The month of June and the first few days of July were hotter than any in recorded history, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Residents in the south of the US and southern Europe have been enduring sweltering temperatures, bringing excessive heat warnings, wildfires and plummeting air quality. However, records are not just being broken on land – but in the water.

Global ocean sea surface temperatures were higher than any previous June on record, according to a report by the Copernicus Climate Change Service, with satellite readings in the North Atlantic in particular “off the charts”. Last month also set a record at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for the biggest difference between expected and actual sea surface temperatures.

Water temperatures around Florida, in particular, have been particularly warm. Scientists have also been tracking a large ongoing marine heatwave off the west coast of the US and Canada since it formed in May.

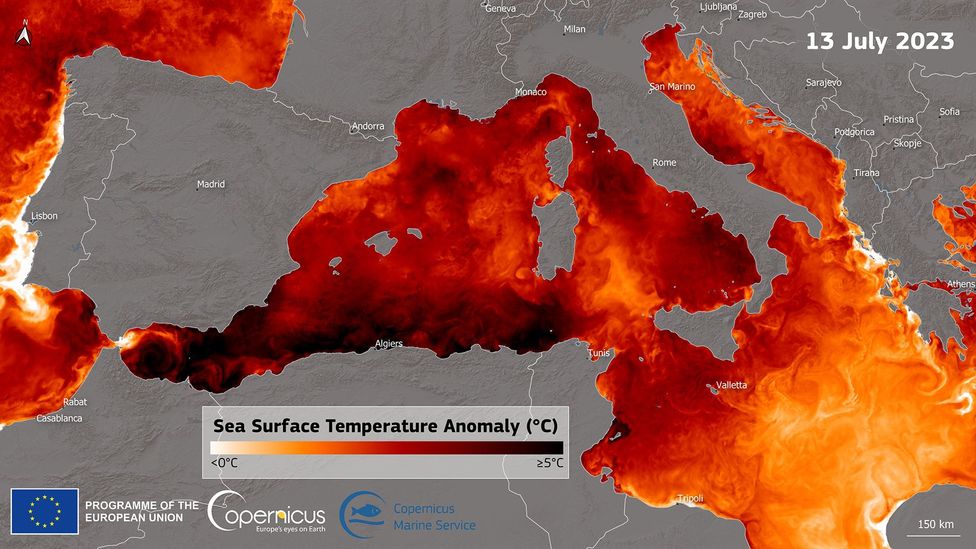

While the heatwave has since lessened in the north-east Atlantic, according to non-profit science organisation Mercator Ocean International, another in the western Mediterranean now appears to be intensifying, particularly around the Strait of Gibraltar. This week, sea surface temperatures along the coasts of Southern Spain and North Africa were 2-4C (3.6-7.2F) higher than they would normally be at this time of year, with some spots 5C (9F) above the long-term average.

Extreme marine temperatures have also recently been observed around Ireland, the UK and in the Baltic Sea, as well as areas near New Zealand and Australia. More recently, scientists suspect a possible heatwave south of Greenland in the Labrador Sea.

“We are having these huge marine heatwaves in different areas of the ocean unexpectedly evolve very early in the year, very strong and over large areas,” says Karina von Schuckmann, an oceanographer at Mercator Ocean.

The northern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea have experienced record-breaking sea temperatures over the past few months (Credit: European Union/Copernicus)

Carlo Buontempo, director of the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, says scientists expect big temperature variations in the Pacific Ocean associated with the El Niño weather pattern, a phase of planet-warming weather which is just beginning, although NOAA is monitoring a large heatwave in the Gulf of Alaska that has been sitting offshore since late 2022. (Read more from BBC Future about what another El Niño will mean for you.)

But what we’re currently seeing in the North Atlantic is “truly unprecedented”, says Buontempo.

Scientists are still trying to unravel its full causes.

Short-term changes in regional atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns can provide the conditions for periods of intense heat in the sea lasting for weeks, months or even years.

