Almost four years ago, the novelist Adam Biles was talking to a friend about the fact that the work of George Orwell was due to enter the public domain on New Year’s Day 2021. Under UK law, copyright expires 70 years after the end of the calendar year of the author’s death; Orwell died in 1950. The two men joked about possible sequels: the aftermath of Nineteen Eighty-Four could be explored in Nineteen Eighty-Five, or Keep the Aspidistra Flying could spawn Keep the Aspidistra Still Flying. Perhaps there could even be a sequel to Animal Farm? “I didn’t actively think any more of it for a few months but it kept coming back to me,” Biles tells BBC Culture. “It was one of those frivolous ideas that stuck.”

More like this:

– Why Orwell’s 1984 could be about now

– The world’s most misunderstood novel

– 25 of the best books of the year so far

On furlough from his job as literary director at the celebrated Paris bookshop Shakespeare and Company during the Covid-19 lockdown, Biles began writing what would become Beasts of England. “I went into it as a literary experiment,” he says. “I always hoped that I would finish it and send it to people but I never felt any guarantee. I didn’t know for sure that any publisher would want to touch it.” He was well aware that he was playing with one of the most beloved books in the English language. “When I mentioned it to people, they would say, ‘Ooh, that’s bold,’ which I took as meaning, ‘Oh, you’re going to get a lot of shit for this.’ Orwell is one of those writers who people feel proprietorial towards.”

Around the same time, Bill Hamilton of the literary agency AM Heath was also thinking about life after copyright. The agency has represented Orwell’s estate since 1950, and Hamilton has been personally responsible for it since 1989. He wanted to get on the front foot by commissioning somebody to reimagine Nineteen Eighty-Four from the perspective of Julia, Winston Smith’s lover and fellow dissident. “I’ve always thought that Animal Farm is not just unimprovable, it’s inimitable,” Hamilton tells BBC Culture. “Nineteen Eighty-Four’s very different. It’s full of narrative holes which beg to be filled: who on earth was Julia? Where did she come from? Was she spying on him? What if Julia was relating this story? It begged to be written and you needed somebody with great sophistication to embark on it.” He chose Sandra Newman, the US author whose work includes the dystopian novels The Men and The Country of the Ice Cream Star. After re-reading Nineteen Eighty-Four and seeing the narrative potential, Newman leapt at the opportunity. “Orwell left a lot of money on the table for me,” she tells BBC Culture. “I tried to spend it wisely.”

Every literary estate is trepidatious about the expiry of copyright, for both financial and creative reasons. Until her death in 1980, the zealous gatekeeper of Orwell’s legacy was his widow Sonia, who thwarted numerous would-be biographers. Most famously, she denied David Bowie permission to write a rock musical of Nineteen Eighty-Four, a project that mutated into his 1974 album Diamond Dogs. Hamilton has been much more generous to biographers and scholars but has kept a close eye on what we would now call the IP. “They were quite heavy on people who came up with things like Animal Farm: The Musical,” says DJ Taylor, author of Orwell: The New Life. “Everything was tightly monitored in terms of preserving the integrity of ‘the brand’, to use that terrible phrase.”

In 1983, the Hungarian writer György Dalos published an unlicensed sequel, 1985, but copyright enforcement behind the Iron Curtain was not a top priority. In the UK, Orwell-curious novelists used to have to turn to the writer’s life rather than his copyrighted words, producing semi-biographical novels such as Norman Bissell’s Barnhill, David Caute’s Dr Orwell and Mr Blair, and Peter Hodgkinson’s Orwell Calling. “Pretty much everybody abided by the rules,” says Hamilton. “The job of the literary executor is to filter but you have to be pretty open-minded and alert. I was interested in quality control.”

