I’ve been there many times: engaged in conversation with a car enthusiast where attempts to promote or even mention transit alternatives hit an aggressive roadblock. The person I’m talking with refuses to acknowledge whatever facts I offer or deflects my argument with ambiguous generalizations such as that proposed policy prescription “sounds great in theory, but no matter what we do it’s impossible to eliminate all traffic deaths,” or, “bikes are great, but you can’t get places without driving at some point.”

Why do seemingly harmless suggestions to make space for safe car alternatives lead to such entrenched stances? The answer lies in denialism.

Denialism has its roots in the politics of climate change. It is the rejection of evidence-based arguments, established facts and consensus viewpoints in order to maintain a preconceived belief or ideology — typically through a pattern of avoidant rhetoric. Scientists have studied the concept enough to map out a framework its adherents use to sow confusion: fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations (moving goalposts), conspiracy theories, and selectivity (cherry picking). The academic world refers to this framework as FLICC. Denialism rears itself in bike debates and fuels opposition to alternative transportation.

Fake experts

Fake experts present the veneer of expertise, technical training, and knowledge — but have none of these.

Traffic engineers are a frequent source of fake expertise in transportation. These professionals typically have advanced degrees and official titles, and adhere to volumes of safety standards. But their standards derive from skewed models or nothing at all, city planner Jeff Speck has written. Engineers often push for policies, like more car lanes, that make streets less safe and disregard the needs of pedestrians and others.

In his 2010 essay “Confessions of a recovering engineer,” Charles Marohn put a fine point on this, saying that as a traffic engineer, he often pushed for bad ideas simply “because that was the standard.”

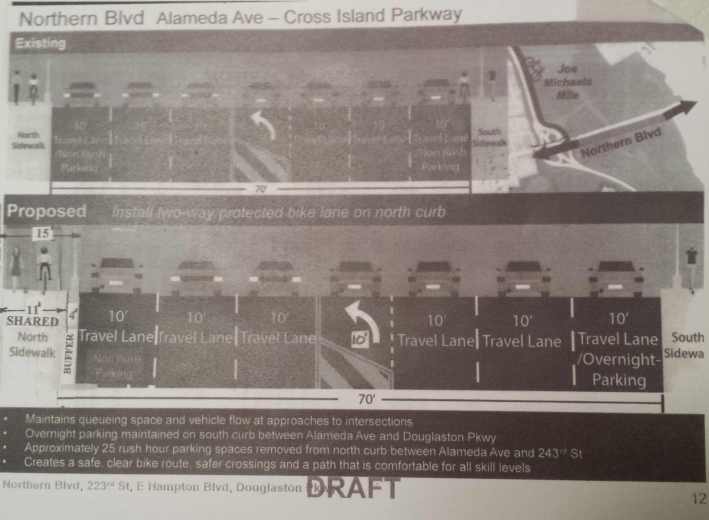

Fake experts have tried to derail street redesign projects in New York City. Bernie Haber, former co-chair of the Queens Community Board 11 transportation committee, is a prime example. Haber is a retired transportation engineer — a background that suggests expertise. In 2017, he attempted to undermine CB 11’s vote in favor of a protected bike lane on Northern Boulevard. Following the board’s endorsement of the project, Haber quickly pulled together a transportation committee meeting to give a lengthy presentation on a proposed alternative that conveniently preserved parking and eliminated the crucial safety measure of narrowing travel lanes. Luckily, city officials saw through this charade, pointed out the flaws in Haber’s proposal — and installed the project according to their original design.

Logical fallacies

Logical fallacies are arguments built on an unsound logical foundation. Former Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe famously demonstrated this in 2015 when he brought a snowball to the Senate floor and suggested that because it was cold enough to produce snow, climate change was a lie. His argument overlooked vast scientific evidence.

In transportation, logical fallacies arise regarding the usage of bike lanes. When the city installed the Prospect Park West bike lane in 2011, opponents claimed that nobody rode in it because of how empty it appeared. But bike lanes are incredibly efficient. They generate no traffic unless there are astronomical numbers of cyclists in them. This can easily be perceived as “emptiness,” but does not mean the bike lane is not used. A 2009 DOT study showed that weekday and weekend cycling on the street increased by more than 100 percent following the installation of the lane — more recent bicycle counts show a continued increase since.

Impossible expectations (moving goalposts)

Impossible expectations, or moving goalposts, thrive in arguments about highway and street expansions. States spend billions on highway expansions every year with the hope that this will reduce traffic and congestion. These efforts inevitably fail because of induced demand — more lanes encourage more driving, and traffic remains bad or gets even worse.

The idea that drivers should move as fast as possible sets an impossible goal that they never hit any traffic. Yet Gov. Hochul has touted this exact argument in defense of the expansion of Upstate’s Route 17, insisting it will “[improve] quality of life by alleviating congestion.” History — and data — indicate that this will not be the case. But Hochul, by setting the moving goalpost of “no traffic,” upholds the unrealistic expectation that we can add lanes to eliminate traffic.

