By Trevor Fairbrother

It is a great gift that the Gardner Museum has made such a strong and lively exhibition, presented exclusively in Boston, devoted to Manet.

Manet: A Model Family at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, through January 20.

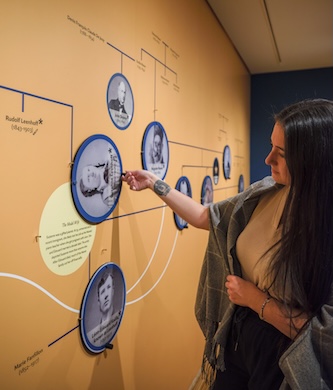

View of the family tree in the anteroom of the exhibition Manet: A Model Family. Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Lovers of Édouard Manet (1832–1883) treasure the few major works on permanent display at the Museum of Fine Arts, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and Harvard Art Museums. His canny genus of painterly painting offers an aesthete’s fixation on select “Old Masters” working in sync with a firebrand’s fight against old fogeys at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He inspired generations of figurative artists from John Singer Sargent and George Bellows to Alice Neel and Marlene Dumas. How many times have local museums devoted an exhibition to Manet in the last 150 years? The only one I remember was a low-cost but excellent presentation of his prints at the MFA in 2012 – it was under-celebrated and installed in a hallway. It is a great gift, then, that the Gardner has made a strong and lively show, presented exclusively in Boston: Manet: A Model Family is on view through January 20, 2025.

Diana Seave Greenwald, the museum’s Curator of the Collection, organized the show and edited the accompanying publication. The germ for her project was Madame Auguste Manet, the arresting black-on-black portrait of the artist’s widowed mother that Mrs. Gardner purchased from a London dealer in 1910. This regal homage dates from the period when the wealthy matriarch gave her son Édouard the funds to produce a solo exhibition and catalogue in a custom pavilion near the Paris World’s Fair of 1867.

View of “Act 2” (Fishing) in Manet: A Model Family. Photo: Trevor Fairbrother

Some may think Greenwald’s subtitle – “A Model Family” – characterizes the Manet clan as exemplary or archetypal. In fact, its peculiarities were elaborately piquant. So perhaps the subtitle is a play on the artist’s habit of using his relatives as models. Manet mère (Eugénie-Désirée) hailed from a prominent diplomatic family and Manet père (Auguste) held high office in the Ministry of Justice. Édouard’s kinsfolk felt he married beneath his station, even though the woman he chose was a piano teacher hired by his parents in 1849: Suzanne Leenhoff (1829-1906). The snooty Manet circle frowned on the fact that she was a recent Dutch immigrant and moderately plump in person. Whilst in their employ she conceived a child out of wedlock: Léon Leenhoff (1852-1927). Léon’s biological father has not been identified, but today’s scholars are inclined to speculate it was Manet père; however, it may have been Édouard or one of his two younger brothers. In public, Suzanne pretended that Léon was her brother; indeed, the engraved cards for her funeral identified him as such. Édouard married Suzanne in the Netherlands in 1863, the year after his father died of complications from syphilis. The same disease killed Édouard in 1883.

The museum rightly proclaims this exhibition as “the first examination of [Manet’s] innovative artwork … in the context of his complex family relationships. At the same time, Greenwald generously acknowledges the pathbreaking importance of Nancy Locke’s 2001 book Manet and the Family Romance. Of the 15 paintings by Manet on view at the Gardner, 11 were illustrated and discussed in Locke’s study. (Appropriately, Greenwald invited Locke to write an essay on Madame Auguste Manet for the catalogue.) I hasten to add that the show also features numerous works on paper, and assorted archival materials and historic photographs documenting the dispersal of the estate. There’s even a small foray into the realm of tampering. For example, the label for an unfinished painting of Suzanne (c. 1873, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art) indicates that Manet’s heirs had it retouched to make it more saleable. The exhibition also includes an early copy of the masterpiece owned by Nationalmuseum, Oslo: Madame Manet in the Conservatory, 1879. The replica was painted for Suzanne after she sold the original to a French dealer/collector in 1895.

Édouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871. Photo: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

In my estimation the following canvases, listed in chronological order, make the exhibition outstanding:

- Monsieur and Madame Auguste Manet, 1860. The artist’s unsmiling parents at home; they are lost in private thoughts yet visually and emotionally dovetailed within the composition.

- Fishing, about 1862-1863. A fantasy pastoral setting with lake or river; Édouard and Suzanne are conjured by the Rubenesque couple, and Léon by the blonde boy in the background.