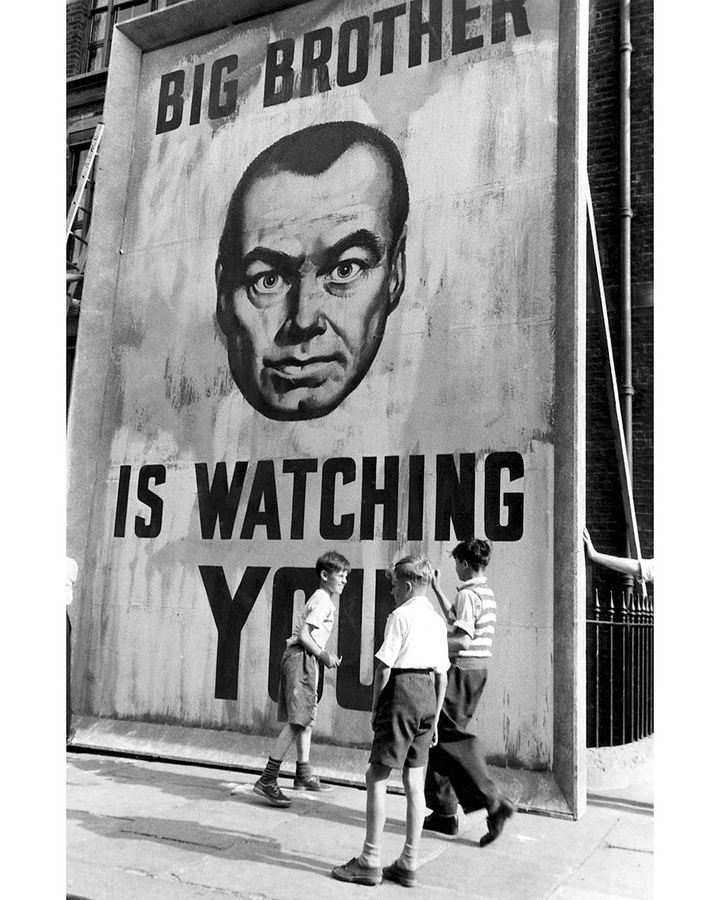

The phrase ‘Big Brother is watching you’ has been trademarked to ensure Orwell merchandise maintains a certain standard (Credit: Alamy)

The lapsing of copyright has triggered an avalanche of new editions from various publishers but not a total free-for-all. Letters and unpublished essays uncovered after Orwell’s death by the late scholar Peter Davison remain restricted. Hamilton has trademarked phrases such as “Big Brother is watching you” to ensure that Orwell merchandise continues to maintain certain standards, and to make money for the Orwell Foundation. And in the US, where copyright lasts for 95 years after publication, Animal Farm is protected until 2040, and Nineteen Eighty-Four until 2044. Given that many Trumpian conservatives are convinced the latter book speaks to them, perhaps that has saved us from a novel in which Joe Biden is a “woke” Big Brother.

Orwell-curious filmmakers face a steeper hurdle. Just days before her death, Sonia Orwell sold the movie rights to Chicago attorney Marvin Rosenblum, who produced Michael Radford’s adaptation in 1984. Even now, the US rights still reside with Rosenblum’s widow Gina. “So many suitors over the years have gone off to talk to her, and six months later they’ve come back pulling their hair out,” says Hamilton. A new version was in development for years with producer Scott Rudin and director Paul Greengrass, but its current status is unclear. “She has been unable to get a remake made, which I think is a scandal,” says Hamilton. “It’s a ridiculous waste of an opportunity.”

An unforgettable fictional world

Orwell wrote six novels, three classic works of non-fiction, and more than a million words of journalism, but in IP terms everything else is dwarfed by the twin peaks of his career: Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm. They are two very different books with a shared political agenda. First Orwell explained the rise of Soviet totalitarianism in the form of a farmyard allegory; four years later, he used dystopian science fiction to anatomise the methods of an all-powerful totalitarian state. One was a lesson from the recent past; the other a warning to the future. For as long as regimes seek to distort reality and suppress liberty, these books will have anxious readers.

Taylor recalls a recent event to promote his biography: “I said, ‘Put up your hand if you’ve read Nineteen Eighty-Four’, and 48 out of 50 hands went up. It was the same with Animal Farm. But nobody’s really read the earlier novels.” In the past three years there have been two new stage versions of Animal Farm, with Andy Serkis’s animated movie version currently in production after a decade of delays. Newman and Biles both suspected that there would be a flood of post-copyright Orwell novels but, so far, the only other attempt has been Katherine Bradley’s poorly reviewed The Sisterhood, another story about Julia. “I did feel a race against time,” says Biles. “Unnecessarily, it seems. It’s astonished me that we haven’t heard of similar things happening.”

With Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell constructed an unforgettable fictional world, but one riddled with mysteries. Some unanswered questions – does Big Brother really exist? Was Julia working for the Thought Police all along? – feel like strategic ambiguities. Others, such as the operation of the telescreen or details of life in the “prole district”, seem more like omissions. Perhaps Orwell decided that they were irrelevant to his mission of explaining the psychology of totalitarianism. Perhaps, because he was desperately ill with tuberculosis, and racing to finish the book between hospitalisations, he simply didn’t have the time or energy to plug the gaps. Then again, all novelists have their blind spots and weaknesses, so it’s possible that Orwell didn’t even register how much he had left unexplained.

