Abstract

Many higher education institutions around the world are engaged in efforts to tackle climate change. This takes place by not only reducing their own carbon footprint but also by educating future leaders and contributing valuable research and expertise to the global effort to combat climate change. However, there is a need for studies that identify the nature of their engagement on the topic, and the extent to which they are contributing towards addressing the many problems associated with climate change. Against this background, this paper describes a study that consisted of a review of the literature and the use of case studies, which outline the importance of university engagement in climate change and describe its main features. The study identified the fact that even though climate change is a matter of great relevance to universities, its coverage in university programmes is not as wide as one could expect. Based on the findings, the paper also lists the challenges associated with the inclusion of climate change in university programmes. Finally, it describes some of the measures which may be deployed in order to maximise the contribution of higher education towards handling the challenges associated with a changing climate.

Introduction

Many universities worldwide are continuously showing their commitment to preparing students for a role in society where they can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation1. Education plays an important role in changing people’s behaviour and attitudes; young people in the classrooms can learn about the impacts of climate change and how to mitigate and adapt to it, and they can be motivated to act2. The university’s role in relation to climate change education is critical in addressing scientific, environmental, social, and political challenges. Future decision-makers need to make their decisions from an informed position, and for this reason, climate change education and research programmes are of major importance3. Higher education institutions (HEIs) are part of both the solution and the problem regarding climate change4. By becoming actively engaged in efforts against climate change, HEIs can provide research-based and educational solutions to identify the most critical climate impacts and ways to handle them. Institutions can operate as hubs by creating, testing, and disseminating information about climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. Furthermore, HEI often undertakes research activities and seize upon opportunities to generate innovative knowledge that can help their local communities to adapt to climate change5. They deliver significant engagement and provide a platform for designing, testing and implementing innovative practices which may help in efforts to address the many impacts of climate change, locally, nationally, and globally. For instance, universities are among the key players in exploring and developing effective carbon pricing solutions including their economic feasibility and stimulating investments to reduce the technologies’ costs6. In the light of additional pressure posed by climate change on healthcare systems worldwide, it is essential to strengthen educational and training programs by introducing ‘climate change’ into medical school curricula and students’ activities. This will ensure that graduate health professionals acquire knowledge and skills to diagnose and respond to the health threats and impacts of climate change and understand public health issues7,8. Another role universities play in affecting climate action-related transformational change is through their engagement in advocacy and activism9. For instance, in the United States and Canada HEI have been involved in the fossil fuel divestment (FFD)10,11. In the United States, campaigns, primarily led by students, focus on justice including social, environmental, and economic issues10. In Canada, the campaigns use the signing of sit-ins, petitions, protests and rallies as well as branding and messaging from international environmental organizations11.

On the other hand, universities are contributors to climate change and hence, often feel an obligation to address individual impacts by greening their campuses. Many HEIs around the world have adopted initiatives such as the ‘carbon neutral university’ converting to low-emission or carbon–neutral organisations. As examples of these initiatives, the University for Sustainable Development in Eberswalde and Leuphana University both in Germany, are on a path to becoming carbon–neutral12. Others are engaging in initiatives to handle climate change as part of their efforts in the field of sustainable development13. In addition to carbon neutrality and waste management, universities aim to improve materials and resource use efficiency, environmental quality, retrofitting residential and non-residential construction buildings, and increase green areas and use of green transportation. For instance, Arizona State University, one of the largest public universities in the USA, with almost 100,000 students and employees, reported the achievement of carbon neutrality in 201914. Development of green campuses in China focuses on energy and resource efficiency through introducing energy-saving technology in campus buildings and facilities, energy statistics and auditing, as well as energy-saving operations. All these initiatives are strongly supported by the national government through policies and financial tools15. In Italy, the largest campus in the country of the University of Calabria (UNICAL) has significantly improved its energy systems through the use of photovoltaic, solar, and geothermal energy produced on campus16. Additionally, by introducing internal carbon pricing, universities could demonstrate practical implications for emission reduction through waste management17 and energy use18. Climate change education and approaches to greening campuses are also considered among the university’s strategies to contribute to sustainable development19. The strong linkage between these fields contributes to overcoming challenges in attaining the goals of the other. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 13, particularly Target 13.3, aims at “improving education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction, and early warning”. Furthermore, the wide range of initiatives launched to foster climate change literacy and education including the UNESCO Climate Change Education for Sustainable Development Programme20. The program contributed to advancing such topics as sustainable development and climate change in national curricula and educational standards across the countries21.

Most of the current studies report on one or several aspects concerning HEIs efforts to tackle climate change, like the aforementioned examples. Therefore, there is a need for studies that identify the overall nature of HEIs participation, and the extent to which they are contributing towards addressing the many problems associated with climate change. This paper explores universities’ engagement in addressing the threats posed by climate change, its main features, potential measures towards its maximisation, and associated challenges worldwide. To achieve this goal, this research consisted of a review of the literature and the use of case studies, which outline the importance of university engagement in climate change and describe its main features. The consequent sections describe methods used, obtained results, and lessons learned. The paper concludes by summarising the main findings and describing measures that higher education institutions should deploy in the long term, to better address climate change.

