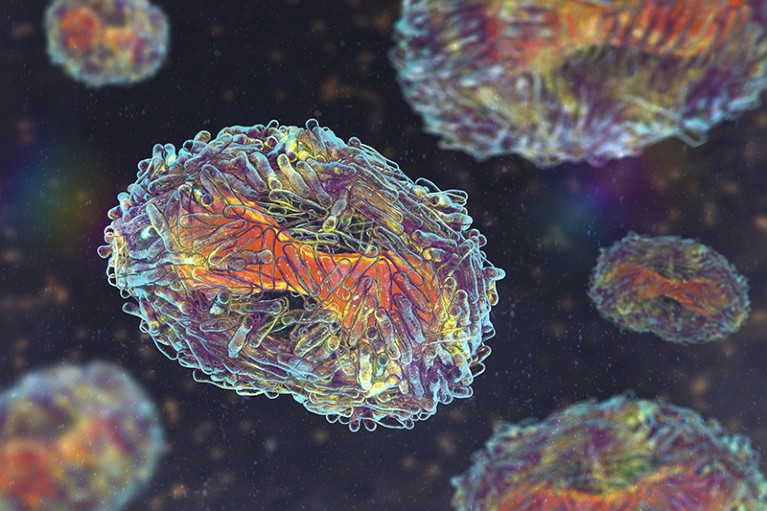

The monkeypox virus has been added to the WHO’s list of priority pathogens.Credit: Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty

The number of pathogens that could trigger the next pandemic has grown to more than 30, and now includes influenza A virus, dengue virus and monkeypox virus, according to an updated list published by the World Health Organization (WHO) this week. Researchers say that the list of ‘priority pathogens’ will help organizations to decide where to focus their efforts in developing treatments, vaccines and diagnostics.

“It’s very comprehensive,” says Neelika Malavige, an immunologist at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura in Colombo, Sri Lanka, who was involved in the effort. She studies the Flaviviridae family of viruses, which includes the virus that causes dengue fever.

The priority pathogens, published in a report on 30 July, were selected for their potential to cause a global public-health emergency in people, such as a pandemic. This was on the basis of evidence showing that the pathogens were highly transmissible and virulent, and that there was limited access to vaccines and treatments. The WHO’s two previous efforts, in 2017 and 2018, identified roughly a dozen priority pathogens.

“The prioritization process helps identify critical knowledge gaps that need to be addressed urgently,“ and ensure the efficient use of resources, says Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, who leads the WHO’s R&D Blueprint for Epidemics team that prepared the report.

It’s important to regularly revisit these lists to account for major global changes in climate change deforestation, urbanization, international travel and more, says Malavige.

The latest effort identified risky pathogens in entire families of viruses and bacteria, which broadened its scope.

Mpox and smallpox

More than 200 scientists spent some two years evaluating evidence on 1,652 pathogen species — mostly viruses, and some bacteria — to decide which ones to include on the list.

Among the more than 30 priority pathogens are the group of coronaviruses known as Sarbecovirus, which includes SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic — and Merbecovirus, which includes the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Previous lists included the specific viruses that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and MERS, but not the entire subgenuses that they belong to.

Other additions to the list include the monkeypox virus, which caused a global mpox outbreak in 2022, and continues to spread in pockets of Central Africa. The virus is deemed a priority, and so is it’s relative, the variola virus, which causes smallpox, despite it having been eradicated in 1980. This is because, owing to people no longer getting vaccinated routinely against the virus, and therefore not becoming immune to it, an unplanned release of it could cause a pandemic. The virus could potentially be used “by terrorists as a biological weapon”, says Malavige.

Half a dozen influenza A viruses are also now on the list, including subtype H5, which has sparked an outbreak in cattle in the United States. Among the five bacteria — all newly added — are strains that cause cholera, plague, dysentery, diarrhea and pneumonia.

Two rodent viruses have also been added because they have jumped to people, with sporadic human-to-human transmission. Climate change and increased urbanization could raise the risk of these viruses transmitting to people, according to the report. The bat-borne Nipah virus remains on the list because it is deadly and highly transmissible in animals, and there are currently no therapies to protect against it.

Many of the priority pathogens are currently confined to specific regions but have the potential to spread globally, says says Naomi Forrester-Soto, a virologist at the Pirbright Institute near Woking, UK, who also contributed to the analysis. She studies the Togaviridae family, which includes the virus that causes Chikungunya. “There isn’t really any one place that is most at risk,” she says.

‘Prototype’ pathogens

In addition to the list of priority pathogens, researchers also created a separate list of ‘prototype pathogens’, which could act as model species for basic-science studies and the development of therapies and vaccines. “This may encourage more research,” into less-studied viruses and bacteria, says Forrester-Soto.

For example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were no available human vaccines for any of the coronaviruses, says Malik Peiris, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong, who was part of the Coronaviridae research group. Developing vaccines for one member of the family will bring confidence to the scientific community that it is better placed to address a major public-health emergency for those viruses, he says. This applies to treatments, too, he says, because “many antivirals work across a whole group of viruses”.

Forrester-Soto says that the list of pathogens is reasonable given what researchers know about the viruses. But “some pathogens from the list may never cause an epidemic, and one we have not thought of may be important in the future,” she says. “We have almost never predicted the next pathogen to emerge.”.