Bike lane opponents also utilize this tactic when they demand infinite levels of community engagement. The goalpost moves with every new demand for additional feedback. On Underhill Avenue in Brooklyn, for example, DOT began collecting local input on a possible street redesign community engagement in 2021. Between 2021 and 2024, opponents pushed DOT to revise the proposal three times, demanding additional community input with each iteration. The city’s combined outreach totalled two online surveys, five DOT on-street workshops and four presentations to the local community board over three years. Yet even after DOT began installation, Mayor Adams made them stop — and insisted that city bureaucrats collect even more input. Despite nearly three years of outreach, the street redesign has not been completed.

Conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories proliferate among alternative transportation opponents. In October 2023, a listener called into WNYC to claim that tech companies have taken over the city Department of Transportation. Advocacy groups like Transportation Alternatives have indeed received some funding from tech companies, and it is true that these organizations lead campaigns to push for safe, equitable streets. But this is a far cry from the notion that Transportation Alternatives or any other advocacy group secretly controls DOT. If they did, how do opponents explain DOT repeatedly ignoring those organizations’ policy priorities and recommendations? Uber and Lyft, meanwhile, have actually turned against congestion pricing — putting them at direct odds with advocates.

Similarly, right-wing conspiracies skyrocketed in recent years around the idea of “15-minute cities.” This concept adjusts city planning such that every resident can meet their needs within a walkable area close to home. Skeptics wrongly insist that bureaucrats support 15-minute cities because they want to control where people can drive. In fact, there are no movement restrictions associated with 15-minute cities. The concept simply aims to provide residents with the things they need — like grocery stores, medical care, and employment — close to home, rather than banishing working people to far-off exurbs.

Cherry-picking

Cherry-picked evidence leads to a skewed version of reality and obstructs informed decision-making. Anti-e-bike advocates often use cherry-picked examples to fuel their arguments. Members of the E-Vehicle Safety Alliance repeatedly point to the story of Pamela Manasse — who was seriously injured by a moped rider — as evidence that all e-bikes should have license plates or be banned completely.

But a single example does not imply a broader trend. E-bike opponents purposefully ignore hundreds of people killed or injured by cars in New York City in favor of highlighting one or a few examples that support their cause. This lets them assert that the cherry-picked example is actually the norm, giving the appearance of integrity while helping advance their agenda.

In the case of the E-Vehicle Safety Alliance, this means banning or restricting e-bike use. Council Member Robert Holden has proposed legislation to require licensing and registration for all e-bikes. This legislation will be extremely harmful if it becomes law — likely cutting e-bike use, increasing motorcycle and car emissions and traffic, and forfeiting economic benefits associated with micro-mobility.

How advocates can respond

So how can advocates and planners navigate the FLICC framework within the context of drivers and transportation? The first step is to acknowledge the denialism underlying immovable pro-car stances. Facts cannot change the minds of denialists or shut down their arguments.

Diane Benscoter, an expert in cult deprogramming who helps people untangle from extremist ideologies, argues that group ideological stances have great appeal because they offer camaraderie and a feeling of righteousness that comes with fighting for a cause — from a fundamental human need for belonging and purpose, which draws individuals into a sense of community and shared identity. Paradoxically, the aversion to being deceived often surpasses the discomfort of no longer being part of the group. Instead of fixating on the merits of particular concerns, advocates should persuade individuals that they have been deceived.

This process doesn’t always happen quickly. Deep-seated beliefs are difficult to uproot. Progress requires a concerted and consistent effort. Car-first policy sympathizers need to be confronted by the deceit lurking within the promises of car-dependency and driving.

Such large-scale cultural shifts in the perception of an issue are much more common than one might think. The public perception of cigarettes, marriage rights, reproductive rights and climate change all shifted significantly in the last two decades. Driving should be next.

As an example, the U.S. auto industry significantly shaped government policies towards cars and perceptions of driving, infrastructure and other modes of transportation. Auto manufacturers even created the term “jaywalking” as part of a campaign to assert drivers’ rights to speed down streets with no consequences. This history contradicts many Americans’ foundational beliefs about the issue — namely, thqat policymakers should prioritize driving as the superlative mode of transportation. Stubborn drivers cannot avoid reality if the discourse around transportation and street usage is saturated with facts.

Personally, I think it is impactful to call out and name denialist rhetoric when I see them. This happens at community meetings, on social media and more. There is strength in saying, “I’d like to point out that this person continues to move the goalposts. As soon one concern gets an adequate response, they move to a different concern. They may never be satisfied.” This takes power away from detractors and helps win over the crucial audiences of fence-sitters, neutral bystanders and otherwise impartial observers.

We can change minds by calling out rhetoric and sowing seeds of doubt about the origin of pro-driving stances. I’ve noticed changes in my interactions with neighbors and friends in Prospect Heights over several months of dialogue. Individuals I couldn’t even broach this subject with months ago now send me news articles on transit developments.

Every case is different, but I strive to cultivate a discourse where there is zero tolerance for denialist rhetoric. Pro-car detractors and drivers ought to have the soundness of their beliefs repeatedly called into question. We must confront the impetus behind their concerns: Why do they think parking is important to a conversation about livability and safety? What beliefs caused them to ask that question and what are their origins?

These actions form a recipe for a more productive landscape and both short and long term shifts in perceptions of street issues. By unraveling misunderstandings and misinformation with a deliberate and clear approach, anyone can be swayed.