Methods

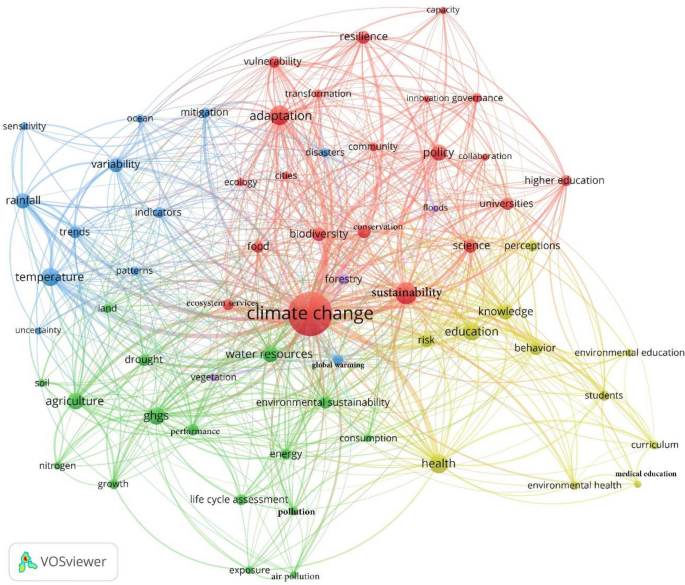

The objective of this study is to find out what climate change-related themes and topics have been pursued by universities. One way to answer this question is to examine publications that have focused on issues related to climate change education and research programs and initiatives in academic institutions. For this purpose, we relied on bibliometric analysis techniques as they can highlight key terms that have been used in the literature and their interactions. Various software tools such as CiteSpace, SciMAT, and VOSviewer are available for bibliometric analysis. Here, we used the latter as its term co-occurrence maps are more detailed and easier to interpret22,23. The input data for bibliometric analysis can be obtained from academic literature databases such as Scopus and the Web of Science. In this study, we used the Web of Science for its reputation to index quality peer-reviewed literature. To retrieve relevant literature for inclusion in the analysis, we developed a search string that is a combination of terms related to climate change, impacts of climate change, teaching and research programs, and academic institutions.

The full search string is available in the “Appendix”. It was created to embrace the main topics related to this research (inclusion criteria), with a structure of four main blocks. The first is related to terms related to climate change and encompasses variations commonly used in the literature such as ‘global warming’, ‘climate variability’, etc. The second block of terms is related to ‘extreme events’, while the third brings some practices of universities such as education, teaching, training, curricula, research, etc. Finally, the last section of the search string was created due to the focus selected in this study, which is to understand the perspective of higher education institutions. It is worth considering, however, that the terms chosen might now encompass the totality of possible terms related to climate change since there is a huge variety used throughout the literature. The authors are aware of this issue and brought this discussion as a limitation in the conclusions section.

The initial literature search was conducted on July 18, 2022, and returned 1214 documents. These documents were screened to only include those that show how climate change education and/or research is pursued by universities (exclusion criteria). At the end of the screening process. A total of 794 documents remained in the database and were used for term co-occurrence analysis in VOSviewer. The co-occurrence analysis was done in several steps to ensure obtaining the most accurate outputs. To be more specific, after the initial analysis, we found out many synonyms need to be merged (e.g., ‘climate change’ and ‘climate-change’). For this purpose, we developed a thesaurus file and added it to the software. The process was repeated until no synonyms were found in the output. The final output (Fig. 1) is a network of nodes and links, where node size is proportional to the occurrence to frequency (of terms) and link width is proportional to the strength of connections between terms. Closely connected terms form clusters that can be interpreted as major thematic areas that have received relatively more attention in the literature. In this perspective, it was possible to label clusters manually since the number of clusters formed and the terms extracted were manageable. To label the clusters, the authors analysed the relationship of terms of a specific cluster and provided a label representing the discussion embedded in each one of the clusters24. These will be further explained in the results section.

Results of the term co-occurrence analysis.

In addition to this, we completed the literature review by selecting a set of key case studies regarding four core areas for university engagement, namely (1) research and development, (2) teaching and learning, (3) governance and operations, and (4) civic engagement and community outreach. We performed a literature mapping using the Web of Science database to identify the case studies. This was completed using a general search using Google and recognised case studies implemented by universities in different countries. Relevant case studies were selected by the research team using the following criteria: number of citations, degree of innovation, diversity of knowledge and research areas, geographical diversity, and potential for replication and mainstreaming in other contexts. Four tables were designed with selected examples, which entail a specific set of information, namely the type of climate change work undertaken, the main purpose of the implemented initiative, the name of the participating universities, and the country. Also, to ensure the tracing of the information, the tables contain bibliographical references or web links. This also allows a cross-check of the information and enables readers to obtain further details.

Using this literature mapping approach identified, collected, and analysed the existing literature on specific case studies of interest. This process made it possible to highlight and synthesise key issues from the selected literature, thus providing clear insights into the state of knowledge on key case study topics. Accordingly, literature mapping conceptualised a range of possible future research directions, policy implications, and/or practical recommendations for different stakeholder groups. Crucially, surveying the state of the art in this manner helped the researchers to avoid duplicating previous work, identify areas where further investigation is needed, and enable the development of strategies for evidence-based decision-making that researchers, policymakers, and practitioners may leverage in different contexts.

Results and discussion

Bibliometric assessment

Figure 1 shows that multiple topics related to climate change adaptation and mitigation have been addressed in the context of higher education. This is evidenced by the diversity of terms in each of the four clusters which can be considered as research strands explored by the literature in the field. The output of the term co-occurrence analysis (Fig. 1) shows that multiple topics related to climate change adaptation and mitigation have been addressed in publications on climate change-related education and/or research activities/programs.

The red cluster describes aspects related to general policies aimed at reducing vulnerabilities and enhancing resilience and adaptive capacity, embracing terms related to biodiversity, food systems, and ecosystem services. Studies in this cluster usually discuss the relevance of governance in HEIs to ensure universities’ contribution towards reducing their impact, implementing adaptation strategies on climate change vulnerabilities, and fostering sustainable development25,26,27. This governance perspective is relevant since it could contribute to the universities’ process of ensuring that desired practices are initiated, implemented, and continued by the several stakeholders engaged in the process28. This perspective also implies the adaptation policies that aim to assist the universities in assembling their several systems, tackling the university’s campus operations, and helping society by producing research on the climate change field, especially related to themes such as ecology, food, and biodiversity. Ecology and biodiversity policies in the context of higher institutions are also discussed, especially in the context of green spaces, generating externalities in the perspective of ecological function and urban communities29 and fostering the discussion of how to maintain biodiversity in a context of climate change adaptation since many species are constrained by changes in climate30,31. This cluster also presents studies on campus as ecosystems, exploring whether humans and the biosphere could be reconnected, enhancing the awareness of how to deal with the biodiversity loss related to climate change32.