But long-term increases in ocean temperature driven by an increase in greenhouse gas emissions are a key factor in recent heatwaves. About 90% of excess heat generated by anthropogenic climate change has been stored in the ocean, and the past two decades have seen a doubling in the rate of heat accumulating in the Earth’s climate system.

You might also like:

- The simple ways cities can adapt to heatwaves)

- The fiery row behind Europe’s mythological heatwave names

- Will Texas become too hot for humans?

A 2021 expert report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found marine heatwaves doubled in frequency between 1982 and 2016, and have become both more intense and longer since the 1980s.

Another potential contributing factor is the volume of aerosols in the atmosphere, which have a slight cooling effect but appear to have dropped as a result of a drive to clean up the shipping industry. More recently, there has been an unusual lack of dust blown from the Sahara, which also normally has a cooling impact.

The current marine heatwaves could even get worse. While experts do not think El Niño itself was a driver of the North Atlantic event, the WMO expects it to add fuel to wider ocean heating.

Experts are concerned because marine heatwaves can affect ocean life, fisheries and weather patterns.

Record high temperatures along the Western Australian coast during the summer of 2010/2011 resulted in “devastating” fish mortality and destroyed kelp forests, fundamentally changing the coastal ecosystem. Several years later, an unprecedented marine heatwave caused by climate change and amplified by a strong El Niño caused the worst coral bleaching ever seen on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016.

Marine heatwaves can trigger mass coral bleaching events and have already been increasing the stress that reef ecosystems are under around the world. The high termpeatures can cause the coral polyps to expel the zooxanthellae living inside their tissue, causing them to turn white and leaving them more vulnerable to disease and other threats.

In the Mediterranean Sea, exceptional temperatures over the 2015-19 period led to repeated mass deaths of key species such as corals and seaweed. One recent study described marine heatwaves such as these as “pervasive stressors to marine ecosystems globally”.

Marine heatwaves are also making it easier for invasive species to thrive. Japanese kelp, for example, proliferated in New Zealand when a marine heatwave in 2017-2018 in the Tasman Sea killed off native southern bull kelp in the area.

Dan Smale, a marine ecologist at the UK’s Marine Biological Association and a member of the Marine Heatwaves International Working Group, says “short, sharp shocks” do not give species time to redistribute and those at the limit of temperatures their bodies can cope with are particularly at risk. But even around the UK coastline, which is not considered to be an extreme environment and where scientists expect ecosystems to gradually change, a marine heatwave could end up being lethal if it continues through the summer.

However, there is still a lot to learn about the impact of marine heatwaves compared with those on land because monitoring is more difficult and there is a lack of long-term records, says Smale. “The data we get from satellites since the early 1980s has been amazing… but the problem is trying to then go deeper,” he says.

High water temperatures can destroy vital marine habitats such as kelp forests, which offer sanctuary and provide food for many fish species (Credit: Getty Images)

A significant drop in phytoplankton has already been seen in the western North Atlantic, which Mercator Ocean attributes to the recent heatwave. This spring bloom is crucial because it provides most of the energy needed to sustain the region’s marine food chain and makes a substantial contribution to global ocean CO2 uptake.

The economics of regional fisheries could be affected too. A 2012 heatwave over the north-west Atlantic led marine species that favour warm water to move northwards and migrate earlier, changing when and how much seafood could be caught.

The North Atlantic is also a key driver of extreme weather. High sea surface temperatures can fuel hurricanes, although whether the developing El Niño will exacerbate or dampen this effect over the next year remains to be seen. Further inland, the warmth of the North Atlantic is the most important factor behind the alternating cycle of drought and heavy rain in central Africa.

More broadly, experts say the persistence of recent marine heatwaves is a worrying sign about how climate change is unfolding, alongside heatwaves on land, unusual melting of snow cover in the Himalayas and a loss of sea ice. Von Schuckmann notes that, even if humans stopped pumping CO2 into the air tomorrow, the oceans would continue to warm up for many years yet. “I am concerned as a climate scientist that we are further than we thought we are.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.