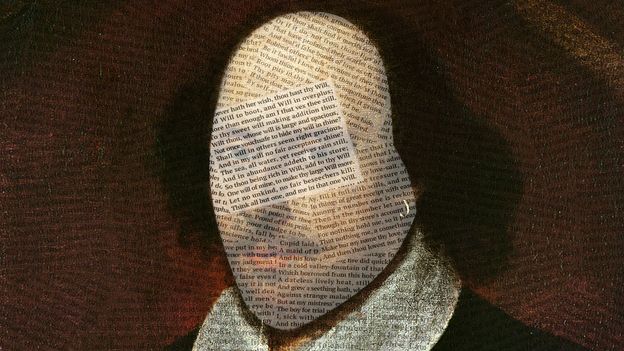

If the fact that William Shakespeare’s First Folio, that legacy-defining collection of his plays, is turning 400 has passed you by, you can be sure he’d have had a zinger of a putdown to sling your way. Or better yet, a whole string of them. “Thou art a boil, a plague sore, an embossed carbuncle in my corrupted blood” might just do it, borrowed from King Lear railing against his daughter, Goneril. Then again, perhaps he’d settle for more aloof damnation, along the lines of Orlando’s insult to Jaques in As You Like It: “I do desire we may be better strangers.”

That isn’t a wish likely to be granted to Shakespeare himself any time soon. During his 52 years on Earth, he enriched the English language in ways so profound that it’s hard to fully gauge his impact. Without him, our vocabulary would be just too different. He gave us uniquely vivid ways in which to express hope and despair, sorrow and rage, love and lust. Even if you’ve never read one of his sonnets or seen one of his plays – even if you’ve never so much as watched a movie adaptation – you’re likely to have quoted him unwittingly. Speak the English language, and he’s impossible to avoid.

More like this:

– How Shakespeare ‘invented humans’

– The overlooked star of Orwell’s 1984

– How modern readers get this epic wrong

That’s in part because fellow artists draw so readily on him in their paintings, operas and ballets. Shakespeare’s influence is evident in pop culture as well: singer-songwriter Nick Lowe’s 1970s earworm, Cruel to be Kind, took its title from lines Hamlet addressed to his mother. “I must be cruel only to be kind,” the Prince of Denmark tells her in a wriggling kind of apology for killing a courtier and meddling in her new relationship. Hamlet also yielded the title of Agatha Christie’s theatrical smash, The Mousetrap, Alfred Hitchcock’s evocative spy thriller, North by Northwest, Ruth Rendell’s Put on by Cunning, Philip K Dick’s Time Out of Joint, and Jasper Fforde’s Something Rotten.

It’s not just Hamlet, either. Sticking with latter-day minstrels, when Iron Maiden named their song Where Eagles Dare, they were borrowing a phrase from Richard III. Then there’s Tupac Shakur’s Something Wicked, a nod to a couplet uttered by one of the witches in Macbeth.

Famous phrases

These catchy titles barely gesture to Shakespeare’s influence on the minutiae of our lives. If you’ve ever been “in a pickle”, waited “with bated breath”, or gone on “a wild goose chase”, you’ve been quoting from The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice and Romeo and Juliet respectively.

Next time you refer to jealousy as “the green-eyed monster”, know that you’re quoting Othello’s arch villain, Iago. (Shakespeare was almost self-quoting here, having first touched on green as the colour of envy in The Merchant of Venice, where Portia alludes to “green-eyed jealousy”.)

Allow yourself to “gossip” (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), and you’re quoting him. “The be-all and end-all” is uttered by Macbeth as he murderously contemplates King Duncan, and “fair play” falls from Miranda’s lips in The Tempest. And he even invented the knock-knock joke in the Scottish play.