The yellow cluster is focused on climate and environmental education and risk reduction. This cluster, in particular, focuses on the educational practices of universities and the extent to which they address climate change and environmental challenges33,34,35,36. More specifically, it deals with the knowledge and sustainability behaviour of students in the process of educating well-versed agents in climate change aspects and capable of conducting adaptation and mitigation strategies37,38. This cluster also reports on integrating disaster reduction for extreme events39,40,41, highlighting the significance of disaster risk education and environmental awareness programs to effectively address these challenges42.

Studies that belong to the blue cluster, in turn, are mainly focused on assessing the temperature, precipitation, and other aspects of climate change variability43,44,45. The relation this cluster has with HEIs is mainly focused on research practices, where research centres contribute to assessing climate change challenges by finding patterns and estimating indicators related, for example, to rainfall, temperature, and extreme events46,47. For example, Stefanidis and Alexandridis48 studied the temporal variability, precipitation trends, and evapotranspiration in two forest regions in Greece. They discussed the drought scenarios and the implications for climate change adaptation. Similarly, Rawat and colleagues49 analysed the rainfall variability and intensity of long-term monthly rainfall data using the Precipitation Concentration Index, which, according to the authors, could prepare governments for extreme weather events, which are imperative to adaptation to climate change conditions.

Finally, the green cluster is the second in a number of terms and has two main discussion streams. The first one is related to the climate change impact on water resources, land, and soil degradation, and inducing droughts50,51,52,53,54,55. The second perspective this cluster highlights is related to the precedents of climate change as well as the adaptation and mitigation strategies to address the challenges related to climate change. For example, there are reports on the potential of organic agricultural systems instead of crop productions using nitrogen-based fertilisers, since it leads to reduced N2O emissions56,57,58,59,60, the importance of renewable energy production systems60,61 as well as the industrial and human activities which can contribute to the emission of GHGs and environmental pollution62, impacting negatively human health63,64.

Cases

Research and development

Climate change research has been led since 1896 with Svante Arrhenius founding paper65. Since then, the volume of scientific literature on climate change has been increasing rapidly. The total number of articles on climate change exceeds 120 000 up to 201566; almost 90 000 papers were published between 1991 and 201167. New fields of research have merged over time, often responding to society’s needs, such as attribution science, first documented in 200468 and included in the IPCC AR569, the study of social health impacts of climate change, the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous perspectives, and generally speaking a growing emphasis on adaptation, including novel approaches like community-based adaptation70 and participatory action-research71,72,73,74. Table 1 presents a set of elected case studies on research institutions.

At the same time, climate change research has become more interdisciplinary and transitioned from individual researchers to research centres, hosted by one or several institutions. It also more often than before involves stakeholders from society, leading to collaborative research initiatives. We illustrate this through examples for all three types of research centres in Canada: single-university—the Prairie Climate Centre, multi-university—the Réseau Inondations InterSectoriel du Québec (RIISQ), collaborative, and Ouranos. Two of the most influential research centers, both in numbers and impact of publications, are the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, which pioneered ground-breaking work on planetary boundaries, climate tipping points, and exploration of past and future climates in an interdisciplinary perspective75,76,77,78. It must be stressed that climate change research is not an exclusivity of European or North American universities. Institutions like the Munasinghe Institute for Development and the International Centre for Climate Change and Development are highly respected in the fields of adaptation or sustainability applied to climate change and incorporate issues, approaches, and values relevant to the Global South in their research. As we wish to demonstrate through the selected research projects below, there is a trend for the development of international, interdisciplinary cross-institution initiatives in climate change research, certainly also favoured by funding agency policies, especially in the research and development sector. Such projects can have a real impact on the ground; however, they need careful scientific and organisational planning in order to be truly successful79. Table 2 presents a set of elected case studies on research projects.

Teaching and learning

Equipping graduates with the necessary skills and capabilities required to succeed in both their personal and professional lives is a crucial goal for higher education institutions. In higher education institutions, there are varied interpretations of the cultural, social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainable development. Simultaneously, teachers do not reach a consensus on how these different dimensions are interconnected80. Furthermore, there are diverse perspectives on how these matters should be approached within various degree programs and courses, and this can influence students’ perceptions of values related to sustainability, ethics, and social responsibility81. However, understanding the complexity of climate change may be challenging for students and educators82. This could clarify why students’ awareness of sustainability issues is not uniform or consistent83. However, it also underscores the potential intricacy associated with enhancing awareness of social, economic, and environmental issues among students84. From this viewpoint, students should acquire the skills not just to translate innovative ideas into tangible projects but also to effectively integrate environmental, social, and financial goals85.

In this regard, it is vital to increase their interest in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as prepare graduates to implement real-life solutions based on sustainability criteria86. Against this background, it is necessary not only to identify misconceptions and guarantee a proper understanding of climate change’s roots and consequences but also to help students become active and critical citizens capable of facilitating real change. In this context, the integration of SDGs in higher education requires the identification and clarification of educational objectives, as well as the adoption of innovative teaching and learning strategies suitable to transform education87.

Table 3 presents a set of selected case studies on teaching and learning. Several studies have addressed the issue of students’ perceptions and misconceptions regarding climate change. Some studies have used large samples to explore the drivers of pro-environmental behaviour88, but small-group, classroom-based, or program-based studies are also frequent approaches to explore the different ways how students understand climate change89,90,91. As mentioned below, defining, and clarifying the required capabilities and the necessary skills to accelerate the implementation of the SDGs in higher education is essential92. A growing number of studies have addressed this issue, using different strategies such as comprehensive approaches based on literature review techniques and the use of surveys87, as well as small-group studies relying on quantitative and qualitative techniques93. In addition to this, non-conventional, student-centered teaching and learning techniques are becoming increasingly popular in higher education due to their potential to help students acquire multiple learning outcomes94. Methodologies such as problem-based learning95,96,97, inquiry-based learning98, gamification99,100, or participatory case studies101, are examples of innovative strategies to promote education for sustainable development.

