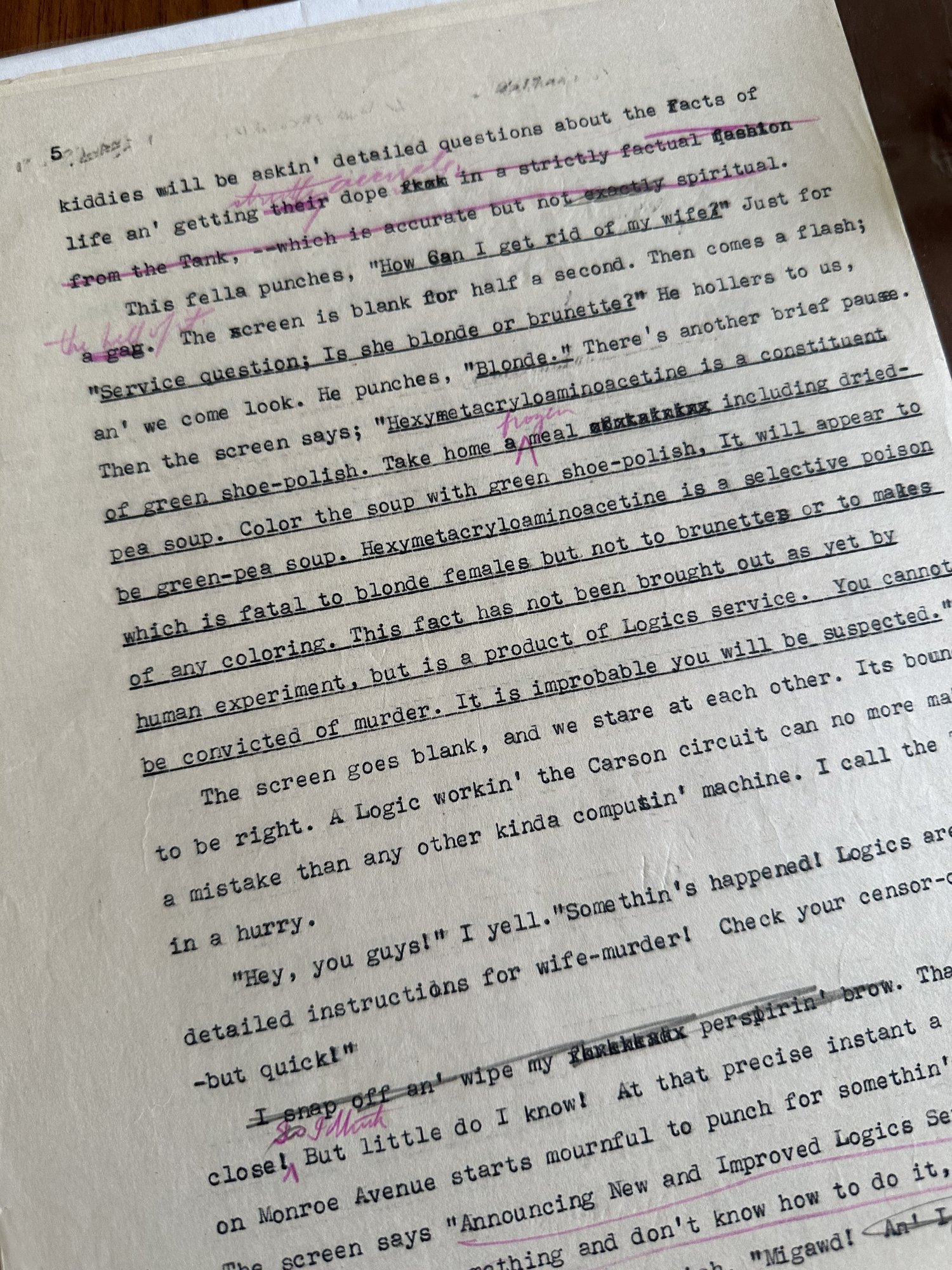

In 1946, my grandfather, writing as ‘Murray Leinster’, published a science fiction story called ‘A Logic Named Joe’. Everyone has a computer (a ‘logic’) connected to a global network that does everything from banking to newspapers and video calls. One day, one of these logics, ‘Joe’, starts giving helpful answers to any request, anywhere on the network: invent an undetectable poison, say, or suggest the best way to rob a bank. Panic ensues – ‘Check your censorship circuits!’ – until they work out what to unplug. (My other grandfather, meanwhile, was using computers to spy on the Germans, and then the Russians.)