Some phrases have become so enduringly well-used that they’re regarded as clichés – surely a compliment for an author this long gone. “A heart of gold”? You’ll find it in Henry V, while “the world’s mine oyster” crops up in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Life imitates art

His impact endures not only in the way we express ourselves, but how we experience and process the world around us. Had Shakespeare not given us the words, would we truly feel “bedazzled” (The Taming of the Shrew)? Had he not taught us the word “gloomy” (Titus Andronicus), would that particular shade of despondency be a feeling we recognised? And could we “grovel” effectively (Henry VI, Part II) or be properly “sanctimonious” (The Tempest) had he not shown us how?

Back in 2008, two antiquarian booksellers in the US, George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, declared that they’d found the dictionary Shakespeare used. The book, which they bought on eBay, was a copy of John Baret’s Alvearie, a popular late-16th-Century dictionary in four languages. It’s densely annotated throughout but the clincher, they claim, is the handwritten “word salad” on the tome’s blank back page, a sheet filled with a mix of French and English words, some of which ended up in Shakespeare’s plays. They’ve gone on to publish a book about it, Shakespeare’s Beehive, but their claims as to the dictionary’s provenance remain contentious.

Victorian word expert F Max Muller estimated that Shakespeare used 15,000 words in his plays and poems, a portion of which he invented himself by merging existing words and anglicising vocabulary from foreign languages, changing nouns into verbs, and adding prefixes and suffixes. By contrast, Milton used a mere 8,000, and the Old Testament is made up of only 5,642. Meanwhile, an unschooled agricultural worker of the day would supposedly have said all that he had to say in fewer than 300 words.

It’s now thought that Shakespeare used in excess of 20,000 words, and of those that were his own conjuring, many have become indispensable. Imagine not having the word bedroom, for example (that one cropped up for the first time in A Midsummer Night’s Dream). And what about “eyeball” (Henry VI Part 1), “puppy dog” (King John), “hurry” (The Comedy of Errors), “jaded” (Henry VI Part 2) or “kissing” (Love’s Labour’s Lost)?

Dispute simmers on among lexicographers over just how many words and phrases Shakespeare actually coined, and how many he merely popularised by bedding them down in a memorable plot and vivid sentences. In recent years, academics have harnessed digital resources, simultaneously searching thousands of texts and concluding that his contribution to the English language has been overestimated.

In 2011, Ward EY Elliott and Robert J Valenza of America’s Claremont McKenna College published a paper arguing that new words attributed to Shakespeare have probably been over-counted by a factor of at least two. Dr David McInnis, a Shakespeare professor at the University of Melbourne, has since accused the early compilers of the first Oxford English Dictionary of “bias”, saying they preferred famous literary sources when it came to finding examples of a word’s first usage. He’s also noted that, as a writer, Shakespeare would have wanted his audience to understand him, so most of the words he used would have been in circulation already.

The OED increasingly reflects this: in the mid-20th Century, Shakespearean language expert Alfred Hart estimated Shakespeare’s tally of first citations stood at 3,200. Today, thanks in part to the greater availability of texts searchable by computers, that figure has dropped to around 1,700.

In some ways, this makes Shakespeare’s flair and originality all the more impressive. His linguistic arsenal didn’t perhaps dwarf that of his contemporaries, and yet how he used it. His are the stories, the lines we remember. Not that 1,700 words is bad going for a lexical experimenter, especially when so many of them saturate our everyday speech.

How did he manage it, you might wonder? It’s partly his turn of phrase. Would “fashionable” have caught on had he not set it in such a wry sentence as this in Troilus and Cressida? “For time is like a fashionable host, that slightly shakes his parting guest by th’ hand.”

Then there’s the fact that these words are voiced by some unforgettable characters – men and women who, despite the extraordinary situations in which they tend to find themselves, are fully and profoundly human in both their strengths and frailties. It’s little wonder that critic Harold Bloom titled his 1998 book on the man Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. If the mark of a great writer is that they’re still read, then perhaps the mark of an ingenious one is that they’re still spoken, too.

This article was originally published in 2014.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.