Governance, operations, and institutional practice

All around the world, universities are increasingly adopting carbon–neutral goals and practices102,103. This is reflected by the growing number of higher education providers that are aiming to become fully carbon–neutral institutions (through low-carbon operational practices) while at the same time innovating their curricula to better educate students (about the benefits of carbon neutrality)1,12,104. With this twin strategy, universities are decreasing their own “carbon footprint” (by lowering institution-linked greenhouse gasses) and increasing the wider community’s “carbon brain print” (by teaching about low-carbon living)102,105. The literature, therefore, categorises “governance” into matters about the immediate institutional governance and operational practices (of the universities themselves) and their secondary flow-on function of informing and influencing the governance and operational practices of other key stakeholders beyond their organisational confines (e.g., local communities, national governments, and the corporate sector)106. Table 3 shows a set of selected case studies addressing areas of governance, operations, and institutional practice. In terms of facilitating institution-wide carbon neutrality, universities are implementing a raft of strategies that may include private-private solar system partnerships102, renewables, electric vehicles, tree plantation and enhanced energy efficiency107, remote sensing, and campus tree surveys to maximise biosequestration and campus-based ecosystem services108, campus community gardening to enhance CSR and institutional sustainability practice109, in addition to a range of other priority actions that may achieve net zero carbon buildings and (Paris-aligned) carbon reduction targets102,110. Furthermore, many universities have announced institutional commitments to divest their endowments from fossil fuel holdings while recalibrating their operational practices in alignment with the UN SDGs111,112,113. These actions may have image-enhancing effects114. Pertinent performance metrics are captured by the Times Higher Education (THE) Impact Rankings, an annual process that assesses universities against the UN SDGs. In its most recent fourth edition, THE has ranked a total of 1406 universities from 106 countries/regions115. Finally, additional information on the strategies, operations, and budgetary plans of higher education institutions (HEIs) regarding their transition to net zero or carbon neutrality might not be found in academic publications but could be available in “grey literature” produced by the HEIs themselves, focusing on their performance and strategic vision. Table 4 includes a set of selected case studies on governance, operations, and institutional practice.

Civic engagement and community outreach

The crucial role that Universities must play is also reflected by the increasing efforts from higher education institutions to foster civic engagement and expand their community outreach. Universities play a vital role in fostering civic commitment and community outreach within their localities. By leveraging their resources, expertise, and diverse talent pool, universities can initiate impactful initiatives that address community needs and promote positive social change. One effective approach is to establish university-community partnerships, where faculty, students, and staff collaborate with local organizations and residents to identify pressing issues and co-create sustainable solutions. Additionally, universities can integrate service-learning programs into their curricula, encouraging students to actively engage with the community while applying their academic knowledge to real-world challenges. Offering workshops, seminars, and public events on relevant topics further encourages dialogue and knowledge-sharing between the institution and the community. By actively involving themselves in the community’s fabric, universities can contribute to the betterment of society, nurture socially responsible citizens, and empower students to become agents of positive transformation.

In this context, cooperation among stakeholders led to the concept of “co-creation for sustainability”, which deals with relevant notions and innovative strategies for transformative research116, such as participatory action research (PAR) and other community-based research strategies, the creation of urban living labs, and the use of innovative strategies for civic cooperation such as student service learning117. Table 5 shows a set of selected successful case studies where cooperation between universities and local stakeholders proved to contribute to facilitating civic engagement/community outreach in their local communities. Against this background, PAR, a community-based technique in which beneficiaries take an active role in research118, could be used for multiple purposes to deal with the challenges generated by climate change, such as improving climate planning processes119, increase engagement of different stakeholders and identify the scope for developing the adaptive capability of local communities120, monitor environmental risks and damage121, or strengthening climate justice122. Other forms of transformative research rely on multidisciplinary teams formed by diverse stakeholders engaged in evaluating knowledge and providing technical advice123 or fostering private–public partnerships to boost engineering solutions124, among other examples. In line with this multi-stakeholder cooperation, universities and other higher education institutions play a crucial role in creating ‘urban living labs’, understood as spaces where research is used for promoting innovation and collaboration to tackle social, economic, and environmental needs125,126,127. Finally, experiential learning strategies such as student service learning are becoming increasingly popular in higher education128, mainly because of their potential to foster critical thinking as well as promote social and civic engagement among students and enhance cooperation between different social actors125, 129.

Conclusions

As this paper has outlined, universities can provide substantial contributions to both consumption and emissions globally. They also have the potential to play a key role in efforts to drive sustainability, both locally and globally.

As this paper has shown, many universities are switching to green operations that involve sustainability in campus activities such as water and energy consumption, waste production, and personal and institutional mobility, all of which have connections with climate change. Improvements may be pursued in respect of the implementation of activities such as smart waste management, sustainable transportation systems, and the more sustainable maintenance of existing buildings. Since daily campus operations result in the usage of large amounts of energy, it is important that higher education institutions that currently use fossil-fuel-based energy -which results in greater greenhouse gas releases- switch towards renewable energy use.

The production of waste also contributes greatly to global carbon emissions, and universities produce a significant amount of waste. Therefore, it is important to put in place appropriate strategies to manage waste and ideally prevent it, especially food waste since a large percentage of food wastage is generated at university canteens. There are ample examples of successfully-run recycling programmes, which may mobilise staff and students in a meaningful way. Some may not only reuse waste but also produce energy from it. Moreover, a further promising area is the use of cleaner transportation methods, as a tool to reduce the carbon footprint of higher education institutions. This may involve the use of campuswide shuttle services, carpooling, or the use of bicycles, by both staff and students. There is also much scope to reduce greenhouse emissions from travel. Whereas this is an essential part of universities´ operations -since both staff and students regularly use travel as part of their mobility and to attend conferences. Here, adequate solutions are also needed, for instance, the optimisation of trips and routes, and greater use of online facilities for those events whose physical attendance is not essential.

Higher education institutions can take several steps to address climate change. Such steps range from curriculum reform to creating new research initiatives and collaborations. Some of the recommendations that may further the cause of a greater engagement of universities on climate change include:

-

1.

Curriculum Reform: as it is shown in Table 3, there are few studies focusing on climate change aspects in curriculums, indicating a large opportunity for research. In this sense, higher education institutions should review their curricula to ensure that current and future generations of students are educated in the fundamentals of climate science (in technical subjects) and the global effects of climate change (in non-technical ones).

-

2.

Education & Awareness: Aligned with the first recommendation, institutions should promote educational campaigns and public awareness initiatives to educate students and the public on the importance of reducing their carbon footprint. The case studies on civic engagement and community outreach shown in Table 5 evidence interesting examples of ways of implementing this kind of initiative for the public in general. As presented in the literature, the complexity and inter-transdisciplinary character of sustainability inhibits its understanding to some extent, but concrete examples of carbon footprint reduction can be an important approach to address this challenge.

-

3.

Research: There are relevant challenges highlighted in the literature for inserting climate change in university programmes, evidencing the need for studies to deeply analyse these difficulties and propose manners for overcoming them. In addition, the existing research institutions, initiatives, and/or programs focusing on climate change-related aspects (Tables 1 and 4) can play a key role in enhancing the efforts in the field and institutions worldwide should encourage and fund research initiatives that seek to understand the causes and effects of climate change, develop solutions and technologies, and identify innovative strategies for addressing the climate crisis.

-

4.

Collaboration: In the same line of reasoning of the previous recommendation, institutions should establish and enhance partnerships with local governments, non-profit organizations, and other stakeholders to collaborate on initiatives to mitigate climate change.

-

5.

Renewable Energy: Another evidenced source of improvement opportunity regarding climate change is that institutions should invest in renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and geothermal, to reduce their emissions and promote sustainability. They should, in other words, practice what they preach.

-

6.

Green Buildings: Aligned with the previous recommendation, institutions should strive to create and maintain sustainable buildings, such as LEED-certified buildings, to reduce their environmental impact. In Table 4, examples of case studies on governance, operations, and institutional practice are evidenced, which can be used as a starting point for further development.

This paper has some limitations. The first is related to the sample. The study analysed 1214 documents that only considered how climate change education and/or research is pursued by universities, without focusing on other parameters. Secondly, only 794 documents remained in the database and were used for term co-occurrence analysis in VOSviewer. In addition, the case studies focused on four areas, namely research and development, teaching and learning, governance and operations, and civic engagement and community outreach, and did not consider elements such as collaboration with external organisations. Finally, the authors used the main terms to create the search string, and because of the diversity of the field, it was not possible to track all the possible terms related to each one of the four dimensions. However, this last limitation could be an opportunity for future studies as new terms that are not commonly used till the date of this research might start to gain attention and start to be adopted. Despite these limitations, the paper provides a welcome addition to the literature since it documents and promotes the current emphasis given by universities to climate change.

As to future trends on climate change and universities, there is a perceived need for greater engagement. Universities are important hubs of innovation and knowledge creation, with a comprehensive body of information and experience, which can significantly help to address the challenges of climate change, and across several subjects and contexts. As such, more universities are expected to intensify their efforts in research, education, and outreach activities related to climate change.

Moreover, universities should become more involved in the public policy and advocacy sphere, advocating for solutions to climate change and engaging in climate-related projects. This involvement is expected to increase as universities become more involved in the global climate change discourse.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

-

Cordero, E. C., Centeno, D. & Todd, A. M. The role of climate change education on individual lifetime carbon emissions. PLoS ONE 15, e0206266–e0206266 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

UNESCO. Climate change education (2022).

-

Molthan-Hill, P., Worsfold, N., Nagy, G. J., Leal Filho, W. & Mifsud, M. Climate change education for universities: A conceptual framework from an international study. J. Clean. Prod. 226, 1092–1101 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Washington-Ottombre, C., Brylinsky, S. E., Carlberg, D. B. & Weisbord, D. Climate resilience planning and organizational learning on campuses and beyond: A comparative study of three higher education institutions. Univ. Initiat. Clim. Change Mitig. Adapt. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89590-1_5/COVER (2018).

Google Scholar

-

American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. Higher Education’s Role in Adapting to a Changing Climate (2012).

-

Barron, A. R., Parker, B. J., Sayre, S. S., Weber, S. S. & Weisbord, D. J. Carbon pricing approaches for climate decisions in U.S. higher education: Proxy carbon prices for deep decarbonization. Elementa: Sci. Anthr. 8, 42 (2020).

-

Goshua, A. et al. Addressing climate change and its effects on human health: A call to action for medical schools. Acad. Med.: J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 96, 324–328 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wellbery, C. et al. It’s time for medical schools to introduce climate change into their curricula. Acad. Med.: J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 93, 1774–1777 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Gardner, C. J., Thierry, A., Rowlandson, W. & Steinberger, J. K. From publications to public actions: The role of universities in facilitating academic advocacy and activism in the climate and ecological emergency. Front. Sustain. 2, 42 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Gibson, D. & Duram, L. A. Shifting discourse on climate and sustainability: Key characteristics of the higher education fossil fuel divestment movement. Sustainability 12, 10069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310069 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Maina, N. M., Murray, J. & McKenzie, M. Climate change and the fossil fuel divestment movement in Canadian higher education: The mobilities of actions, actors, and tactics. J. Clean. Prod. 253, 119874 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Udas, E., Wölk, M. & Wilmking, M. The “carbon-neutral university”—a study from Germany. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 19, 130–145 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Mccowan, T., Leal Filho, W. & Brandli, L. Universities facing climate change and sustainability (2021).

-

University, A. S. Achieving Carbon Neutrality at Arizona State University (2020).

-

Tan, H., Chen, S., Shi, Q. & Wang, L. Development of green campus in China. J. Clean. Prod. 64, 646–653 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

European Commission. Project Green Campus: Studying in green surroundings! Additional tools. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2021/07/07-07-2021-project-green-campus-studying-in-green-surroundings (2021).

-

Lee, S. & Lee, S. University leadership in climate mitigation: reducing emissions from waste through carbon pricing. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 23, 587–603 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gillingham, K., Carattini, S. & Esty, D. Lessons from first campus carbon-pricing scheme. Nature 551, 27–29 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Kelly, O. et al. Education in a warming world: Trends, opportunities and pitfalls for institutes of higher education. Front. Sustain. 3, 920375 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

UNESCO. Education for sustainable development: Partners in action; halfway through the global action programme on education for sustainable development (2017).

