Discussion

This study provides evidence that during the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. health workers experienced larger declines in a range of mental health outcomes than did essential and other workers, with the exception of general happiness, which was lower in essential workers. These data support the imperative for action to create a system in which health workers can thrive, as described in the U.S. Surgeon General’s 2022 report “Addressing Health Worker Burnout,” (8) which notes that distressing work environments contributed to a record high number of health workers quitting their jobs. A population-based cross-sectional study in Norway in early 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, reported lower levels of anxiety and depression among health care workers compared with other workers (13). In contrast, the current report finds that U.S. health workers reported a larger increase in number of days of poor mental health and burnout in 2022 compared with 2018 than did other workers, with nearly one half (46%) reporting burnout in 2022. U.S. health workers were also more likely than were other workers to report negative changes in working conditions during that time. In 2022, the prevalence of reported health worker harassment more than doubled, and the very likely intention to find another job increased by almost 50%. Negative working conditions are associated with higher prevalences of depressive symptoms (1,2), self-rated poor health (14), and turnover intention (8). Accordingly, the American Public Health Association††† and the International Labour Organization promote decent work§§§ (e.g., work that provides security and social protection; a fair income; and opportunities for growth, development, and productivity) as a public health goal fundamental for protecting workers.

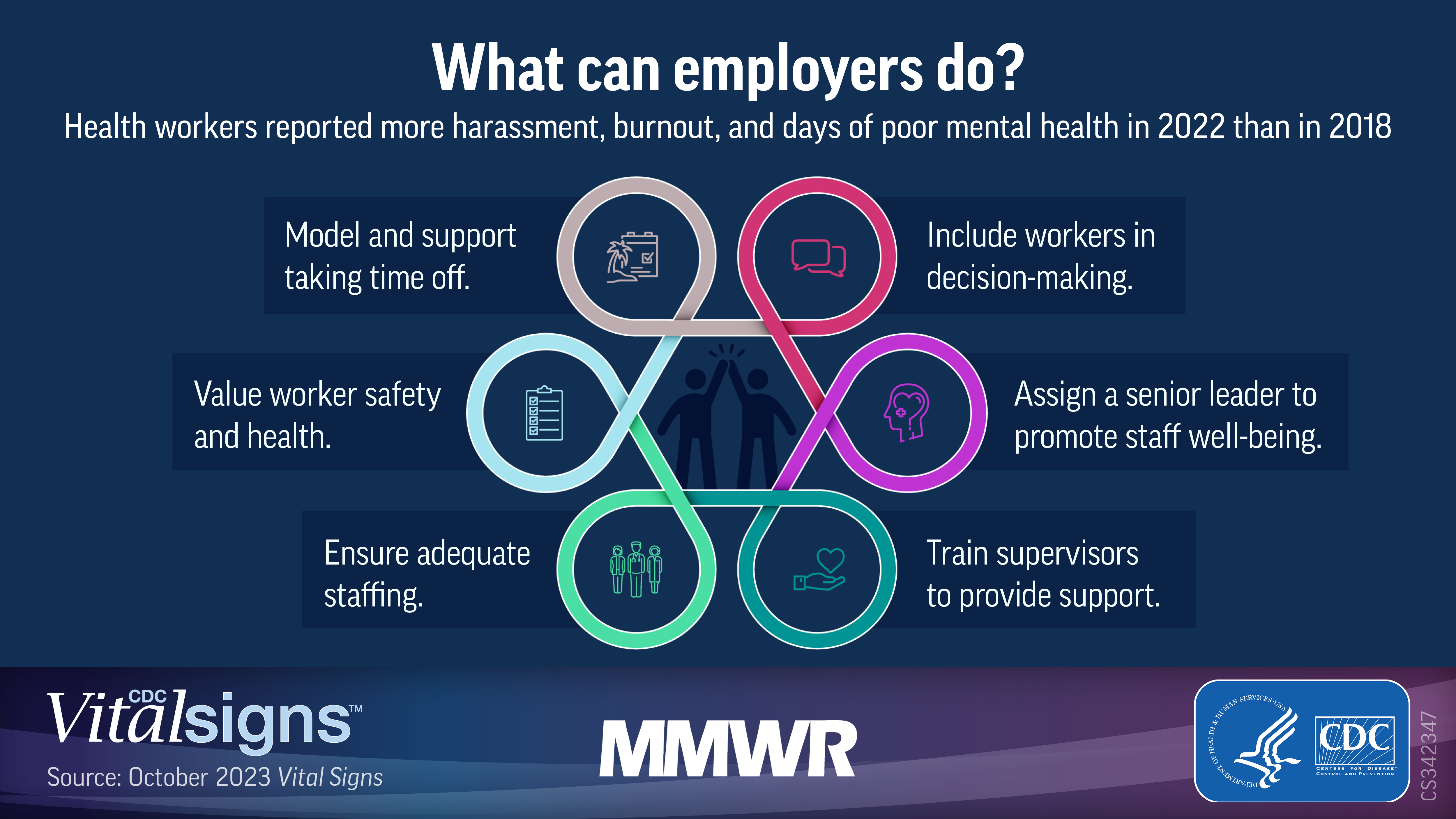

This report identifies modifiable working conditions that contributed to poorer mental health among health workers and suggests preventive actions for employers. Previous research found job stress interventions that changed aspects of the organization (e.g., increased manager social support) were more effective than were secondary (e.g., screening for stressors) or tertiary (e.g., individual stress management) (15) interventions. A recent review of management interventions suggests that training managers on mental health awareness and ways to support workers and improve safety culture shows promise for reducing worker stress and improving well-being (16). Working conditions that support productivity and foster trust in management might be more readily addressed than providing sufficient staffing, which can be challenging in resource-constrained settings. More positive psychosocial safety climates, which include management prioritization of psychological health and stress prevention, were associated with lower burnout symptoms among health workers in this study. Previous research has demonstrated the link between psychosocial safety climate and reduced exhaustion, improved worker well-being, and improved engagement (17). Organizational policies and practices can be modified to improve security and reduce threats of violence.