literacy was still significantly positive at 1%, consistent with the results of the previous two regression steps. The determination coefficient increased from 0.38 to 0.59, and the fitting degree was thus improved. This indicated that the higher the level of the city’s science literacy, the more the co-production against the pandemic. The coefficient of science literacy gradually increased from 0.117 to 0.142, indicating that science literacy’s influence was increasingly apparent. Model (3) demonstrates that every 1% increase in the public’s science literacy can increase the per capita search volume of COVID-19-related keywords by the public by 14.2%, that is, public co-production against the pandemic increased by 14.2%, which verifies H1.

Endogeneity test

To further address the potential endogeneity problem in the model, a 2SLS model was used to accurately estimate the impact of public science literacy on the public co-production, with the ratio of urban R&D personnel to the annual average population in 2017 as the instrumental variable.

As demonstrated in Table 3, (1) and (2) reported the results of the two-stage regression with the instrumental variable. The regression results of the first stage (1) indicated that the regression coefficient of the proportion of R&D personnel in the city was significantly positive at the 1% level, which denoted that the higher the ratio of urban R&D personnel in the city, the higher the public’s science literacy in the city. The correlation hypothesis of the instrumental variable is valid. Meanwhile, the partial R2 is 0.32, and the F-statistic of the significance test is 32.68. The instrumental variable has strong explanatory power. The results of the second stage (2) regression demonstrated that after addressing the endogeneity problem, the positive influence of the public’s science literacy on co-production was still significantly positive at 1%. Specifically, with the increase of science literacy by 1%, public co-production increased by 42.5%, which was about three times that of the baseline regression result, which indicated that the promoting effect of the public’s science literacy on co-production during COVID-19 may be underestimated due to the endogeneity problem. It was verified that science literacy contributes to promoting co-production against the pandemic. Thus, H1 is supported.

Moderating effect of educational level and government capacity

To test the moderating effect of regional educational levels, the proportion of urban secondary school students (Edu_c) was used to measure educational level. The intersection term of regional education level and science literacy was added into the regression model, along with a series of control variables. As illustrated in Table 4, no control variables were added to model (1); only objective control variables were added to model (2), and subjective control variables were further added to model (3). The results demonstrated that the coefficient of the intersection term gradually increased from 0.471 to 1.049, and the significance level gradually rose. The intersection term of model (3) was significantly positive at the 5% level, and the determination coefficient was 0.69, which was better than that of model (3). The coefficient of the interaction term gradually increased from 0.038 to 0.046, and the significance level gradually increased; the determination coefficient increased from 0.51 to 0.62, and the degree of fitting was improved. Model (3) illustrated that the intersection term was significantly positive at the 5% level.

Similar to the approach for testing the moderating effect of regional education level, the number of discredited people (Capacity_c) of the city was used to measure the local government capacity. The greater the number, the worse the local government capacity. As demonstrated in models (4), (5), and (6), the coefficient of the interaction term gradually decreased from −0.009 to −0.020, and the significance level gradually became higher. The interaction term of the model (6) was significantly negative at 1% level.

Figure 3 shows the separate plotting of the moderating effects of regional education level and local government capacity on the public’s scientific literacy and co-production in the fight against COVID-19. In the left graph, when Edu_c is greater than 0, the marginal effect is significantly positive within the 95% confidence interval. This means that the marginal effect of the public’s science literacy on co-production of fight against COVID-19 gradually increases with the increase of the proportion of the number of students in the city. In the figure on the right, when Capacity_c is <11.77 (The natural logarithmic value of 129,000 is about 11.7, so the number of discredited people at the provincial level in the city is 129,000), the marginal effect is significantly negative within the 95% confidence interval. This means that when the number of provincial-level discredited people in the city is less than 129,000, the marginal effect of the public’s science literacy on co-production in the fight against the pandemic gradually increases as the number of discredited people decreases.

