By Lauren Kaufmann

The show may be a case of inside baseball, appealing to a small group of art history majors and museum lovers. But it offers a fascinating look at innovation at one of the country’s most revered, and most traditional, colleges.

The Art of Looking: 150 Years of Art History at Harvard, at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, through May 11.

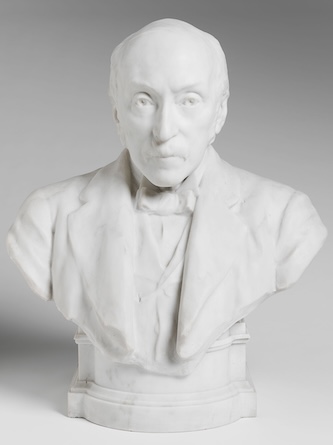

Victor David Brenner, Charles Eliot Norton, 1906. Marble. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

The Art of Looking: 150 Years of Art History at Harvard celebrates the evolution of Harvard’s Art History Department. The exhibit may be a case of inside baseball, appealing to a small group of art history majors and museum lovers, but I also see it as a fascinating look at innovation at one of the country’s most revered, and most traditional, colleges.

I was surprised to learn that Harvard offered art history electives back in 1874, becoming the first American college where students could study art history. I wasn’t surprised by Harvard’s emphasis on material culture. That’s because after my junior year in college I attended Harvard Summer School, where I took a course in Chinese art. I remember spending as much time in the old Fogg Museum, scrutinizing ancient bronzes and scroll paintings, as I did attending lectures. It was a refreshing break from the conventional study of art history.

As an art history/religion double major, I spent many hours scribbling notes in a darkened lecture hall while viewing a carousel of images — soaring Gothic cathedrals, epic tapestries, medieval Madonnas, Renaissance Madonnas, and every modernist movement imaginable. My study of Buddhism sparked an interest in Asian art, which led to my enrolling at Harvard. At the small liberal arts college that I attended, professors didn’t take students to museums to see the artwork and objects that we were studying. We learned by reading about artistic movements and viewing images projected on the screen.

Because of the Fogg’s strong collection, Harvard students have been fortunate to have access to many outstanding examples of the works they are studying in art history class. Although the exhibition doesn’t mention this, the Fogg was not established as a place to display art and artifacts; it was originally intended as a place for students to learn about the visual arts. There were classrooms, a library, an archive of slides and photographs of works of art, and a gallery for reproductions of works of art. The Fogg Museum opened to the public in 1896.

The Constellation Serpentarius (recto). Illustrated folio from a manuscript of the Kitab Suwar al-Kawakib by al-Sufi, Iran, 15th century. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908) pioneered the study of art history at Harvard. The wall text tells us that he believed that students needed to learn how to look at art, and that learning how to draw was critical to their ability to analyze art. Charles Herbert Moore (1840-1930) taught drawing, while Norton adopted a hands-on pedagogy, supporting it with examinations of objects from the Fogg Museum and visits to the Museum of Fine Arts. Both men saw the museum as a kind of laboratory that encouraged students to engage with three-dimensional objects, while considering the human inspiration and skill that went into the work.

A clunky old slide projector serves as a relic of the days when “audiovisual” was a newfangled term. A glass case contains several objects, including a small booklet, bound with knotted twine, with lecture notes from the 1923-24 academic year. Written in longhand by a Professor Pope, the booklet makes you stop and wonder about how radically our modes of communication have evolved, for better or worse. These days, professors and students create PowerPoint presentations on their laptops — visual material is easily accessible on the Internet. No slides necessary.

A section devoted to English writer John Ruskin’s influence on Charles Eliot Norton emphasizes the critic’s work as a “theological geologist.” The wall text informs us that Ruskin had a deep appreciation for earthly structures and believed that “artists should have an emotional and scientific understanding of the landscape to present both moral and material truth.” A pair of watercolors by Ruskin, both architectural studies from the collection of the Fogg Museum, exemplify his belief in grasping the underlying structure of natural forms.

What the text omits is background context about Ruskin (1819-1900), an influential critic of art and architecture, whose views on aesthetics shook up the old English order. He was a fierce defender of the work of J.M.W. Turner, whose unusual landscapes (at the time) were attacked by reviewers in the early 1800s. Ruskin penned a monumental multivolume series, Modern Painters, and a three-volume set, The Stones of Venice, a detailed history of Venetian architecture. He holds an important place in art history as a critic whose views had tremendous sway at a time that the culture was rapidly changing. Sadly, the exhibition doesn’t share this background information with museum visitors, many of whom may not know much, if anything, about Ruskin.

Slide projector. Loan from the Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University. Installation view. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

A section devoted to the study of Chinese art acknowledges the role played by Langdon Warner (1881-1955), credited with being the first American scholar to study Chinese art. Although the wall text alludes to controversy regarding Warner’s removal of some objects, it goes on to praise him for introducing the study of Chinese art to the Harvard community. Professor Warner sparked major controversy when he traveled to China in 1924 and removed 26 Tang dynasty wall-paintings from the Mogao Caves. His efforts (in the name of preservation) left the site and the frescoes damaged. The Chinese government considers these artifacts to be stolen goods. There are plaques at the Dunhuang Museum accusing Warner of being a thief.

Warner also became an expert in Japanese art, and there are two lovely hanging scrolls from the 1800s that were acquired during his tenure. Warner became a curator at the Fogg, where his connections with Japanese artists and scholars were considerable benefits to the museum’s collection.

Another section is dedicated to Denman Ross (1853-1935), a Harvard professor who collected textiles throughout his travels in South America, Africa, and Central and East Asia. He used these objects to teach Harvard students to analyze design. A glass case highlights several examples of the textiles that are now in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums.

Hashimoto Gahō 橋本雅邦, Japanese, Regent Hojo Tokiyori in Disguise, Meiji period, late 19th century. Hanging scroll; ink and light color on paper. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Joseph Lindon Smith (1863-1950) is lauded for his study of ancient painted sculpture. In the early 1900s, he was commissioned to paint watercolors of Egyptian tomb reliefs from Harvard’s excavations at Giza. A professor of Egyptology at Harvard, Smith was also a curator of Egyptian collections at the MFA. He knew Lord George Carnarvon and Howard Carter, the team best known for discovering the tomb of King Tutankhamen. The exhibition includes a watercolor that Smith painted of Hapi, an Egyptian god of the Nile Flood.

The exhibition’s title suggests that it encompasses 150 years of Harvard’s Art History department, so I was hoping to learn about more recent developments. Unfortunately, the focus is limited to the founders of the department and, no surprise, they are all men. Yes, space limitations must have demanded ample calibrations about what to include and what to neglect in The Art of Looking. But I can’t help but wonder if there might have been others — perhaps some women and people of color? — whose contributions could have been included, had the curators looked hard enough.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions. She served as guest curator for Moving Water: From Ancient Innovations to Modern Challenges, currently on view at the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston.