Picture Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington sitting in their favorite Philadelphia pub, discussing whether or not the government should be able to enact regulations mandating seatbelts in cars, rear underride guards on trailers, positive train control on trains and emissions systems on diesel engines. This vision does not require the suspension of disbelief. The fact that none of this technology existed in 1788 when the Constitution was ratified is irrelevant. The basis of our government is that original Constitution, enacted long before our modern technology world.

In 2003, The U.S. House of Representatives published a great summary document, “Our American Government.” In usual government fashion, where the Constitution is a concise six pages in total, the House document stretches to 132 pages. The summary begins with perhaps a most critical question on everyone’s minds: What is the purpose of the U.S. government?

The House concludes, “The purpose is expressed in the preamble to the Constitution: ‘’We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.’”

Tall orders trying to simultaneously do all these things in a country full of rugged individualists who value freedom. The Constitution and Bill of Rights predate all of trucking’s technologies. The closest thing to a truck in 1778 was a wagon pulled by a horse. Yet here we are at the end of 2023 arguing over whether or not the government can intercede on our behalf to protect us from ourselves on a range of technology issues like speed limiters, side underride guards, emissions, automotive braking systems and more.

The fundamental arguments regarding regulations always seem based on three pillars: profits, jobs and lives. Anything that reduces profits is an immediate red flag. Manufacturers, suppliers, industry groups and investors generally resist mandated technology as a threat to profitability. Groups argued for decades against requiring seat belts in vehicles, and argued against laws requiring actually using the seat belts. It’s estimated that less than 15% of people actually used seat belts in 1980. Now, it’s over 90%, 49 out of 50 states have laws requiring seatbelt use, vehicles are required to have seatbelts installed at the factory, and they actually have to meet standardized performance requirements. Oh, and for cars, airbags as well. One source states the automotive death rate in 1937 was 30.8 deaths per 100,000 population, where today it is 14.3 per 100,000, an estimated 54% reduction. Government regulations certainly played a role in that reduction — everything from safety technology requirements on vehicles, speed limits on roads, construction requirements for infrastructure like highway barriers, and more. Did America’s Fab Four, John, George, Ben, and Tom, and all their associates foresee a significant role of government was in protecting us from ourselves?

Does the government have the responsibility to protect us from ourselves? Should a government be able to post a speed limit? What if I want to go faster? Shouldn’t I be free to do so irrespective of the risks to myself and others? I’m not aware of a single region in the U.S. today where choosing my own speed is legal, not even Montana where rules once allowed drivers to determine their own reasonable and prudent speed.

If the majority of us today seem to accept that speed limits and seat belts are a viable role for government, then why is there so much argument over regulating emissions? It’s okay to protect us from our desire to go too fast and our tendency to get into accidents, but it’s not okay to protect the air we breathe?

Arguments that pit profitability and jobs against safety seem to lose over time. Sometimes the arguments can last decades, like with seat belts, but there are many examples where safety eventually wins out. When asked straight out, which is more important, a life or profits, it’s very challenging to root for profits, especially when you or a loved one are the life in question.

Mountains of legal documentation and regulations apply to cars and trucks today. Everything from standardizing the height of headlamps to standardizing the fuel we burn in our internal combustion engines. We are where we are today — where ever that is — because of regulations.

For example, current model year semi-trucks and their trailers are capable jointly of exceeding 10 mpg. When I started in this industry in 1980, a good day for a semi going down hill with a tailwind was probably 5 mpg.

That fuel economy improvement came through an evolution of mandated emissions improvement over three decades. Yes, market forces were also involved, but the bulk of the heavy innovation lifting came from ever stringent new standardized emissions regulations.

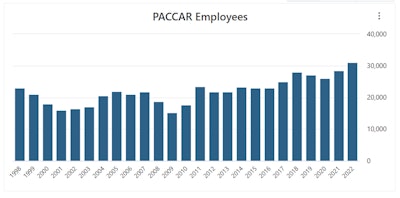

Those new technologies added cost and impacted jobs, right? One example company is PACCAR, makers of Kenworth, Peterbilt and DAF trucks. Here is an example of employment at PACCAR over time provided by the website Stock Analysis. The troughs in 2001 and 2009 coincide with the dot.com bubble bursting and the Great Recession, not emissions regulations.

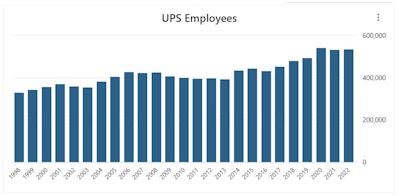

How about employment at a fleet like UPS? The graph from Stock Analysis shows no particular troughs around emissions regulation dates.

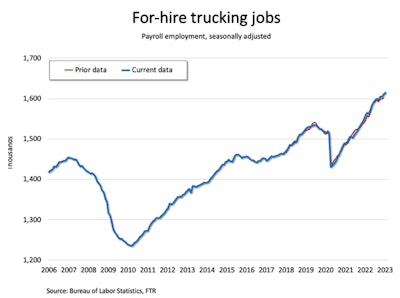

How did regulations impact the number of for-hire drivers? Avery Vise, FTR’s vice president of trucking, published this curve on for-hire trucking job trends over time. Again, the troughs are not due to regulation, but external events including the Great Recession in 2009 and the COVID pandemic in 2020.

Did emissions regulations impact sales? They certainly impacted sales through industry pre-buys, like in 2006 ahead of the 2007 EPA regulations as seen in the St. Louis Federal Reserve data on heavy-duty truck sales over time. Many factors contribute to peaks and valleys in sales of new trucks, and regulations have surely contributed to some of those.

Did regulations impact profitability? That one is pretty challenging to answer. At the macro level, the nation’s freight still moved during every regulatory implementation. At the micro level, as at any time, some companies profited, others just survived and others failed. That is the nature of business.

Those working in the trenches at truck manufacturers and fleets have always had to deal with the ramifications of new technologies required to comply with new regulations. Have they ever seen a requirement that ultimately wasn’t met by industry? Have there been bridges too far in requirements? Did the technologies ever prove infeasible to the task? There probably are some examples, like the original implementation of shorter stopping distances that led to a requirement for ABS systems on trucks in the late 1970s that was overturned in the Supreme Court ruling in 1978. But the story there ultimately was just a delay as the technology matured and again became a requirement in 1997 on all new tractors and on trailers in 1998.

Those four trucking experts, George, John, Tom and Ben, along with their many associates, created this government we all are responsible for. The fundamental basis of which is that disagreement is inherent in a democracy and required to eventually reach consensus. That discourse includes providing comments on pending regulations, testifying, court challenges, research, data, politics and emotion.

Doubtless there are a number of researchers who have published detailed reports on the ramifications of vehicle regulations on profitability, jobs and safety. I also suggest taking an empirical first-hand view. A friend of mine has a 1928 Model A and a 1966 Buick, and I’ve driven both. I’ve been in a 1939 Peterbilt, and a 1980 Freightliner COE. My feeling is that regulations have significantly improved these types of vehicles, and somehow Ford, Buick, Peterbilt and Freightliner are still in business.