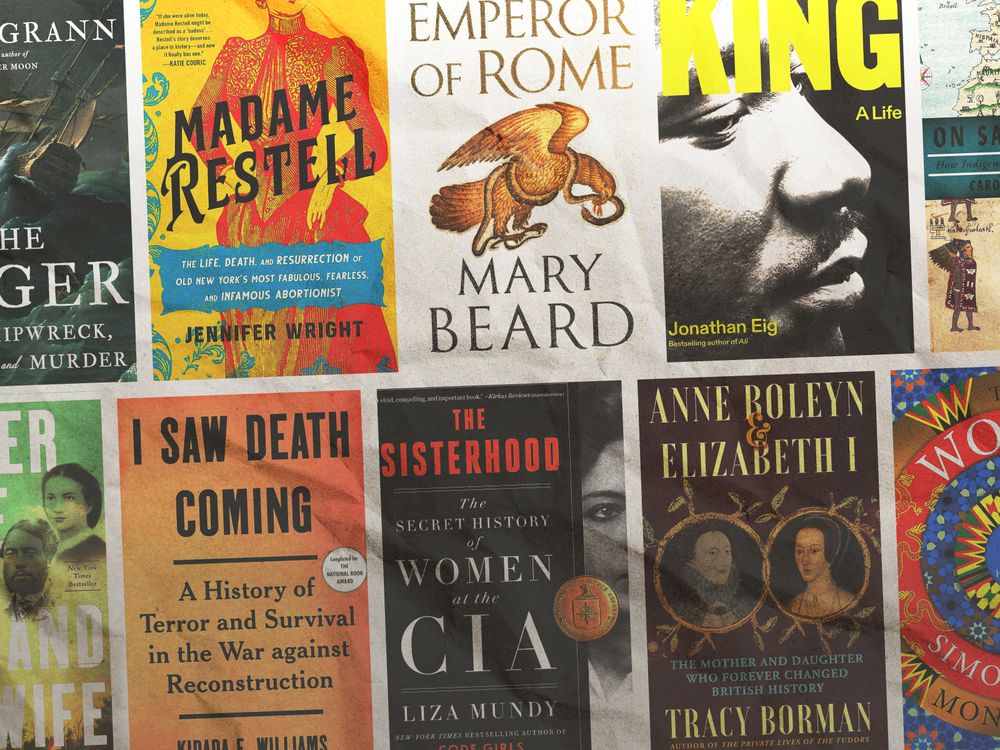

Smithsonian‘s picks for the best history books of 2023 include King: A Life, The Sisterhood and The Wager.

Illustration by Emily Lankiewicz

For many, 2023 was a year of momentous change and loss, marked by events that will be chronicled in history books for generations to come. Longstanding tensions in the Middle East erupted when Hamas invaded Israel on October 7 and have continued to reverberate through the Israeli counterattack and humanitarian crisis in Gaza. To the north, the Russia-Ukraine war entered its second year, continuing a conflict that shows few signs of slowing.

In the United States, book bans in public schools and libraries spoke to the growing debate over how history—especially the nation’s long history of racial inequality—is taught. The conversation reflects not only broader divisions in an increasingly polarized country, but also a push to redefine the very nature of the discipline. “Most of our prior arguments were about who to include in the story, not the story itself,” Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania, told the Washington Post earlier this year. “America has lost a shared national narrative.”

This year, the ten history books we’ve chosen to highlight served a dual purpose. Some offered a respite from reality, transporting readers to places like ancient Rome and Tudor England. Others reflected on the fraught nature of the current moment, detailing how the nation’s past—including white supremacist violence during Reconstruction and the history of restrictions on women’s reproductive rights—informs its present and future. From a biography of Martin Luther King Jr. to the story of a deadly shipwreck, these are some of Smithsonian magazine’s favorite history books of 2023.

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann

David Grann’s newest page-turner, The Wager, has much in common with his 2017 book, Killers of the Flower Moon, which was recently adapted for the screen by Martin Scorsese. Both tell the tale of a once-infamous, now more obscure chapter in history, resurrected through meticulous research and a gift for immensely readable prose. Just as the Reign of Terror, a string of murders that struck the Osage Nation in the early 20th century, was more widespread than an FBI investigation suggested, the circumstances surrounding the 1741 wreck of the HMS Wager were more mysterious than survivors initially claimed.