Whatever the reasons, Orwell left many intriguing blank spaces in the world of Airstrip One. Sandra Newman says that Julia is an indelibly vivid character: “She feels like a real person, even though she doesn’t really add up. Maybe Winston wasn’t really in love with her, but Orwell probably was.” At the same time, Julia is an enigma, full of unrealised potential. “A lot of people find it frustrating that she’s supposedly in love with Winston, who is presented as an extremely unappetising person,” Newman says. “So there’s the question: what does she see in him? There are things I found unconvincing as true accounts of her life but convincing as things that a ‘cool girl’ would say to a man she’s trying to impress. Some things only make sense if you assume she’s not telling the truth. Orwell doesn’t give her enough credit. She’s a more genuine rebel in a lot of ways than Winston is.”

In the US, where copyright lasts for 95 years after publication, Animal Farm is protected until 2040, and Nineteen Eighty-Four until 2044 (Credit: Alamy)

Newman retells the events of Nineteen Eighty-Four from Julia’s point of view in the first two-thirds of her novel, before imagining what she might have done next after her brutal interrogation in the Ministry of Love. Through Julia’s eyes, the author illuminates previously unseen corners of Airstrip One. “I tried to make it all consistent with the actual words on the page so that you could read both books side by side and everything would interlock,” she says. “A lot of choices I made were the only possible choices that would work.”

A former Russian student who spent time in the USSR during the 1980s, Newman brings to Julia her own insights into life under Soviet communism as well as her perspective as a female reader. “There is a lot of expression of real anger towards women in the novel,” she says. “To me it was troubling. I’ve met a lot of people who actually couldn’t finish the book or who hated it because of that.” Nonetheless, she remains an admirer.”One thing that Orwell can’t be faulted on is his understanding of the psychology of totalitarianism. I was impressed by that pretty much every time I opened the book. I think that’s still true of authoritarian movements now. The shoe still fits.”

Creating something new

Adam Biles did not seek permission from the estate, so the issue of US publication is unresolved. On a literary level, too, he faced an entirely different challenge. A sequel rather than a retelling, Beasts of England introduces a new cast of animal characters several years after the events of Animal Farm, and satirises 21st-Century populism in the UK and elsewhere. While his first draft was the same length as Orwell’s book (“Adult readers have perhaps a certain level of patience for talking animals”), Biles found himself loosening his self-imposed rules from draft to draft.”I didn’t want it to be a reverential project, as if I was channelling Orwell,” he says. “I wanted to use the tools he created but do something new with them.”

Orwell was writing with a specific political purpose: to alert readers to the reality of Stalinism. Animal Farm is therefore a remarkably disciplined allegory of the history of the USSR, with key figures and events precisely mirrored by the animals of Manor Farm. Though fuelled by genuine anger with the British government, from austerity to Brexit to the mishandling of the pandemic, Biles felt that the mess of democratic politics required a more flexible approach: “Whenever I felt I was tacking too close to a particular character or event I’d try to find a way to diverge from that. Orwell saw very clearly what was happening in the USSR and found a way to describe that very clearly. I went into this almost from the opposite position of wanting to develop an understanding of what was happening.”

Animal Farm is a disciplined allegory of the history of the USSR, with key figures and events precisely mirrored by the animals of Manor Farm Animal Farm (Credit: Getty Images)

For all their differences, both Newman and Biles honour their debt to Orwell with the resonant clarity of their prose and their sense of moral purpose. DJ Taylor fears that Orwell’s classics will not always fall into such careful hands. He recalls being commissioned by the Wall Street Journal a decade ago to review recent novels about Sherlock Holmes. “Three crates of books came across the Atlantic, and they were bananas,” he says. “By this point Holmes had become a floating signifier – he could mean absolutely anything to anybody. I fear that Orwell may go that way. With Holmes you’ve only got the personality and the forensic ability whereas with Orwell you’ve got a set of political beliefs.” While Newman’s Julia is in the spirit of Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys’s celebrated 1966 prequel to Jane Eyre, how long will it be before someone writes something in the more cavalier vein of Seth Grahame Smith’s Austen-spoofing Pride and Prejudice and Zombies? Or a book that entirely travesties Orwell’s politics?

Perhaps, though, the act of explicitly reimagining a classic is not entirely distinct from what novelists do as a matter of course. “Novelists are quite parasitical in our approach to material, whether it’s our own lives or turning people we’ve met into characters,” says Biles. “There’s always an element of harvesting material and producing something new with it.”

“We underestimate how much a part of literature is rewriting existing literature,” agrees Newman. “You want to write something that says what the last book you read didn’t say. When you narrow it down to one book, the scales fall from your eyes, and you realise that that’s what you’ve been doing all along.”

Julia by Sandra Newman and Beasts of England by Adam Biles are out now.

Dorian Lynskey is the author of The Ministry of Truth, a biography of George Orwell’s 1984.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.