Controls were applied for GRP, income level, science and technology level, number of foundations, government network transparency, digital government development level, public’s government trust, social trust, and social justice. The dashed line was at a marginal effect of zero. Full regression estimates are provided in Table 4 models with 95% confidence interval.

Both the regression results and the moderating effect graphs indicate that the level of urban education and the local government capacity have a positive impact on the effectiveness of the public’s science literacy in promoting co-production fight against COVID-19, supporting hypothesis H2 and H3.

Robustness of test results

Whether the baseline regression results are affected by sample selection needs to be further tested. As demonstrated in Table 5, owing to a small number of outliers in the explained variables, the explained variables in models (1) and (2) were, respectively, treated with bilateral tail reduction and bilateral censoring at the 5% quantile to avoid the deviation of coefficient estimation, and all control variables were added to perform regression estimation. Additionally, this study further replaced the data and the public’s science literacy at the city level with those at the provincial level and added all control variables, as demonstrated in the model (3). Clearly, the coefficients of science literacy are all significantly positive at 1% level, and the baseline regression results are still robust.

Heterogeneity analysis

The results of the baseline regression are the embodiment of the total effect, and the unique properties of different stages and regions may affect the manifestation of science literacy. This section analyzes the heterogeneity of the stage of the pandemic, geographical location, and city size in terms of the two dimensions of time and space.

With the continuous development of the pandemic situation, the external conditions and the public’s willingness in co-production may change. To further explore the dynamic changes of the public’s anti-pandemic efforts, this section studies separate regression testing across all stages – including Stage I: Swift Response to the Public Health Emergency (27 December 2019–19 January 2020), Stage II: Initial Progress in Containing the Virus (20 January–20 February 2020), Stage III: Newly Confirmed Domestic Cases on the Chinese Mainland Drop to Single Digits (21 February–17 March 2020), and Stage IV: Wuhan and Hubei-An Initial Victory in a Critical Battle (18 March–28 April 2020); various models that joined all control variables.

As demonstrated in Table 6, the science literacy coefficients of stages I, II, III, and IV were 0.160, 0.132, 0.152, and 0.160, respectively; they were all significantly positive at 1% level, which indicated that the public’s science literacy to the pandemic was effective in all stages. The science literacy coefficient first decreased and then increased. The science literacy coefficient was the same in stages I and IV, and the promoting effect of science literacy on the co-production was relatively obvious, which indicated that the promoting effect of the public’s science literacy in different stages was different. In general, the promoting effect of science literacy was statistically significant in the whole process of the fight against the pandemic in each stage, which further verified the correctness of H1.

China is a country with vast territory, and heterogeneity in different regions will affect the public’s willingness and cost of co-production in response to the pandemic. The sample cities, based on different characteristics in different geographical locations, were classified into three subregions: eastern, central, and western regions. Specifically, the eastern region includes cities in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan; the central region includes cities in Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, and Anhui; the western region includes cities in Inner Mongolia, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang. Thereafter, subsample regression was performed. All control variables were added to each model.

As demonstrated in Table 7, models (1), (2), and (3) reflect the differences in the public’s anti-pandemic effort based on scientific knowledge in the cities across regions. The science literacy coefficients of cities in eastern, central, and western regions were 0.141, 0.250, and 0.193, respectively, and all of them were significantly positive at 1%, which further supported H1. The estimated coefficient of 0.141 in the eastern region was smaller than that in the central and western regions. It is reasonable to suspect that the promoting effect of the public’s science literacy is smaller in the eastern region and relatively larger in the central and western regions.

To answer the aforementioned questions, we further explore the differences between regions. By adding the intersection terms of regional dummy variables and science literacy (E_M×S_L, E_W×S_L, and E_MW×S_L), the difference test of regression coefficient between eastern and central, eastern and western, and eastern and central and western regions, was conducted. The results demonstrated that the coefficients of the interaction terms were all significantly positive, which indicated that a statistically significant difference existed in the coefficient of science literacy between the eastern region and other regions, and the science literacy in the central and western regions played a more evident role in the promotion of the public co-production against the pandemic.