A Royal Navy ship that set sail from England in 1740, its crew tasked with pursuing an enemy galleon during a war with Spain, the Wager ran aground off the coast of Patagonia in 1741. A few years after the shipwreck, two sets of sailors returned home, each with their own competing version of events—one a story of survival under horrific conditions and the other a harrowing account of mutiny, a crime then punishable by death.

To untangle this web of contradictions, Grann, a longtime staff writer at the New Yorker, “spent years combing through the archival debris: the washed-out logbooks, the moldering correspondence, the half-truthful journals, the surviving records from the troubling court-martial,” as he explains in an author’s note. Grann frames his tale as a mystery, though he leaves readers to draw conclusions for themselves; the result is a tour-de-force book that will leave readers satisfied while prompting them to consider larger questions of imperialism and the notion of truth itself.

Madame Restell: The Life, Death and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless and Infamous Abortionist by Jennifer Wright

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, Jennifer Wright was putting the finishing touches on her latest book, Madame Restell, a biography of the woman she deems “a businesswoman, a scofflaw, an immigrant and an abortionist [who] made men really, really mad.” The timing of the decision wasn’t lost on Wright, a journalist and author of pop-culture history books. It “disabuses us of the notion that we’ve come as long a way in our treatment of women as we liked to imagine we did,” she says in a statement. “A lot of people have talked about how we went back 50 years with the Dobbs ruling. I would say we went back 150,” to the 1870s.

By that decade, Restell had been offering abortions for more than 30 years. Born Ann Trow in England in 1811, she immigrated to the U.S. with her husband and daughter in 1831, only to find herself a widowed single mother just two years later. By a stroke of luck, she formed a connection with a neighbor who taught her how to compound pills and likely showed her how to provide surgical abortions when the abortifacient drugs she gave patients failed. With the help of her brother and her second husband, Trow developed a new persona, Restell, and started advertising her “celebrated preventative powders for married ladies whose health prevents too rapid an increase of family.” This straightforward acknowledgement of the nature of Restell’s services—risky at a time when abortion was a criminal offense in New York—attracted both satisfied customers and powerful enemies, among them the anti-vice activist Anthony Comstock, who would eventually bring about the abortionist’s downfall.

This biography presents a searing portrait of an indomitable woman, examining the experiences that shaped Restell’s career choice and the challenges she overcame, including multiple arrests and a stint in prison. Wright juxtaposes her subject’s story with those of Restell’s patients and an overview of the broader conversation surrounding abortion in the late 19th century.

Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I: The Mother and Daughter Who Forever Changed British History by Tracy Borman

Tracy Borman is a prolific chronicler of Tudor England, with each of her books offering a novel take on the world’s most-discussed dynasty. In recent years, she’s examined the male influences in Henry VIII’s life and the private lives of the Tudors, from their romps in the bedroom to their bathroom habits. Now, Borman—an author who serves as joint chief curator of England’s Historic Royal Palaces—has turned her attention to the relationship between Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I, a mother and daughter who she says “changed the course of British history.”

Anne was Henry’s second wife, a strong-willed, worldly woman whose refusal to become the king’s mistress pushed him to break with Rome and launch the English Reformation. Her time on the throne was brief, ending with her execution in 1536, but she left behind a daughter, the future Elizabeth I. Popular lore suggests Elizabeth, who was just 2 years old when her mother was beheaded, rarely acknowledged Anne, whose existence was all but erased by Henry after her death. When Elizabeth took the throne in 1558, she didn’t actively attempt to restore Anne’s reputation by overturning the annulment of her marriage or moving her body from a chapel at the Tower of London.

“The obvious conclusion is that Elizabeth was at best indifferent toward, and at worst ashamed of, Anne,” writes Borman. “But the truth is both more complex and more fascinating. Exploring Elizabeth’s actions both before and after she became queen reveals so much more than her words.” Evidence laid out in the book points to Elizabeth’s enduring love for Anne, whose push for religious reform reached new heights during her daughter’s reign. Borman suggests Elizabeth fulfilled a request made by Anne on the scaffold: “If any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best.”