¶¶¶ The International Organization for Standardization provides guidelines for managing psychosocial risks in the workplace to promote worker safety and health.**** Employers can also make changes that increase participation in decision-making and reduce workloads.†††† Evidence suggests that attention to such protective aspects of work could reduce the number of days of poor mental health and prevalences of burnout and turnover intention (18). Recent reviews note the limited number of organizational intervention studies addressing health worker mental health (16,19), reinforcing the need for researchers to join health employers, government, labor, and professional organizations in implementing effective organizational interventions and documenting their impact.

CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has implemented efforts to promote the mental health and well-being of health workers. One is a national social marketing campaign, Impact Wellbeing, which emphasizes primary prevention strategies such as worker participation in decision-making, supportive supervision, and increasing psychological safety for help-seeking (20). NIOSH has also developed burnout prevention training for supervisors of public health workers.§§§§ Through these efforts, as noted in the Surgeon General’s report (8), the emphasis is on improving the work environment to support mental health, rather than asking workers to be more resilient or to fix problems themselves.

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least six limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional; causation cannot be inferred, and alternative explanations for the findings are possible. Second, these data are self-reported and subject to biases associated with recall and social desirability that could affect participant response. Third, because of administration during the pandemic, the 2022 GSS used mixed methods, including face-to-face and telephone interviews, and online administration; the 2018 survey was conducted using only face-to-face interviews. Use of these different methods might have influenced response rates and self-reporting of symptoms. Fourth, data were weighted to be nationally demographically representative, but were not adjusted for industry, occupation, and work setting. Fifth, a relatively small number of health workers were included in the 2022 sample. The fourth and fifth limitations might limit generalizability. Finally, measures of symptoms for anxiety and depression were not available in 2018, which precludes prepandemic comparisons.

Implications for Public Health Practice

Health workers continued to face a mental health crisis in 2022. Improving management and supervisory practices might reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and burnout. Protecting and promoting health worker mental health has important implications for the nation’s health system and public health. Health employers, managers, and supervisors are encouraged to implement the guidance offered by the Surgeon General (8) and use CDC resources (20) to include workers in decision-making, provide help and resources that enable workers to be productive and build trust, and adopt policies to support a psychologically safe workplace.