The size of a city affects the difficulty of urban governance and challenges the level of governmental governance. Unlike small and medium-sized cities, large cities are more difficult to govern due to their large population, complicated public affairs, and diverse service demands, and various problems will become more prominent. On the contrary, larger cities have stronger incentives to innovate management models with refined management, improved institutional norms, diversified technical means, and higher enthusiasm of the public to participate in urban governance (Zou and Zhao, 2022). Therefore, the scale of the city may also affect the effectiveness of the role of the public’s science literacy in co-production, and still the role of science literacy in the promotion of co-production in those cities is not known. In China, the urban hierarchy is relatively complex, mainly consisting of municipalities directly under the central government, provincial capital cities, sub-provincial cities, prefectural level cities and county-level cities. In comparison to most prefectural level cities, municipalities directly under the central government, provincial capital cities, and sub-provincial cities possess unique advantages in terms of economy, politics, culture, and population. In this paper, they are referred to as large cities, including Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Dalian, Qingdao, Ningbo, Xiamen, Shenzhen, Shijiazhuang, Shenyang, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Fuzhou, Jinan, Guangzhou, Haikou, Taiyuan, Changchun, Harbin, Zhengzhou, Wuhan, Changsha, Hefei, Nanchang, Hohhot, Chengdu, Nanning, Guizhou, Kunming, Xi’an, Lanzhou, Xining, Yinchuan, Urumqi, Lhasa, a total of 36 cities, and all the rest cities are considered non-large cities. Therefore, this paper divided the sample into two subsamples according to aforementioned categorization; large city, and non-large city; and conducted the subsample regression, after adding all the control variables.

As demonstrated in Table 8, models (1) and (2) reflect the differences in the public’s co-production based on science literacy in cities of different scales. The science literacy coefficient of large cities was 0.082, and the significance level was 5%. The science literacy coefficient of non-large cities was 0.260, with a significance level of 1%, which also supported H1. The estimated coefficient of 0.082 for large cities was about one-third of that for non-large cities.

To further verify the statistical significance of the difference in the promotion effect of science literacy, the intersection term (L_City×S_L) was added to the model to test the difference. The results demonstrated that the coefficient of the interaction term was significantly positive, indicating that the promoting effect of science literacy on co-production against COVID-19 was stronger in non-large cities but weaker in large cities.

The above results provide us with many interesting findings. The public’s science literacy plays an important role in promoting co-production in the fight against pandemic, and there are significant differences in the performance of the effect of this role in different temporal and spatial dimensions. We also found that regional education level and local government capacity can positively moderate the relationship between the two, verifying the previous hypotheses H1, H2, and H3.

Discussion

The greatest lesson that the COVID-19 pandemic has taught mankind is to strengthen the focus on science (Von Hagke et al., 2022), which has played a key role in decision-making for the prevention and control of the pandemic, both for government departments and the public. Looking at the world as a whole, governments that performed well in pandemic control followed the principles of scientific prevention and control, rather than spreading conspiracy theories and politicizing the issue (Chan et al., 2021; Sanchez and Dunning, 2021). For the mass public, the various effective co-production measures against the pandemic are precisely sensible choices based on scientific knowledge. Merkley & Loewen’s study argues that anti-intellectualism is of central importance in shaping the public’s perception of the COVID-19 pandemic across a range of indicators (Merkley and Loewen, 2021), including risk perceptions, preventive behaviors such as social distance keeping and mask wearing, misperceptions, and information-seeking. Anti-intellectualism poses a fundamental challenge to maintaining and increasing public adherence to expert-guided COVID-19 health instructions. Similarly, Brzezinski et al. demonstrated that the proportion of people who stayed at home after shelter-in-place policies went into effect in March and April 2020 in the United States was significantly lower in counties with a high concentration of science skeptics (Brzezinski et al., 2021). However, there is a lack of existing literature examining the impact of science literacy on the co-production to fight against COVID-19 from the positive perspective of trust in science. This study, based on empirical data, confirms the positive correlation between the mass public’ science literacy and co-production in pandemic prevention and control, making up for the shortcomings of previous studies and providing new support for the scientific response to the pandemic and further evidencing the predecessors’ research finding (Bicchieri et al., 2021; Sailer et al., 2022).

Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have been the key weapon against the COVID-19 and affected virtually any societal process (Perra, 2021).Compared with the mandatory compliance driven by authoritarianism, co-production guided by the public’s science literacy is voluntary compliance, rather than being driven by power, and is a rational action based on scientific knowledge and spirit (Sailer et al., 2022), possessing sustainability and stability, which is crucial for maintaining social stability during the pandemic. However, the role of the public’s science literacy during the COVID-19 pandemic has yet to be fully tapped and utilized. Even though we call for scientific communication as an important tool for prevention and try to increase the public’s knowledge of COVID-19 and establish the idea of putting science first through popular science education (Matta, 2020), there is still a need to further strengthen the emphasis on the public’s intellectual power.

This study also found that the level of regional education and the capacity of local government during the pandemic control period positively moderated the promotion of co-production by the public’s science literacy. Regarding the role of the city’s education level: generally speaking, the city’s education level reflects the overall literacy of the public. First, pandemic prevention and control policies are not static, and government departments will dynamically adjust measures based on the pandemic situation. The higher the education level the public possess, the higher science literacy the mass public have, the easier they understand the logic of changes in government pandemic prevention policies and alleviate their own emotional resistance, demonstrating higher obedience, stronger participation, and better cooperation, thereby positively influencing co-production. In addition, residents with higher education level are more capable of using online medical platforms to obtain medical services, thereby reducing the pressure on the medical resources due to pandemic (Jiang et al., 2021). Finally, crisis communication is an important means of resolving crises, which can improve the quality and effectiveness of government-public co-production, and efficient communication also depends on the public with a certain level of education.

And regarding the role of local government capacity: the government capacity will affect the speed of response when a crises comes, as well as the flexibility of resource allocation and the diversity of policy tools during the crisis response process (Yen et al., 2022). In China, there are also differences in government capacity among different cities depending on the resource endowment, political environment, economic level and other factors. Generally speaking, the more integrated a city is, the better its government will perform in controlling the chain of transmission of the virus, the screening of close contacts, and the dissemination of pandemic information (Mao, 2021). These cities are more flexible and effective in resource allocation and technology application, achieving a dynamic balance between pandemic prevention and control and economic development. The public often subjectively evaluates government behavior based on changes in the pandemic situation and online public opinion information, and they give more positive evaluations to governments with better performance, which promotes the positive development of online public opinion and encourages the public to engage in co-production with the government during COVID-19, thereby promoting better pandemic prevention and control performance and creating a virtuous cycle.

Therefore, a regional scientific education level and government capacity are important factors influencing public co-production and are core elements in improving the overall effectiveness of crisis response and unleashing the enormous potential of public participation.

Conclusions

This study examines the correlation between the mass public’s science literacy and co-production in the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary research conclusions are as follows: firstly, science literacy could significantly promote the public’s co-production in preventing and controlling COVID-19. For every 1% increase in the number of people with science literacy in a city, the co-production increased by 14.2%. Specifically, a higher level of science literacy in a city showed increased per capita internet search volume, including “virus”, “novel corona virus”, “infectious disease” and other keywords during COVID-19, and they were more likely to comply with the government’s pandemic prevention policies, respond to the government’s social mobilization, and even participate in specific voluntary services. Secondly, the city’s education level and local government capacity positively moderate the promoting effect of the mass public’s science literacy and co-production. The higher the education level of the region, the more significant the influence of science literacy on co-production against pandemic. In a city, when the percentage of students was above 0 or the number of discredited people decreases was less than 129,000, as the percentage increases or the number of trust-breaking people decreases, the marginal effect of the public’s science literacy on co-production gradually increased with the increase in the number of colleges. And finally, the performance of the mass public’s science literacy on co-production demonstrated a certain heterogeneity in different stages of pandemic prevention, different regions, and cities of varying scales. Regarding the time dimension, science literacy at the beginning (Stage I) and end (Stage IV) played a more significant role in promoting pandemic co-production, which indicated a downward trend at first, followed by an upward trend. In terms of the spatial dimension, in the central and western regions and non-large cities of China, the public’s science literacy played a strong role in the promotion of co-production, which demonstrated that with the continuous improvement of regional economic development and industrialization, the effect of the public’s science literacy on the promotion of pandemic co-production decreased.

