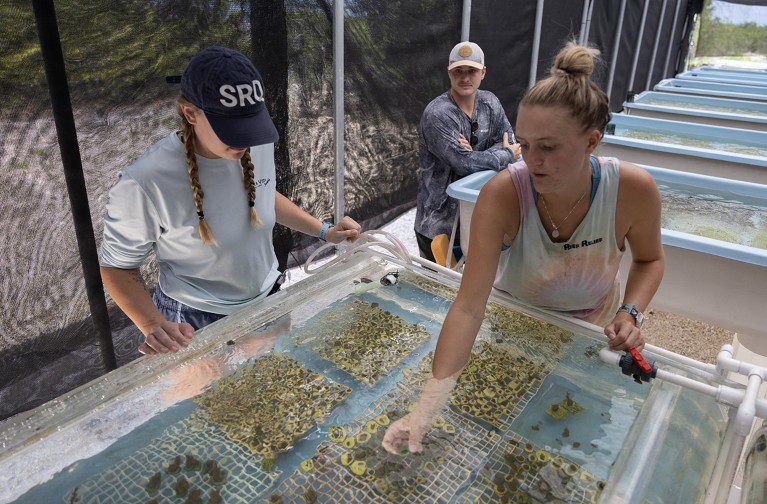

Alternative systems of recognition might be needed for support staff in research, such as (left to right) intern Izabela Burns and coral-restoration technicians Logan Marionn and Chloe Spring at the Million Corals Foundation farm in Summerland Key, Florida.Credit: Joe Raedle/Getty

Merit in science is usually measured by authorship. However, there are people who make invaluable contributions to science, whose names are never included in author lists. They are the unsung heroes of science; its communicators, administrators, illustrators and technicians.

There are growing calls to give such individuals more recognition. But what type of credit do they want, and how can the institutions that employ them ensure that their contributions are acknowledged?

Nature Index asked three senior science-support staff members for their views on how to recognize others in their fields.

GUSTAV CEDER: Explore parallel merit systems for support staff

Communications director for the Human Protein Atlas at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

People in different roles want to be credited in different ways. What drives me as a communicator is when the research that I’m working with is recognized by people outside the study’s field. Positioning great science in a creative and strategic manner, in the context of the real world, is a huge incentive for me.

The project that I’m working on now, the Human Protein Atlas, aims to map all of the proteins in human cells, tissues and organs and make the data open access. The project started in 2003, and there have since been more than 700 people involved — not just scientists, but also laboratory technicians, information–technology professionals and communicators, such as myself.

Nature Index 2023 annual tables

This pioneering project has included science-support workers, such as technical-staff members and lab engineers, as authors on peer-reviewed articles. I feel that this inclusive approach to teamwork benefits the production of knowledge and research excellence.

But I think more can be done to recognize the contributions of science-support staff. For example, in addition to the academic citations-based system, alternative metrics, or altmetrics, could be used to track the societal impact and influence of research through social media, news sites and other outlets, and give credit to those who bring scientific findings to a wider audience. I am currently evaluating new impact-tracking methods, such as Sage Policy Profiles, a free tool that tracks citations made by governments, think tanks and policymakers worldwide to scientific publications. Such tools could help to highlight the roles of support staff.

Taking a specific article and linking it to a specific real-world use is a complex task. But if we can identify, communicate and incentivize research impact — including acknowledging everyone who was involved in the work — it will help to secure future talent in supporting roles.

Anna Matros-Goreses advises universities to highlight career-growth opportunities for professionals in research administration.Credit: Courtesy of Anna Matros-Goreses

ANNA MATROS-GORESES: Use awards to give credit and raise awareness in teams

Executive director of research, innovation and partnerships at the Namibia University of Science and Technology in Windhoek.

Research offices are a fairly recent development in Namibia. My team and I handle research analytics, monitor our university’s rankings and statistics, manage grants and support postgraduate students. On the innovation side, we work with industry partners, manage technology transfer and help to turn student ideas into commercial opportunities.

The function of research administrators is often misunderstood. People who have worked at the university for longer than we have will ask us, “What is your role again?” To earn recognition, you have to raise awareness and demonstrate your value every day. It helps to have an institution that is supportive of your role.

It’s particularly challenging to raise awareness about the services provided by support-staff members who work outside my office, which is the central research-administration hub of the university. That is why, starting in November, my university will give out awards specifically targeting these workers. These will be presented alongside the usual ‘researcher of the year’ prizes and the research-administration recognition awards that my office has handed out since 2022, and will recognize examples of good research support, including data collection and grant administration. Researchers will nominate support-staff members for the prize, and the winners will receive a small sum of money as well as extra opportunities for training and advancement. For instance, they could be supported in applying for accreditation from the International Professional Recognition Council (IPRC), based in Pretoria, which aims to advance and promote the research-management profession across Africa.

My university has also implemented a research-administration career track, similar to the academic career track, that includes the three levels of certification recognized by the IPRC: research-administration professional, research-management professional and senior research-management professional. The idea is to show that support services are an integral part of research, and to encourage people in these roles to see their career as one in which they can grow.

REBECCA KARTZINEL: Track value beyond individuals to secure their future

Director of the Brown University Herbarium in Providence, Rhode Island.

My job is to ensure that the daily operations of the herbarium run smoothly. I get help from our dedicated staff members, who handle everything from mounting and filing specimens to conducting archival research. They have exceptional skills, yet their work often goes unrecognized.

“Just get the admin to do it.” Why research managers are feeling misunderstood

My colleagues and I don’t seek a lot of external recognition, but we do want the herbarium to be used. The more activity in the herbarium, the more value the institution will see in it, and that in turn will make those of us who work there feel supported.

Scientists often access the herbarium for their research. However, lately, there’s been an increase in non-scientific use. We have undergraduates studying everything from landscape architecture to visual arts who are fascinated by the collections, which stretch back more than 100 years and have connections to the trade in enslaved people and the displacement of Indigenous people from the local area. Many people are studying these links to confront and learn from this difficult history.

Whenever possible, we try to ensure that visitors can see the herbarium’s staff at work. There’s usually a lot of interest in that. People like to watch old things being cared for properly, such as mending areas of 150-year-old specimens where the glue has failed.

Demonstrating the value of the herbarium is particularly important, because natural-history collections, such as herbaria, face an uncertain future. With the increasing shift to digitized knowledge, some people might feel that physical seed and plant specimens are not needed anymore. So, I’m tracking usage of the herbarium, to highlight its importance to science and society.

One long-term goal I have to raise the herbarium’s profile is to integrate it into state-level conservation planning, to help to cement its value beyond its use by researchers.