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig

In his biography of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr., Jonathan Eig follows the winning formula laid out in his 2017 book, Ali: A Life, using an impressively researched deep dive to present a more nuanced portrait. “In the process of canonizing King,” Eig writes, “we’ve defanged him, replacing his complicated politics and philosophy with catchphrases that suit one ideology or another.”

Eig argues that contemporary observers have “mistaken King’s nonviolence for passivity” and “failed to recall that [he] was one of the most brutally divisive figures in American history.” Though he’s lionized today, King was widely disliked at the time of his assassination in 1968, attracting the disapproval of Southern segregationists, the government, militant Black activists and white liberals alike. Some thought he’d gone too far in his calls for equality; others said he hadn’t gone far enough. By reframing King’s life in a more realistic light, Eig seeks to “recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography,” showing his strengths, like the power of his speeches, and his weaknesses, from his numerous affairs to his penchant for committing plagiarism.

A magisterial addition to the literature on King, Eig’s book is a clear-eyed, sympathetic tribute to a man who reshaped America in just 13 years, bringing “the nation closer than it had ever been to reckoning with the reality of having treated people as property and secondary citizens,” as the author writes. Based on newly declassified FBI papers, more than 200 interviews and a trove of previously unpublished archival materials, King: A Life is poised to replace David J. Garrow’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1986 book, Bearing the Cross, as the standard biography of the activist. Garrow acknowledges as much in a review for the Spectator, praising Eig’s work as “the best-informed account of this deeply courageous, yet also deeply flawed, life.”

King: A Life

Vividly written and exhaustively researched, Jonathan Eig’s “King: A Life” is the first major biography in decades of the civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr.―and the first to include recently declassified FBI files.

The Sisterhood: The Secret History of Women at the CIA by Liza Mundy

Liza Mundy’s newest is a worthy successor to her 2017 best seller, Code Girls, which explored the stories of the unheralded American women who served as code breakers during World War II. The Sisterhood offers a comprehensive exploration of a similarly understudied topic: women at the CIA. Though women have worked at the agency since its founding in 1947, Mundy, a journalist and former Washington Post staffer, argues that their contributions have long been overlooked, in part due to the secretive nature of the job but also because of sexism.

From Jeanne Vertefeuille, a typist-turned-investigator who exposed the most damaging mole in CIA history, to Heidi August, who witnessed the 1969 coup in Libya and the Cambodian Civil War firsthand, The Sisterhood shows how “women made contributions not despite their gender but because of it, using their sex to move around the world unremarked,” as Mundy writes in an author’s note. Beyond the women who worked at the CIA, the book profiles individuals on the periphery of the organization, like Shirley Sulick, the Black wife of a white agent, who enjoyed surveilling KGB operatives during trips to the store and making dead drops by pretending to pick up items that had fallen out of her purse.

Based on more than 100 interviews, published histories, academic articles, declassified documents and personal writings, The Sisterhood is a deeply researched, exhaustive read spanning seven decades of CIA history. “Women were behind numerous intelligence ‘wins’ that have never seen the light of day, and [they] made points, papers and predictions that more attention should have been paid to,” Mundy writes. At the same time, the journalist acknowledges the harm women have done as participants “in some of the agency’s darkest, most controversial chapters.”

The Sisterhood: The Secret History of Women at the CIA

The acclaimed author of “Code Girls” returns with a history of three generations at the CIA, “electric with revelations” about the women who fought to become operatives, transformed spycraft and tracked down Osama bin Laden.

Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey From Slavery to Freedom by Ilyon Woo

The story of Ellen and William Craft, a couple who escaped slavery in 1848 by disguising themselves as an ailing white planter and his enslaved attendant, has received renewed attention in recent years, inspiring a short film, a children’s book and several academic studies. But it’s Ilyon Woo’s biography of the Crafts, Master Slave Husband Wife, that’s poised to become the authoritative account of their journey to freedom.