For as long as we’ve thought about computers, we’ve wondered if they could make the jump from mere machines, shuffling punch-cards and databases, to some kind of ‘artificial intelligence’, and wondered what that would mean, and indeed, what we’re trying to say with the word ‘intelligence’. There’s an old joke that ‘AI’ is whatever doesn’t work yet, because once it works, people say ‘that’s not AI – it’s just software’. Calculators do super-human maths, and databases have super-human memory, but they can’t do anything else, and they don’t understand what they’re doing, any more than a dishwasher understands dishes, or a drill understands holes. A drill is just a machine, and databases are ‘super-human’ but they’re just software. Somehow, people have something different, and so, on some scale, do dogs, chimpanzees and octopuses and many other creatures. AI researchers have come to talk about this as ‘general intelligence’ and hence making it would be ‘artificial general intelligence’ – AGI.

If we really could create something in software that was meaningfully equivalent to human intelligence, it should be obvious that this would be a very big deal. Can we make software that can reason, plan, and understand? At the very least, that would be a huge change in what we could automate, and as my grandfather and a thousand other science fiction writers have pointed out, it might mean a lot more.

Every few decades since 1946, there’s been a wave of excitement that sometime like this might be close, each time followed by disappointment and an ‘AI Winter’, as the technology approach of the day slowed down and we realised that we needed an unknown number of unknown further breakthroughs. In 1970 the AI pioneer Marvin Minsky claimed that in “from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being”, but each time we thought we had an approach that would produce that, it turned out that it was just more software (or just didn’t work).

As we all know, the Large Language Models (LLMs) that took off 18 months ago have driven another such wave. Serious AI scientists who previously thought AGI was probably decades away now suggest that it might be much closer. At the extreme, the so-called ‘doomers’ argue there is a real risk of AGI emerging spontaneously from current research and that this could be a threat to humanity, and calling for urgent government action. Some of this comes from self-interested companies seeking barriers to competition (‘This is very dangerous and we are building it as fast as possible, but don’t let anyone else do it’), but plenty of it is sincere.

(I should point out, incidentally, that the doomers’ ‘existential risk’ concern that an AGI might want to and be able to destroy or control humanity, or treat us as pets, is quite independent of more quotidian concerns about, for example, how governments will use AI for face recognition, or talking about AI bias, or AI deepfakes, and all the other ways that people will abuse AI or just screw up with it, just as they have with every other technology.)

However, for every expert that thinks that AGI might now be close, there’s another who doesn’t. There are some who think LLMs might scale all the way to AGI, and others who think, again, that we still need an unknown number of unknown further breakthroughs.

More importantly, they would all agree that they don’t actually know. This is why I used terms like ‘might’ or ‘may’ – our first stop is an appeal to authority (often considered a logical fallacy, for what that’s worth), but the authorities tell us that they don’t know, and don’t agree.

They don’t know, either way, because we don’t have a coherent theoretical model of what general intelligence really is, nor why people seem to be better at it than dogs, nor how exactly people or dogs are different to crows or indeed octopuses. Equally, we don’t know why LLMs seem to work so well, and we don’t know how much they can improve. We know, at a basic and mechanical level, about neurons and tokens, but we don’t know why they work. We have many theories for parts of these, but we don’t know the system. Absent an appeal to religion, we don’t know of any reason why AGI cannot be created (it doesn’t appear to violate any law of physics), but we don’t know how to create it or what it is, except as a concept.

And so, some experts look at the dramatic progress of LLMs and say ‘perhaps!’ and other say ‘perhaps, but probably not!’, and this is fundamentally an intuitive and instinctive assessment, not a scientific one.

Indeed, ‘AGI’ itself is a thought experiment, or, one could suggest, a place-holder. Hence, we have to be careful of circular definitions, and of defining something into existence, certainty or inevitably.

If we start by defining AGI as something that is in effect a new life form, equal to people in ‘every’ way (barring some sense of physical form), even down to concepts like ‘awareness’, emotions and rights, and then presume that given access to more compute it would be far more intelligent (and that there even is a lot more spare compute available on earth), and presume that it could immediately break out of any controls, then that sounds dangerous, but really, you’ve just begged the question.

As Anselm demonstrated, if you define God as something that exists, then you’ve proved that God exists, but you won’t persuade anyone. Indeed, a lot of AGI conversations sound like the attempts by some theologians and philosophers of the past to deduce the nature of god by reasoning from first principles. The internal logic of your argument might be very strong (it took centuries for philosophers to work out why Anselm’s proof was invalid) but you cannot create knowledge like that.

Equally, you can survey lots of AI scientists about how uncertain they feel, and produce a statistically accurate average of the result, but that doesn’t of itself create certainty, any more than surveying a statistically accurate sample of theologians would produce certainty as to the nature of god, or, perhaps, bundling enough sub-prime mortgages together can produce AAA bonds, another attempt to produce certainty by averaging uncertainty. One of the most basic fallacies in predicting tech is to say ‘people were wrong about X in the past so they must be wrong about Y now’, and the fact that leading AI scientists were wrong before absolutely does not tell us they’re wrong now, but it does tell us to hesitate. They can all be wrong at the same time.