-

Reimers, F. M. The role of universities building an ecosystem of climate change education. Int. Explor. Outdoor Environ. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57927-2_1/TABLES/3 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Sharifi, A. Co-benefits and synergies between urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141642 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Mugabushaka, A. M., Van Eck, N. J. & Waltman, L. Funding COVID-19 research: Insights from an exploratory analysis using open data infrastructures. Quant. Sci. Stud. 3, 560–582 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Eustachio, J. H. P. P., Caldana, A. C. F. & Leal Filho, W. Sustainability leadership: Conceptual foundations and research landscape. J. Clean. Prod. 415, 137761 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Franco, I. et al. Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustain. Sci. 14, 1621–1642 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Oliveira, A. L. K. S. de. O profissional de sustentabilidade nas organizações: Uma análise das suas trajetórias e narrativas de aprendizagem experiencial (2018).

-

Owen, R., Fisher, E. & McKenzie, K. Beyond reduction: Climate change adaptation planning for universities and colleges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 14, 146–159 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Mader, C., Scott, G. & Abdul Razak, D. Effective change management, governance and policy for sustainability transformation in higher education. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 4, 264–284 (2013).

-

Susilowati, A. et al. Maintaining tree biodiversity in urban communities on the university campus. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers. 22, 2839–2847 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, J. et al. University campuses as valuable resources for urban biodiversity research and conservation. Urban For. Urban Green. 64, 127255 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, J., Yu, M., Tomlinson, K. & Slik, J. W. F. Patterns and drivers of plant biodiversity in Chinese university campuses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 164, 64–70 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Colding, J. & Barthel, S. The role of university campuses in reconnecting humans to the biosphere. Sustainability 9, 2349 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W. & Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 241, 108224 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

McKenzie, M. Climate change education and communication in global review: Tracking progress through national submissions to the UNFCCC Secretariat. Environ. Educ. Res. 27, 631–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1903838 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A. & Chaves, W. A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 791–812 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Jorgenson, S. N., Stephens, J. C. & White, B. Environmental education in transition: A critical review of recent research on climate change and energy education. J. Environ. Educ. 50, 160–171 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Al-Naqbi, A. K. & Alshannag, Q. The status of education for sustainable development and sustainability knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of UAE University students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 19, 566–588 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Anderson, A. Climate change education for mitigation and adaptation. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 6, 191–206 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Ludy, J. & Kondolf, G. M. Flood risk perception in lands ‘protected’ by 100-year levees. Nat. Hazards 61, 829–842 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Rahma, A., Mardiatno, D. & Hizbaron, D. R. Developing a theoretical framework: school ecosystem-based disaster risk education. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2023.2214041 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Vehola, A., Malkamäki, A., Kosenius, A. K., Hurmekoski, E. & Toppinen, A. Risk perception and political leaning explain the preferences of non-industrial private landowners for alternative climate change mitigation strategies in Finnish forests. Environ. Sci. Policy 137, 228–238 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Birkmann, J. & von Teichman, K. Integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: Key challenges-scales, knowledge, and norms. Sustain. Sci. 5, 171–184 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Grimm, A. M. Interannual climate variability in South America: Impacts on seasonal precipitation, extreme events, and possible effects of climate change. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 25, 537–554 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Kenyon, J. & Hegerl, G. C. Influence of modes of climate variability on global temperature extremes. J. Clim. 21, 3872–3889 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Sarkisyan, A. S. & Sündermann, J. E. Modelling Ocean Climate Variability 1–374 (Springer, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9208-4/COVER.

Google Scholar

-

Funk, C. et al. A high-resolution 1983–2016 Tmax climate data record based on infrared temperatures and stations by the climate hazard center. J. Clim. 32, 5639–5658 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Wulfmeyer, V. & Henning-Müller, I. The climate station of the University of Hohenheim: Analyses of air temperature and precipitation time series since 1878. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 113–138 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Stefanidis, S. & Alexandridis, V. Precipitation and potential evapotranspiration temporal variability and their relationship in two forest ecosystems in Greece. Hydrology 8, 160 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Rawat, K. S., Pal, R. K. & Singh, S. K. Rainfall variability analysis using Precipitation Concentration Index: A case study of the western agro-climatic zone of Punjab, India. Indones. J. Geogr. 53, 373–387 (2021).

-

Al-Kalbani, M. S., Price, M. F., Abahussain, A., Ahmed, M. & O’Higgins, T. Vulnerability assessment of environmental and climate change impacts on water resources in Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Sultanate of Oman. Water 6, 3118–3135 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Asadi Zarch, M. A., Sivakumar, B. & Sharma, A. Droughts in a warming climate: A global assessment of Standardized precipitation index (SPI) and Reconnaissance drought index (RDI). J. Hydrol. 526, 183–195 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Beniston, M. & Stoffel, M. Assessing the impacts of climatic change on mountain water resources. Sci. Total Environ. 493, 1129–1137 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Buragiene, S. et al. Experimental analysis of CO2 emissions from agricultural soils subjected to five different tillage systems in Lithuania. Sci. Total Environ. 514, 1–9 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Docherty, K. M. et al. Key edaphic properties largely explain temporal and geographic variation in soil microbial communities across four biomes. PLOS ONE 10, e0135352 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Kasei, R., Diekkrüger, B. & Leemhuis, C. Drought frequency in the Volta Basin of West Africa. Sustain. Sci. 5, 89–97 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Boateng, K. K., Obeng, G. Y. & Mensah, E. Rice cultivation and greenhouse gas emissions: A review and conceptual framework with reference to Ghana. Agriculture 7, 7 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Chen, H., Hou, H., Cai, H. & Zhu, Y. Soil N2O emission characteristics of greenhouse tomato fields under aerated irrigation. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 32, 111–117 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Forkuor, G., Amponsah, W., Oteng-Darko, P. & Osei, G. Safeguarding food security through large-scale adoption of agricultural production technologies: The case of greenhouse farming in Ghana. Clean. Eng. Technol. 6, 100384 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Scialabba, N. E. H. & Miller-Lindenlauf, M. Organic agriculture and climate change. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 25, 158–169 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Perea-Moreno, M. A., Hernandez-Escobedo, Q. & Perea-Moreno, A. J. Renewable energy in urban areas: Worldwide research trends. Energies 11, 577 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Willsteed, E., Gill, A. B., Birchenough, S. N. R. & Jude, S. Assessing the cumulative environmental effects of marine renewable energy developments: Establishing common ground. Sci. Total Environ. 577, 19–32 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Barontini, F., Galletti, C., Nicolella, C. & Tognotti, L. GHG emissions in industrial activities: The role of technologies for their management and reduction. Agrochimica 27–37 (2019).