This paper’s possible marginal contributions are (1) based on city-level data in China, the study verified the relationship between science literacy and co-production of pandemic prevention and control, which provides a new research perspective for understanding the role of science literacy in public health crisis. (2) The study fully takes into account the moderating effect of factors such as regional education level and local government capacity on the impact of science literacy, as well as the heterogeneity of science literacy in different stages, different regions, and cities of different scales, which contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between science literacy and the effectiveness in the battle against pandemic.

It should be noted that although this paper analyzes the impact of the public’s science literacy on co-production in the fight against COVID-19, we believe that human behavior is complex and that the science literacy level cannot fully explain all behaviors of the public in compliance with pandemic prevention and control policies. Rather, it is only an important underlying factor that influences public co-production during an emergent public health crisis. And this study uses cross-sectional data to test the effectiveness of the role of science literacy, which is feasible but still needs further exploration. In the future, multi-modal data and more innovative methods are expected to better reveal the interaction between the mass public’s science literacy and co-production in public affairs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

-

The population data are from China Internet Network Information Center, The 47th China Statistical Report on Internet Development, http://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/old_attach/P020210203334633480104.pdf.

-

The data of China netizen search engine usage are from China Internet Network Information Center, 2019 China Netizen Search Engine Usage Report, http://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/old_attach/P020191025506904765613.pdf.

-

The stage definition of the pandemic are from The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Fighting COVID-19: China in Action, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-06/07/content_5517737.htm.

References

-

Alford J (2002) Defining the client in the public sector: a social-exchange perspective. Public Adm Rev 62(3):337–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00183

Google Scholar

-

Alford J, Yates S (2016) Co-production of public services in Australia: the roles of government organisations and co-producers. Aust J Public Adm 75(2):159–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12157

Google Scholar

-

Alonso JM, Andrews R, Clifton J, Diaz-Fuentes D (2019) Factors influencing citizens’ co-production of environmental outcomes: a multi-level analysis. Public Manag Rev 21(11):1620–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1619806

Google Scholar

-

Althaus SL (2002) American news consumption during times of national crisis. Political Sci Politics 35(3):517–521

Google Scholar

-

Besley T, Persson T (2009) The origins of state capacity: property rights, taxation, and politics. Am Econ Rev 99(4):1218–1244. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.4.1218

Google Scholar

-

Bicchieri C, Fatas E, Aldama A, Casas A, Deshpande I, Lauro M, Parilli C, Spohn M, Pereira P, Wen RL (2021) In science we (should) trust: expectations and compliance across nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 16 (6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252892

-

Bonsón E, Perea D, Bednárová M (2019) Twitter as a tool for citizen engagement: an empirical study of the Andalusian municipalities. Gov Inf Q 36(3):480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.03.001

Google Scholar

-

Bovaird T, Briggs I, Willis M (2014) Strategic commissioning in the UK: service improvement cycle or just going round in circles? Local Gov Stud 40(4):533–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.805689

Google Scholar

-

Brandsen T, Honingh M (2016) Distinguishing different types of coproduction: a conceptual analysis based on the classical definitions. Public Adm Rev 76(3):427–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12465

Google Scholar

-

Brudney JL, England RE (1983) Toward a definition of the coproduction concept. Public Adm Rev 43:59-65

-

Brzezinski A, Kecht V, Van Dijcke D, Wright A (2020) Belief in science influences physical distancing in response to COVID‐19 lockdown policies. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper 2020‐56