Born to a white planter and an enslaved woman, Ellen fell in love with William, an enslaved cabinetmaker, while working in the Georgia home of her white half-sister. The couple hatched an escape plan, taking advantage of Ellen’s white-passing appearance to transform themselves into an unassuming duo: a master and his servant. Ellen dressed as a man, wore a sling on her arm to avoid being asked to write, applied poultices to her neck to indicate she had trouble speaking and wore hand-sewn clothing that spoke to her supposed high status. Traveling via train and steamship, the Crafts reached the free state of Pennsylvania on Christmas Day, after several close calls. They briefly found fame on the abolitionist speaking circuit, but following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, they fled to the United Kingdom. While living abroad, they wrote a book about their escape, though Woo points out that William downplayed Ellen’s role, claiming sole authorship of the text and referring to her only as his wife.

Master Slave Husband Wife is meticulously sourced, with “every description, quotation and line of dialogue” coming from historical materials, according to Woo. Yet the author’s prose is novelistic, immersing readers in the escape through descriptions of the “gentleman’s drawers” Ellen wore as part of her disguise and the tools of torture that awaited enslaved people at the Sugar House in Charleston, South Carolina, where the couple stopped on their way to Philadelphia. The dangerous voyage was “very cinematic,” Woo tells NPR. “Whenever I got stuck in trying to figure out how to tell this story, I sort of tried to picture: where would the camera move, and which camerapeople am I going to use in terms of the angles that I’ll get into the story?”

I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction by Kidada E. Williams

Reconstruction, the government-sanctioned push to reunite the nation in the aftermath of the Civil War, is often deemed a failure by historians. The federal government gave Southerners significant freedom to choose how they wanted to rebuild; rebellious states responded by passing laws that limited the rights of Black Americans and establishing white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Given the systematic nature of this campaign against Black Americans, historian Kidada E. Williams believes that classifying Reconstruction as a failure is an oversimplification. “Black Reconstruction didn’t ‘fail,’ as so many are taught,” she writes in I Saw Death Coming. “White Southerners overthrew it, and the rest of the nation let them.”

Williams’ painstakingly researched book centers firsthand testimony from Black Americans, as recorded in transcripts from a congressional investigation into the KKK; affidavits provided to the Freedmen’s Bureau; interviews given to the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s; newspaper articles; and personal papers. Though these sources have long been available to historians, Williams approached them from a new perspective, focusing on “African Americans’ efforts to articulate what their families had gained with Reconstruction (what they had achieved with freedom and the expansion of democracy) and what they had lost and were losing to racist violence,” as she tells the Detroit Free Press.

I Saw Death Coming is a timely, incisive read at a time when white nationalism is on the rise, even as many Americans take steps to confront systemic racism in the U.S. Instead of attributing Reconstruction-era violence to “pockets of white resistance,” Williams suggests that “a kind of crypto-Confederacy emerged from the collective rage of a fallen white South that refused to cede an inch to those they had subjugated,” notes the Los Angeles Times in a review. “White Southerners did not seek to completely exterminate all African Americans,” Williams argues, “but the successive violence they used, rejecting newly freed people’s right to any rights, was genocidal-like in nature.”

The World: A Family History of Humanity by Simon Sebag Montefiore

“The family,” writes Simon Sebag Montefiore in The World, “remains the essential unit of human existence.” From the Egyptian king Khufu and his mother to the “conquering family” of Genghis Khan, the Habsburg and Romanov dynasties, and the Roosevelts, Montefiore’s sweeping history traces the trajectory of the world through the relatives who ruled over it. Some of his subjects are household names, but many others are lesser known to many readers in the U.S., among them Jacques I of Haiti, the Mughal Emperor Babur and Chinese Empress Wu.

The historian’s sweeping exploration captures the complicated nature of family dynamics, particularly when politics is involved. He details acts of violence against relatives, including Ptolemy IV’s dismemberment of his son and Kim Jong-un’s likely murder of his brother; battles over succession rights among heirs; political marriages in which parents sent their daughters “to marry strangers in faraway lands where they then die[d] in childbirth”; and (comparatively rare) heartwarming moments between loved ones. The portrait that emerges is one of dysfunction, with the pitfalls of hereditary power, whether formalized or embodied by political dynasties like the Kennedys, readily apparent.

Packed with memorable anecdotes and lurid details, The World focuses less on how family units have evolved over time than on the stories of families throughout history. This approach succeeds in large part because of the encyclopedic depth of Montefiore’s research evident throughout the book’s 23 chapters and 1,344 pages. “In every family drama, there are many acts,” the historian writes. “That is what Samuel Johnson meant when he said every kingdom is a family and every family a little kingdom.”

