This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

The war in Ukraine has reached a critical point. Where it goes from here could decide the country’s future and affect the security of Europe.

In the 18 months since Russia invaded, the Ukrainians have mostly been on the defensive, preventing Moscow’s forces from seizing more territory.

But this summer, Ukraine – with the help of billions of pounds of Western military equipment – has gone on the attack, attempting to expel the Russians from land they previously captured in the east and south of the country.

Two months into this counter-offensive, and with time of the essence before the onset of winter, are Ukrainian troops making any real progress?

Working with BBC Verify, we have analysed video of the fighting and spoken to experts to try to answer that question.

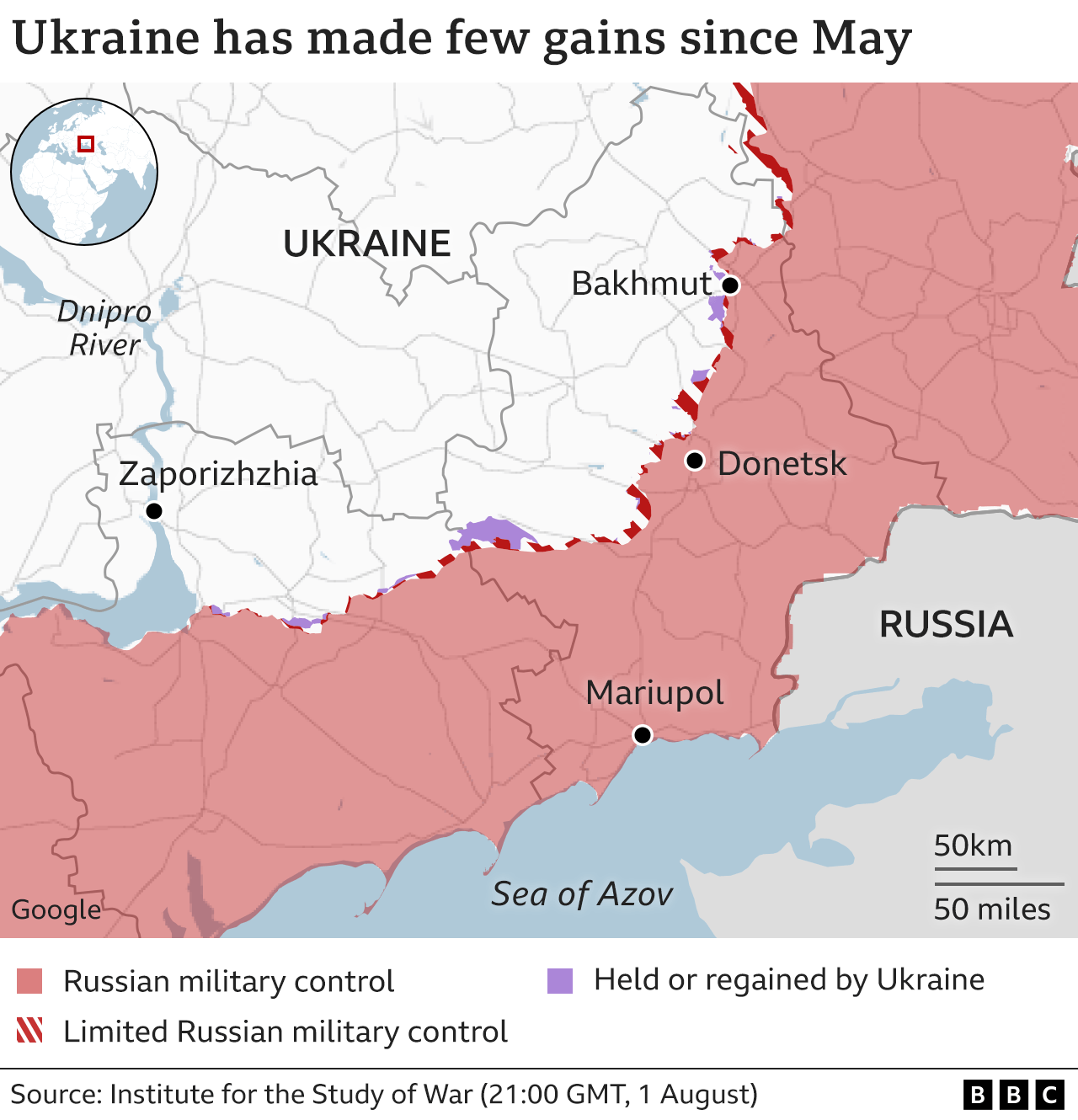

One look at a large-scale map of eastern and southern Ukraine shows that not much has changed in the two months since the counter-offensive began.

Russia still occupies nearly one-fifth of Ukraine – including the cities of Donetsk, in the east, and Mariupol, which it captured after months of siege – and its forces are well dug in.

In fact, not much has changed in the nine months since November 2022, when Ukraine made its last significant gain, retaking the southern city of Kherson and large areas in the north-east.