-

Brzezinski A, Kecht V, Van Dijcke D, Wright AL (2021) Science skepticism reduced compliance with COVID-19 shelter-in-place policies in the United States. Nat Hum Behav 5(11):1519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01227-0

Google Scholar

-

Chan HW, Chiu CPY, Zuo SJ, Wang X, Liu L, Hong YY (2021) Not-so-straightforward links between believing in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and engaging in disease-preventive behaviours. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00781-2

-

Chatfield AT, Reddick CG (2018) All hands on deck to tweet #sandy: Networked governance of citizen coproduction in turbulent times. Gov Inf Q 35(2):259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.09.004

Google Scholar

-

Christensen T, Laegreid P, Rykkja LH (2016) Organizing for crisis management: building governance capacity and legitimacy. Public Adm Rev 76(6):887–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12558

Google Scholar

-

Egerton M (2002) Higher education and civic engagement. Brit J Soc 53(4):603–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007131022000021506

Google Scholar

-

Fu Y, Ma WH, Wu JJ (2020) Fostering voluntary compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic: an analytical framework of information disclosure. Am Rev Public Adm 50(6-7):685–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942102

Google Scholar

-

Ginsberg J, Mohebbi MH, Patel RS, Brammer L, Smolinski MS, Brilliant L (2009) Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 457(7232):1012–U1014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07634

Google Scholar

-

Greer SL, King EJ, da Fonseca EM, Peralta-Santos A (2020) The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Glob Public Health 15(9):1413–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

Google Scholar

-

Guterres. A (2020) Shared responsibility, global solidarity: responding to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/shared-responsibility-global-solidarity-responding-socio-economic-impacts-covid-19. Accessed 12 Sept 2022

-

He L, He CY, Reynolds TL, Bai QS, Huang YC, Li C, Zheng K, Chen YA (2021) Why do people oppose mask wearing? A comprehensive analysis of US tweets during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Inf Assn 28(7):1564–1573. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab047

Google Scholar

-

He W, Zhang C, Ren L, Huang YL (2021) Chinese civic scientific literacy and their attitudes toward science and technology—main findings from the 2020 national survey of civic scientific literacy in China. Stud Sci Popularization 16(02):5–17+107. https://doi.org/10.19293/j.cnki.1673-8357.2021.02.001. in Chinese

Google Scholar

-

Huang L, Li OZ, Wang BQ, Zhang ZL (2022) Individualism and the fight against COVID-19. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01124-5

-

Huang L, Li OZ, Yi Y (2021) Government disclosure in influencing people’s behaviors during a public health emergency. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00986-5

-

Hyland-Wood B, Gardner J, Leask J, Ecker UKH (2021) Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00701-w

Google Scholar

-

Ji XL, Wei J, Li XZ (2018) Setting counties to districts vs. district expansion: empirical study on the effect of expanding municipal districts of prefectural-level city to economic development. Social Sciences in Guangdong (06):46-57. (in Chinese)

-

Jiang XH, Xie H, Tang R, Du YM, Li T, Gao JS, Xu XP, Jiang SQ, Zhao TT, Zhao W, Sun XZ, Hu G, Wu DJ, Xie GT (2021) Characteristics of online health care services from China’s largest online medical platform: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res 23(4):14. https://doi.org/10.2196/25817

Google Scholar

-

Kahan DM, Jenkins-Smith H, Braman D (2011) Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J Risk Res 14(2):147–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

Google Scholar

-

Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, Karukivi M, Lindfelt M, Antfolk J (2021) Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Differ 172:11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590

Google Scholar

-

Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K (2016) Motivated rejection of science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 25(4):217–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416654436

Google Scholar

-

Li HF (2020) Communication for coproduction: increasing information credibility to fight the coronavirus. Am Rev Public Adm 50(6-7):692–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942104