- Madame Auguste Manet, 1866. A boldly brushed portrait of the matriarch wearing widow’s black and gazing confidently at the viewer.

- Boy Blowing Bubbles, 1867. Léon was the model for this tender and disarming figure study, which harks back to France’s incomparable Rococo artist Jean Baptiste Chardin.

- Young Boy Peeling a Pear, about 1868. Adolescent Léon, in modern attire and sporting a moustache, prepares to enjoy a pear; art historical allusions and symbols of the senses augment this picture’s power to enchant.

- Madame Manet at the Piano, 1868. Suzanne performs in the white and gold paneled salon of her mother-in-law; the clock reflected in the mirror was a wedding gift from the king of Sweden in 1831.

- Interior at Arcachon, 1871. In March, after the end of the siege of Paris, Édouard, Suzanne and Léon enjoyed a month by sea, south of Bordeaux; the wife, seen from behind, gazes out to the horizon; her son is lost in thought, an open book in his lap.

- The Croquet Party, 1871. This idyllic frieze-like view of the leisure class at play memorializes a vacation in Boulogne; Léon stands at the center, in brown trousers, Suzanne at the right; all in gray; the woman in black might be Manet’s mother.

- Reading, 1868-73. Suzanne first posed for this fetching and flattering likeness in the late 1860s; the artist reworked it a few years later, adding the towering plant at left and figure of Léon, in silhouette, at right.

- Berthe Morisot, 1869-73. Morisot, a painter who shared Manet’s progressive artistic ideas, was his favorite model from 1869 until 1874, the year she became his sister-in-law; the broad, fast brushstrokes foster a sense of instantaneity and improvisation.

Manet: A Model Family takes place in the Gardner’s 2012 extension by Renzo Piano. The space for special exhibitions begins as a low, narrow foyer, known as the anteroom, which has two doorways into the airy 45-feet-square gallery. For Manet the north-facing glass curtain wall has been covered and a temporary wall is positioned in front of it. In the center a free-standing construction of two intersecting walls provides corner-like pockets where pictures can be paired to advantage.

Édouard Manet, Boy Blowing Bubbles, 1867. Photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

The first work one encounters in the corridor-like anteroom is The Croquet Party. It hangs next to a fetching bust-length portrait of Manet painted in 1876 by Carolus-Duran (whose most assiduous student was Sargent). Facing these canvases is an interactive learning station that maps connections between family members and close associates: visitors are invited to slide up the circular mugshots to find snippets about the person. Here’s an example:

The Mystery: As a teenager, Léon learned that Suzanne, the woman he thought was his sister, was his mother. He likely never knew the identity of his biological father. Léon was a frequent model for Édouard. He promoted the painter’s legacy – even when the Manet family excluded him.

In the main gallery the signage proffers a narrative thread that unfolds in these themes:

Act 1. Old Masters, New Family

Act 2. Three Manet Women

Act 3. Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder

Act 4: Keeping the Manet Legacy

Each section is pinpointed by a text panel flanked by a giant photograph of a small detail from a key work. The painting hangs in the middle of the enlarged close-up of Manet’s brush work. For example, the photomural for “Act 2” shows the bottom left corner of Fishing, including the painted signature. HER Design, the local consultancy that devised and fabricated the Gardner’s display, honed its perky upbeat brand working for such clients as Nantucket Whaling Museum and Nahant Historical Society. I didn’t warm to all the gimmicky embellishments, but they’re bearable since being in the presence of works of this caliber is a tremendous pleasure.

After experiencing and digesting Greenwald’s numerous achievements, it is tempting to chime in with afterthoughts. My pipe dream would be to do a makeover in which Léon holds the center. I’d title it About a Boy (thank you Nick Hornby) and wonder about how the other characters in this Manet show treated him. I like this sentence in the Gardner’s press release: “While Édouard, Suzanne, and Léon were a happy family trio, the tension between revelation and obfuscation lay deep in Manet’s family life and art.”

The catalogue for Manet: A Model Family is most commendable: seven smart essays of various stripes; numerous full-page details of great pictures; a chronology and biographies of family members; engaging catalogue entries on the paintings by Manet on view at the Gardner; and, last but not least, an index that works like a charm.

In 2003 Trevor Fairbrother was guest curator of the exhibition Family Ties: A Contemporary Perspective at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA; he also wrote the accompanying catalogue, which reprised Sarah Vowell’s essay “What I See When I Look At The Face On The $20 Bill.” © 2024