But it hasn’t all been bad news for Ukraine.

It says its troops have recently retaken the village of Staromaiorske in the Donetsk region. The BBC has verified video which supports that claim.

Around Bakhmut, in the east, where there has been intense fighting, Ukraine has also regained some small areas that it lost earlier in the summer.

And it has also made small gains in the Zaporizhzhia region in the south – a key area where Ukraine really needs to make a decisive difference.

A Ukrainian push through the swathe of Russian-held territory to the Sea of Azov would disrupt Russia’s supply routes and cut off their forces in Russian-annexed Crimea and further west.

The map below shows where ground has been retaken. The large red areas indicate Russian-controlled areas, the purple ones are territory held, or regained, by Ukraine. The black circles show just how heavily the Russians have fortified this region.

The city of Tokmak, for example, has a ring of fortifications around it – as BBC Verify revealed in May.

Why is Ukraine’s progress so slow?

In two months Ukrainian troops have advanced, at most, about 10 miles (16km) in two areas along the region’s 100-mile (160km) front, according to independent analysis.

Progress is being made, but it is slower than Ukraine and its Western allies had hoped.

Ukrainian forces have been attacking on three fronts, using Western-supplied equipment and training, and probing for weak spots along the entire 700-mile (1,125km) front line.

But the Russians foresaw their intentions, and they have spent months building the most extensive fortifications in recent history.

Triple layers of trenches, bunkers, concrete pyramid tank-traps (so-called “dragon’s teeth”) and ditches – laced with thousands of landmines – present a massive obstacle to any Ukrainian advance, as illustrated in the satellite image below, taken near Tokmak.

Marina Miron, a defence expert at King’s College London, says Ukraine has had to scale back its ambitions in the south, including aspirations to take back Crimea.

“I don’t think that will happen anytime soon,” she says.

Dr Miron says the best they can hope for is potentially retaking Tokmak, which lies on a key route in the south-east of the country – an area which acts as a logistical hub for Russian forces.

- No fast results in offensive, warns Ukrainian commander

- Satellites reveal Russian defences before major assault

Back in June, Ukraine sent an armoured column south towards Tokmak and quickly ran into trouble.

Videos shared on social media, which BBC Verify cross-checked to compare locations and the types of military vehicles, showed newly-supplied western Leopard tanks and Bradley fighting vehicles hitting a minefield and then being attacked by Russian artillery.

The Russian army appears to have recovered from some of the mistakes it made during the first 12 months of the invasion, and is proving to be surprisingly innovative and effective in defence.

Russian defensive tactics

Lots of anti-tank mines are being used, for example.

Western-supplied mine-clearing vehicles can usually withstand one hit from these mines, but not two. So the Russians are reportedly laying one on top of the other to double the effect.

The Russians have also started booby-trapping trenches.

In a video, verified by the BBC – but which is too graphic to show, you can see Ukrainian infantry entering empty trenches south of Zaporizhzhia, before hidden explosives are detonated, blowing up some of the troops.

- ‘Russia said I was dead’ – voices of Ukraine’s front-line women

- Ukraine’s invisible battle to jam Russian weapons

The Russian military is also taking advantage of its air power – such as using its Ka-52 Alligator attack helicopters.

These helicopters can be used to fire rockets at Ukrainian armoured vehicles which have been forced to slow down or stop after encountering a minefield.

And Ukraine – it’s worth noting – does not have air superiority over the battlefield.

What next for Ukraine’s counter-offensive?

While Russia was building its defences, Ukraine was putting together a dozen, newly-formed armoured brigades, many of them trained in Europe and supplied with better equipment than the Russians.

Ukraine now has the capability to launch missiles, rockets or shells deep behind Russian lines – hitting their fuel depots, ammunition hubs and command and control centres, which could weaken Russia’s defences from within.

This British-supplied Storm Shadow missile, for example, has a range of more than 150 miles (240km), and has enabled Ukraine to push some of Russia’s positions further away from the front line.

Ukraine is also using US-supplied cluster munitions.

Many don’t explode on impact and remain a long-term hazard, but the US says they are proving effective against some entrenched Russian positions.

However, Gian Luca Capovin, an analyst with Jane’s Defence, says cluster weapons can help, but won’t be “a game-changer.”

Russia also has its own cluster weapons, and has also deployed them as we reported last year.

Ultimately, time is not on Ukraine’s side.

By autumn, the rainy season will have arrived, turning unpaved roads into mud and making further advances difficult, if not impossible.

By the time that ends, in the spring, the US presidential election cycle will be under way.

If Ukraine cannot show any decisive gains on the battlefield by then, it is far from certain that US and Nato support will continue at their current high levels.

For Kyiv, the clock is ticking. Meanwhile Russia simply has to hang on to the territory it has illegally seized.

Additional reporting by Benedict Garman, Thomas Spencer, Tural Ahmedzade and Filipa Silverio.

Related Topics

- Russia-Ukraine war

- Russia

- Ukraine