Google Scholar

-

Li Z, Zhao MH (2023) Effects of education level on health and its underlying mechanism: an empirical analysis based on China Family Panel Studies. Chin J Health Policy 16(01):42–51. in Chinese

-

Mann M (1984) The autonomous power of the state: its origins, mechanisms and results. Eur J Sociol/Arch Eur éennes de Sociol 25(2):185–213

Google Scholar

-

Mao YX (2021) Political institutions, state capacity, and crisis management: a comparison of China and South Korea. Int Political Sci Rev 42(3):316–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512121994026

Google Scholar

-

Matta G (2020) Science communication as a preventative tool in the COVID19 pandemic. Hum Soc Sci Commun 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00645-1

-

McNeill WH (1976) Plagues and Peoples. Anchor

-

McPhetres J, Rutjens BT, Weinstein N, Brisson JA (2019) Modifying attitudes about modified foods: Increased knowledge leads to more positive attitudes. J Environ Psychol 64:21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.04.012

Google Scholar

-

Meijer AJ (2014) New media and the coproduction of safety: an empirical analysis of dutch practices. Am Rev Public Adm 44(1):17–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074012455843

Google Scholar

-

Merkley E, Loewen PJ (2021) Anti-intellectualism and the mass public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 5(6):706-+. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01112-w

Google Scholar

-

Motoki K, Saito T, Takano Y (2021) Scientific literacy linked to attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccinations: a pre-registered study. Front Commun 6:707391. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.707391

Google Scholar

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016) Science literacy: concepts, contexts, and consequences. National Academies Press (US)

-

Paarlberg LE, Gen S (2009) Exploring the determinants of nonprofit coproduction of public service delivery the case of k-12 public education. Am Rev Public Adm 39(4):391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008320711

Google Scholar

-

Parrado S, Van Ryzin GG, Bovaird T, Loffler E (2013) Correlates of co-production: evidence from a five-nation survey of citizens. Int Public Manag J 16(1):85–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2013.796260

Google Scholar

-

Percy SL (1984) Citizen participation in the coproduction of urban services. Urban Aff Q 19(4):431–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208168401900403

Google Scholar

-

Perra N (2021) Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Phys Rep. -Rev Sec Phys Lett 913:1–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2021.02.001

Google Scholar

-

Pestoff V (2006) Citizens and co-production of welfare services – childcare in eight European countries. Public Manag Rev 8(4):503–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030601022882

Google Scholar

-

Rattay P, Michalski N, Domanska OM, Kaltwasser A, De Bock F, Wieler LH, Jordan S(2021) Differences in risk perception, knowledge and protective behaviour regarding COVID-19 by education level among women and men in Germany. Results from the COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO) study. PLoS ONE 16(5):e0251694. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251694

Google Scholar

-

Rutjens BT, Sutton RM, van der Lee R (2018) Not all skepticism is equal: exploring the ideological antecedents of science acceptance and rejection. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 44(3):384–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217741314

Google Scholar

-

Sailer M, Stadler M, Botes E, Fischer F, Greiff S (2022) Science knowledge and trust in medicine affect individuals’ behavior in pandemic crises. Eur J Psychol Educ 37(1):279–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00529-1

Google Scholar

-

Sanchez C, Dunning D (2021) The anti-scientists bias: the role of feelings about scientists in COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors. J Appl Soc Psychol 51(4):461–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12748

Google Scholar

-

Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S (2021) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health 6(4):E210–E221. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(21)00012-8

Google Scholar

-

Shao CY, Li SJ, Zhu F, Zhao DH, Shao H, Chen HX, Zhang ZR (2020) Taizhou’s COVID-19 prevention and control experience with telemedicine features. Front Med 14(4):506–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-020-0811-8

Google Scholar

-

Sigerist. HE (2018) Civilization and Disease. Cornell University Press

-

Stosic MD, Helwig S, Ruben MA (2021) Greater belief in science predicts mask-wearing behavior during COVID-19. Pers Individ Differ 176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110769