On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe by Caroline Dodds Pennock

Books about the Age of Exploration tend to focus on the Europeans who journeyed to the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Historian Caroline Dodds Pennock opted for a different approach, reversing focus to discuss the tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans who traveled to Europe between 1492, when Christopher Columbus supposedly “discovered” the New World, and 1607, when the colony of Jamestown was founded.

“These overlooked multitudes of Indigenous travelers—nobles, diplomats, servants, translators, families, entertainers, enslaved people—overturn our understandings of early modern exploration and empire,” writes Pennock in On Savage Shores. “And the vast network of global connections they inhabited … sowed the seeds of our cosmopolitan modern world more than a century before” the Mayflower landed in Massachusetts in 1620.

Pennock’s book draws on archival records to tell the stories of a diverse group of Indigenous people, including Martín Cortés, the mixed-race son of conquistador Hernán Cortés, who “lived the life of a young Spanish nobleman, essentially,” as Pennock told Smithsonian earlier this year; Guaibimpará (Catherine du Brasil), a Brazilian woman who settled in France with her husband, a shipwrecked Portuguese sailor, in 1528; and Diego de Torres y Moyachoque, a cacique, or tribal chief, who traveled to Spain on a diplomatic mission in 1575.

Many of Pennock’s subjects are anonymous, their names unrecorded in European sources that offer limited glimpses of their lives. But the historian deftly navigates these gaps in the archives, interrogating the colonialist bias of the records available to present a fuller portrait of cultural exchange at a pivotal moment in world history. As historian David Olusoga puts it in a review for the Guardian, On Savage Shores is a “work of historical recovery.”

Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World by Mary Beard

Classicist Mary Beard follows up her epic 2015 history of ancient Rome, SPQR, with a more intimate discussion of the empire’s rulers. As Beard writes in the book’s introduction, Emperor of Rome “explores the fact and fiction, … asking what [rulers] did, why they did it and why their stories have been told in the extravagant, sometimes lurid, ways that they have.” In addition to addressing “power, corruption and conspiracy,” the book asks what these individuals’ everyday lives were like, from what and where they ate to whom they slept with and how they traveled.

Beard begins her narrative with Elagabalus, a Syrian teenager who took the throne at age 14 and was murdered just four years later, in 222 C.E. The emperor is better known for his banquets than his achievements as a ruler: Ancient chronicles claim he forced guests to sit on whoopee cushions; served fake food crafted from wax or glass; and released tame animals in rooms occupied by hungover attendees, who died of fright upon waking up face to face with a lion, leopard or bear.

As entertaining as these anecdotes are, historians generally agree that they’re grossly exaggerated, concocted by those eager to win the favor of Elagabalus’ successor. Though these stories are unreliable, Beard argues that they open a window into “the anxieties that surrounded imperial rule,” chief among them “the terror of power without limits.” The scholar also uses archaeological evidence to examine the veracity of ancient accounts; as she points out, the limited nature of cooking facilities at Hadrian’s Tivoli villa contradicts the suggestion that feasts featuring peacock brains and flamingo tongues were regular occurrences there.

The biggest question posed by Emperor of Rome is why some rulers are considered good and others bad. The answer, according to Beard, comes down to succession. Roman emperors didn’t simply pass on the throne to their eldest son, as generations of European rulers would later do. Instead, they designated a successor, who could be a relative but was often not. Whether this individual ultimately claimed the title—and what happened when emperors failed to name an heir—was an entirely different issue, and “the transition of power was almost always debated, fraught and sometimes killed for,” writes Beard. “Once the old ruler was dead, it was others who could turn, or refuse to turn, the implied promises of succession into reality.”

The emperors deemed successful, the classicist concludes, were the ones succeeded by their chosen successor, who was “almost bound to invest heavily in honoring the man who had put him there, and on whom his right to rule depended.”

Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World

“Emperor of Rome” goes directly to the heart of Roman fantasies (and our own) about what it was to be Roman at its richest, most luxurious, most extreme, most powerful and most deadly, offering an account of Roman history as it has never been presented before.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Recommended Videos