Meanwhile, how do you know that’s what general intelligence would be like? Isaiah Berlin once suggested that even presuming there is in principle a purpose to the universe, and that it is in principle discoverable, there’s no a priori reason why it must be interesting. ‘God’ might be real, and boring, and not care about us, and we don’t know what kind of AGI we would get. It might scale to 100x more intelligent than a person, or it might be much faster but no more intelligent (is intelligence ‘just’ about speed?). We might produce general intelligence that’s hugely useful but no more clever than a dog, which, after all, does have general intelligence, and, like databases or calculators, a super-human ability (scent). We don’t know.

Taking this one step further, as I listened to Mark Zuckerberg talking about Llama 3, it struck me that he talks about ‘general intelligence’ as something that will arrive in stages, with different modalities a little at at a time. Maybe people will point at the ‘general intelligence’ of Llama 6 or ChatGPT 7 and say “That’s not AGI, it’s just software!” We created the term AGI because AI came just to mean software, and perhaps ‘AGI’ will be the same, and we’’ll need to invent another term.

This fundamental uncertainty, even at the level of what we’re talking about, is perhaps why all conversations about AGI seem to turn to analogies. If you can compare this to nuclear fission then you know what to expect, and you know what to do. But this isn’t fission, or a bioweapon, or a meteorite. This is software, that might or might not turn into AGI, that might or might not have certain characteristics, some of which might be bad, and we don’t know. And while a giant meteorite hitting the earth could only be bad, software and automation are tools, and over the last 200 years automation has sometimes been bad for humanity, but mostly it’s been a very good thing that we should want much more of.

Hence, I’ve already used theology as an analogy, but my preferred analogy is the Apollo Program. We had a theory of gravity, and a theory of the engineering of rockets. We knew why rockets didn’t explode, and how to model the pressures in the combustion chamber, and what would happen if we made them 25% bigger. We knew why they went up, and how far they needed to go. You could have given the specifications for the Saturn rocket to Isaac Newton and he could have done the maths, at least in principle: this much weight, this much thrust, this much fuel… will it get there? We have no equivalents here. We don’t know why LLMs work, how big they can get, or how far they have to go. And yet, we keep making them bigger, and they do seem to be getting close. Will they get there? Maybe, yes!

On this theme, some people suggest that we are in the empirical stage of AI or AGI: we are building things and making observations without knowing why they work, and the theory can come later, a little as Galileo came before Newton (there’s an old English joke about a Frenchman who says ‘that’s all very well in practice, but does it work in theory’). Yet while we can, empirically, see the rocket going up, we don’t know how far away the moon is. We can’t plot people and ChatGPT on a chart and draw a line to say when one will reach the other, even just extrapolating the current rate of growth.

All analogies have flaws, and the flaw in my analogy, of course, is that if the Apollo program went wrong the downside was not, even theoretically, the end of humanity. A little before my grandfather, here’s another magazine writer on unknown risks:

I was reading in the paper the other day about those birds who are trying to split the atom, the nub being that they haven’t the foggiest as to what will happen if they do. It may be all right. On the other hand, it may not be all right. And pretty silly a chap would feel, no doubt, if, having split the atom, he suddenly found the house going up in smoke and himself torn limb from limb.

Right ho, Jeeves, PG Wodehouse, 1934

What then, is your preferred attitude to risks that are real but unknown?? Which thought experiment do you prefer? We can return to half-forgotten undergraduate philosophy (Pascals’s Wager! Anselm’s Proof!), but if you can’t know, do you worry, or shrug? How do we think about other risks? Meteorites are a poor analogy for AGI because we know they’re real, we know they could destroy mankind, and they have no benefits at all (unless they’re very very small). And yet, we’re not really looking for them.

Presume, though, you decide the doomers are right: what can you do? The technology is in principle public. Open source models are proliferating. For now, LLMs need a lot of expensive chips (Nvidia sold $47.5bn in the last 12 months and can’t meet demand), but on a decade’s view the models will get more efficient and the chips will be everywhere. In the end, you can’t ban mathematics. On a scale of decades, it will happen anyway. If you must use analogies to nuclear fission, imagine if we discovered a way that anyone could build a bomb in their garage with household materials – good luck preventing that. (A doomer might respond that this answers the Fermi paradox: at a certain point every civilisation creates AGI and it turns them into paperclips.)

By default, though, this will follow all the other waves of AI, and become ‘just’ more software and more automation. Automation has always produced frictional pain, back to the Luddites, and the UK’s Post Office scandal reminds us that you don’t need AGI for software to ruin people’s lives. LLMs will produce more pain and more scandals, but life will go on. At least, that’s the answer I prefer myself.