-

Sturgis P, Brunton-Smith I, Jackson J (2021) Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nat Hum Behav 5(11):1528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01115-7

Google Scholar

-

Su CH (2020) The results of the anti-epidemic strategy have fully demonstrated China’s strength. http://paper.ce.cn/pc/content/202009/30/content_241606.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2024

-

Sundeen RA (1988) Explaining participation in coproduction: a study of volunteers. Soc Sci Q 69(3):547

-

Thomsen MK (2017) Citizen coproduction: the influence of self-efficacy perception and knowledge of how to coproduce. Am Rev Public Adm 47(3):340–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074015611744

Google Scholar

-

Valladares L (2021) Scientific literacy and social transformation critical perspectives about science participation and emancipation. Sci Educ 30(3):557–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00205-2

Google Scholar

-

Van Ryzin GG, Riccucci NM, Li HF (2017) Representative bureaucracy and its symbolic effect on citizens: a conceptual replication. Public Manag Rev 19(9):1365–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1195009

Google Scholar

-

Von Hagke C, Hill C, Hof A, Rinder T, Lang A, Habel JC (2022) Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic crisis to overcome the global environmental crisis. Sustainability 14(17):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710545

Google Scholar

-

Voorberg WH, Bekkers V, Tummers LG (2015) A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag Rev 17(9):1333–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

Google Scholar

-

Wang JY, Zhang H (2021) Can international tourism trade alleviate regional income gap? Bus Manag J 43(5):75–92. https://doi.org/10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2021.05.005. in Chinese

Google Scholar

-

Wang P, Liang XF (2020) The role of professional associations in dealing with public health emergencies: taking responses to novel coronavirus pneumonia as an example. Adm Reform 03:17–22. https://doi.org/10.14150/j.cnki.1674-7453.20200307.003. in Chinese

Google Scholar

-

Wu YP, Xiao HY, Yang F (2022) Government information disclosure and citizen coproduction during COVID-19 in China. Gov -Int J Policy Adm Inst 35(4):1005–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12645

Google Scholar

-

Yen WT, Liu LY, Won E, Testriono (2022) The imperative of state capacity in public health crisis: Asia’s early COVID-19 policy responses. Gov -Int J Policy Adm Inst 35(3):777–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12695

Google Scholar

-

Zhao T, Wu ZS (2020) Citizen-state collaboration in combating COVID-19 in China: experiences and lessons from the perspective of co-production. Am Rev Public Adm 50(6-7):777–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942455

Google Scholar

-

Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, Li Y (2020) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci 16(10):1745–1752. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45221

Google Scholar

-

Zou YH, Zhao WX (2022) Neighbourhood governance during the COVID-19 lockdown in Hangzhou: Coproduction based on digital technologies. Public Manag Rev 24(12):1914–1932. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1945666

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This research is jointly funded by the Key Project of Social Science of MOE (grant 22JZD028), Key project of National Social Science Foundation (grant 22AMZ003), Key Project of Xinjiang Social Science Foundation (grant 20AZD006), 2024 Xinjiang Basic Research Operating Expenses for Scientific Research Project (grant XJEDU2024J012), and Postgraduate Research and Innovation Project of Xinjiang (grant XJ2022G074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haibo Qin: conceptualization, methodology, study design, writing-original draft, writing-review, supervision, and funding acquisition. Zhongxuan Xie: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, data analysis, study design, writing-original draft, and editing. Huping Shang: methodology, writing-review, and funding acquisition. Yong Sun: methodology, writing-review, and editing. Xiaohui Yang: data collection, data curation, and data analysis. Mengming Li: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, study design, writing-review, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

code.docx

City Classification in Fig1.xls

all data.xlsx

Baidu search index by keywords.xlsx

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, H., Xie, Z., Shang, H. et al. The mass public’s science literacy and co-production during the COVID-19 pandemic: empirical evidence from 140 cities in China.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 834 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03304-x

-

Received: 06 August 2023

-

Accepted: 10 June 2024

-

Published: 26 June 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03304-x