-

Berger, M., Bastl, M., Bouchal, J., Dirr, L. & Berger, U. The influence of air pollution on pollen allergy sufferers. Atemwegs- und Lungenkrankheiten 48, 49–53 (2022).

-

Stanek, L. W., Brown, J. S., Stanek, J., Gift, J. & Costa, D. L. Air pollution toxicology—A brief review of the role of the science in shaping the current understanding of air pollution health risks. Toxicol. Sci. 120, S8–S27 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Arrhenius, S. On the Influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground. Philos. Mag. 41, 237–276 (1896).

Google Scholar

-

McSweeney, R. The most ‘cited’ climate change papers – Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-the-most-cited-climate-change-papers/ (2015).

-

Lynas, M., Houlton, B. Z. & Perry, S. Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610–614 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Bindoff, N. L. et al. IPCC 2013 AR5 – Chapter 10: Detection and Attribution of Climate Change: from Global to Regional. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, (2013).

-

Reid, H. Ecosystem- and community-based adaptation: Learning from community-based natural resource management. Clim. Dev. 8, 4–9 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Chouinard, O., Plante, S., Weissenberger, S., Noblet, M. & Guillemot, J. The participative action research approach to climate change adaptation in Atlantic Canadian coastal communities. Clim. Change Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53742-9_5 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

German, L. A. et al. The application of participatory action research to climate change adaptation in Africa (2012).

-

Gonsalves, J. A new relevance and better prospects for wider uptake of social learning within CGIAR. CCAFS Working Paper (2013).

-

Plante, S., Vasseur, L. & Dacunha, C. Adaptation to climate change and participatory action research (PAR): Lessons from municipalities in Quebec, Canada. Clim. Adapt. Gov. Cities Reg.: Theor. Fundam. Pract. Evid. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118451694.ch4 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding 15 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Rahmstorf, S. Ocean circulation and climate during the past 120,000 years. Nature 419, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01090 (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Lenton, T. M. et al. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 1786–1793. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705414105 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Claussen, M. & Gayler, V. The greening of the Sahara during the mid-Holocene: Results of an interactive atmosphere-biome model. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. Lett. 6, 369–377 (1997).

Google Scholar

-

Cundill, G. et al. Large-scale transdisciplinary collaboration for adaptation research: Challenges and insights. Glob. Chall. 3, 1700132 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Rouhiainen, H. & Vuorisalo, T. Higher education teachers’ conceptions of sustainable development: Implications for interdisciplinary pluralistic teaching. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 1713–1730 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Delgado, C., Venkatesh, M., Castelo Branco, M. & Silva, T. Ethics, responsibility and sustainability orientation among economics and management masters’ students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21, 181–199 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Vladimirova, K. & Le Blanc, D. Exploring links between education and sustainable development goals through the lens of UN flagship reports. Sustain. Dev. 24, 254–271 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Kuthe, A. et al. How many young generations are there? – A typology of teenagers’ climate change awareness in Germany and Austria. J. Environ. Educ. 50, 172–182 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Kolleck, N. The emergence of a global innovation in education: Diffusing Education for Sustainable Development through social networks. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 1635–1653 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Marathe, G. M., Dutta, T. & Kundu, S. Is management education preparing future leaders for sustainable business?: Opening minds but not hearts. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21, 372–392 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Leal Filho, W. et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack?. J. Clean. Prod. 232, 285–294 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Leal Filho, W. et al. A framework for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in university programmes. J. Clean. Prod. 299, 126915 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Díaz, M. F. et al. Psychological factors influencing pro-environmental behavior in developing countries: Evidence from Colombian and Nicaraguan students. Front. Psychol. 11, 580730 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Pascua, L. & Chang, C. H. Using intervention-oriented evaluation to diagnose and correct students’ persistent climate change misconceptions: A Singapore case study. Eval. Progr. Plan. 52, 70–77 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Mahaffy, P. G. et al. Beyond ‘inert’ ideas to teaching general chemistry from rich contexts: Visualizing the chemistry of climate change (VC3). J. Chem. Educ. 94, 1027–1035 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Prasad, R. R. & Mkumbachi, R. L. University students’ perceptions of climate change: the case study of the University of the South Pacific-Fiji Islands. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 13, 416–434 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Leal Filho, W. Viewpoint: Accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21, 507–511 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Seo, E., Ryu, J. & Hwang, S. Building key competencies into an environmental education curriculum using a modified Delphi approach in South Korea. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 890–914 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Leal Filho, W. Non-conventional learning on sustainable development: Achieving the SDGs. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33, 1–4 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Weber, J. M., Lindenmeyer, C. P., Liò, P. & Lapkin, A. A. Teaching sustainability as complex systems approach: A sustainable development goals workshop. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 22, 25–41 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Sierra, J. & Suárez-Collado, Á. Understanding economic, social, and environmental sustainability challenges in the global south. Sustainability 13, 7201 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Sierra, J. & Suárez-Collado, Á. Wealth and power: Simulating global economic interactions in an online environment. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 20, 100629 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Pharo, E. J. et al. Can teacher collaboration overcome barriers to interdisciplinary learning in a disciplinary university? A case study using climate change. Teach. High. Educ. 17, 497–507 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Sierra, J. & Suárez-Collado, Á. Active learning to foster economic, social, and environmental sustainability awareness 95–110 (2023) doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22856-8_6/COVER.

-

Sierra, J. The potential of simulations for developing multiple learning outcomes: The student perspective. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 18, 100361 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Krütli, P., Pohl, C. & Stauffacher, M. Sustainability learning labs in small island developing states: A case study of the Seychelles. GAIA 27, 46–51 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Baumber, A., Luetz, J. M. & Metternicht, G. Carbon neutral education: Reducing carbon footprint and expanding carbon brainprint 1–13 (2019). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69902-8_13-1.

-

Chaplin, G., Dibaj, M. & Akrami, M. Decarbonising universities: Case study of the University of Exeter’s green strategy plans based on analysing its energy demand in 2012–2020. Sustainability 14, 4085 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Helmers, E., Chang, C. C. & Dauwels, J. Carbon footprinting of universities worldwide: Part I—objective comparison by standardized metrics. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33, 30 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Chatterton, J. et al. Carbon brainprint—An estimate of the intellectual contribution of research institutions to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 96, 74–81 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Leal Filho, W. et al. Handling climate change education at universities: An overview. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33, 1–19 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Mustafa, A., Kazmi, M., Khan, H. R., Qazi, S. A. & Lodi, S. H. Towards a carbon neutral and sustainable campus: Case study of NED university of engineering and technology. Sustainability 14, 794 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Tonietto, R. et al. Toward a carbon neutral campus: A scalable approach to estimate carbon storage and biosequestration, an example from University of Michigan. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 22, 1108–1124 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Luetz, J. M. & Beaumont, S. Community gardening: Integrating social responsibility and sustainability in a higher education setting—A case study from Australia. In Social Responsibility and Sustainability. World Sustainability Series (ed. Leal Filho, W.) 493–519 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03562-4_26.

-

Planning, U. B. C. C. & C. Climate Action Plan 2030, UBC Vancouver Climate Action Plan 2030. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada (2021).

-

Monaco, A. Divestment and greenhouse gas emissions: An event-study analysis of university fossil fuel divestment announcements. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2022.2030664 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bratman, E., Brunette, K., Shelly, D. C. & Nicholson, S. Justice is the goal: Divestment as climate change resistance. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 6, 677–690 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Chandler, D. L. Agreement on climate-related action reached by MIT administration and student-led group. MIT News Office https://news.mit.edu/2016/agreement-climate-related-action-reached-mit-administration-student-led-group-0303 (2016).

-

Salvioni, D. M., Franzoni, S. & Cassano, R. Sustainability in the higher education system: An opportunity to improve quality and image. Sustainability 9, 914 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Education, T. H. Impact rankings 2022. Preprint at (2022).

-

Mertens, D. M. Transformative research methods to increase social impact for vulnerable groups and cultural minorities. Int. J. Qual. Methods 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211051563 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Bogedain, A. & Hamm, R. Strengthening local economy—an example of higher education institutions’ engagement in “co-creation for sustainability”. Region 7, 9–27 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Buckles, D. J. Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry 1–474 (Routledge, 2013). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203107386.

Google Scholar

-

Trundle, A., Barth, B. & Mcevoy, D. Leveraging endogenous climate resilience: Urban adaptation in Pacific Small Island Developing States. Environ. Urban. 31, 53–74 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Mapfumo, P., Adjei-Nsiah, S., Mtambanengwe, F., Chikowo, R. & Giller, K. E. Participatory action research (PAR) as an entry point for supporting climate change adaptation by smallholder farmers in Africa. Environ. Dev. 5, 6–22 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Gérin-Lajoie, J. et al. IMALIRIJIIT: a community-based environmental monitoring program in the George River watershed, Nunavik, Canada. Écoscience 25, 381–399 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Nussey, C., Frediani, A. A., Lagi, R., Mazutti, J. & Nyerere, J. Building university capabilities to respond to climate change through participatory action research: Towards a comparative analytical framework. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 23, 95–115 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Moss, R. H. et al. Evaluating knowledge to support climate action: A framework for sustained assessment. Report of an independent advisory committee on applied climate assessment. Weather Clim. Soc. 11, 465–487 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Zaneti, L. A. L., Arias, N. B., de Almeida, M. C. & Rider, M. J. Sustainable charging schedule of electric buses in a University Campus: A rolling horizon approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 161, 112276 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Ramchunder, S. J. & Ziegler, A. D. Promoting sustainability education through hands-on approaches: A tree carbon sequestration exercise in a Singapore green space. Sustain. Sci. 16, 1045–1059 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Evans, J. & Karvonen, A. ‘Give me a laboratory and i will lower your carbon footprint!’-Urban laboratories and the governance of low-carbon futures. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 38, 413–430 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Martek, I., Hosseini, M. R., Durdyev, S., Arashpour, M. & Edwards, D. J. Are university “living labs” able to deliver sustainable outcomes? A case-based appraisal of Deakin University, Australia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 23, 1332–1348 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Heinrich, W. F., Habron, G. B., Johnson, H. L. & Goralnik, L. Critical thinking assessment across four sustainability-related experiential learning settings. J. Exp. Educ. 38, 373–393 (2015).

-

Schneller, A. J., Johnson, B. & Bogner, F. X. Measuring children’s environmental attitudes and values in northwest Mexico: Validating a modified version of measures to test the Model of Ecological Values (2-MEV). Environ. Educ. Res. 21, 61–75 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Sierra, J. & Suárez-Collado, Á. The transforming generation: Increasing student awareness about the effects of economic decisions on sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 22, 1087–1107 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Baumber, A., Luetz, J. M. & Metternicht, G. Carbon neutral education: Reducing carbon footprint and expanding carbon brainprint BT – Quality Education. In (eds. Leal Filho, W., Azul, A. M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P. G. & Wall, T.) 1–13 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69902-8_13-1.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the “100 papers to accelerate the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals” initiative.

Funding

This work was funded by Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, TÉLUQ University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L.F. conceived the study. W.L.F., S.W., J.L., J.S., I.S.R., A.S., R.A., J.H.P.P.E., M.K wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leal Filho, W., Weissenberger, S., Luetz, J.M. et al. Towards a greater engagement of universities in addressing climate change challenges.

Sci Rep 13, 19030 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45866-x

-

Received: 04 May 2023

-

Accepted: 25 October 2023

-

Published: 03 November 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45866-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.