Carrots. Puffed sleeves. Scrapes. Liniment. Kindred spirits. Bosom friends.

To some readers, this collection of words will read like a haiku gone wrong. But to a certain contingent of old-fashioned bookworms, it’s a trail of bread crumbs leading to a redheaded Canadian orphan named Anne Shirley. She blazed into the world in 1908 as an unsinkable 11-year-old in Lucy Maud Montgomery’s debut novel, “Anne of Green Gables,” then grew up on the pages of subsequent books. She isn’t related to Annie, that other ginger who belted out “Tomorrow,” but the two share an optimism and magnetism that have exerted their pull on generations of devotees.

Since its publication, “Anne of Green Gables” has sold around 50 million copies. It’s been translated into 36 languages; adapted for stage, television and film; and has inspired spinoffs, knockoffs, fan fiction and many a pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island, where visitors can tour the Anne of Green Gables Museum, Green Gables Heritage Place and Montgomery’s birthplace.

Further afield, “Anne Fans” attend conferences, chat on Reddit threads and organize dinner parties and book clubs, all with an Anne theme. They cultivate an encyclopedic knowledge of trivia, from the names of her childhood nemesis (Josie Pye) and her oldest son’s wife (Faith) to the cause of her broken ankle (falling off a roof). Among this sweetly nostalgic crew, Anne’s husband is shorthand for a perfect match — as in, “I found my Gilbert.”

But ask the average Anne Fan about Emily Byrd Starr and you’re likely to be met with confusion: Are you sure you’re not thinking of Emily Harrison from “Anne of Avonlea”? The one who left her husband because of his rude parrot?

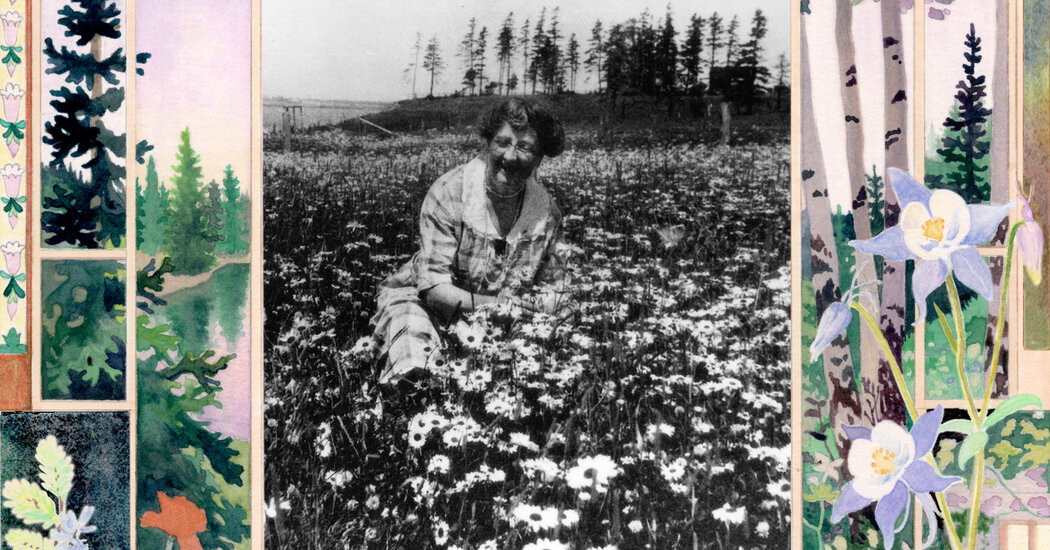

To be fair, this Emily hails from a different Montgomery series, one that launched in 1923 with “Emily of New Moon.” She, too, is a literary-minded orphan growing up on Prince Edward Island. Her name might not come up on a carriage tour of Montgomery’s world, but according to the author’s granddaughter, she has more in common with her creator than Anne does.

“‘Emily of New Moon’ was my grandmother’s favorite book because it’s autobiographical,” Kate Macdonald Butler said. “There’s a lot of her in that story.”

As president of Heirs of L.M. Montgomery Inc., Butler is accustomed to frequent queries from strangers. But, she said, “You’re the first person who’s called me about ‘Emily of New Moon’ being 100 years old this year.”

The occasion raises some questions. Why is Emily forever in Anne’s shadow? Is it possible that her story holds up even better than Anne’s after all these years — in other words, should BookTok get behind her?

Emily certainly has the hallmarks of a viral sensation: passion, courage, intriguing “violet” eyes, a tragic back story. When her father dies of consumption, she’s sent to New Moon to live with her mother’s sisters, Elizabeth (mean) and Laura (meek). At her new school, she gets hoodwinked, then dropped, by a social climber; befriends two solid individuals with complicated family dynamics; visits another aunt (manipulative) and solves a mystery.

While Anne’s caretakers learn to appreciate her creative streak, Emily is actively thwarted by Aunt Elizabeth. Both girls run into challenges in their new communities, but Emily’s are ratcheted up a notch: Her best friend is temperamental. Her teacher is cruel. Her first stirrings of romance are complicated by the attention of an older man whose behavior sets off alarm bells. (CoHo fans, do you read me?)

Emily is a scrappier, more complex character than Anne, with a wicked temper and a refreshing candor. When classmates ridicule her apron, her bonnet, her ears and, finally, her uncle, she threatens them with the evil eye, then defuses the situation by asking, point blank, “Why don’t you like me?” She refuses to bend to her aunts’ rules even when it means burning her writing to avoid their scrutiny. When she experiences “the flash” — that rare, inspiring moment when she feels she can peer into another world — she pays attention.

“She could never recall it — never summon it — never pretend it,” Montgomery writes, “but the wonder of it stayed with her for days.”

“Anne has a certain shine we’d all like to bask in,” said Elizabeth Rollins Epperly, founder of the L.M. Montgomery Institute at the University of Prince Edward Island and author of several books about Montgomery’s work. “With Emily, we have to swallow some of the bitterness that she does as well. We get angry on her behalf. We identify with her, but we also identify that life is not going to be accommodating, rosy and kind.”

Perhaps Natasha Lyonne’s character in “Russian Doll” summed it up when she said, “Everybody loves Anne. But I like Emily. She’s dark.”

Montgomery started writing about Emily in 1921, in the aftermath of World War I. The influenza pandemic had just swept through Canada, striking Montgomery and claiming her cousin and close friend, Frederica Campbell MacFarlane, with whom she had teamed up to care for family on Prince Edward Island. Steeped in this trauma, Montgomery needed a break from sunny Anne. She channeled her heartbreak into mercurial Emily.

In a journal entry dated Feb. 15, 1922, Montgomery described “Emily of New Moon” as “the best book I have ever written.” She wrote, “I have had more intense pleasure in writing it than any of the others — not even excepting Green Gables. I have lived it, and I hated to pen the last line and write finis.”

Then Montgomery added, “Of course, I’ll have to write several sequels but they will be more or less hackwork I fear. They cannot be to me what this book has been.”

“Emily Climbs” and “Emily’s Quest” came out in 1925 and 1927. They’re as vibrant as their progenitor, with the added bonuses of Emily’s career success and an exciting love triangle.

Anne’s and Emily’s paths diverged from the start. Not only did the books have contrasting worldviews, they also had different publishers and marketing strategies.

“Anne of Green Gables” was published by L.C. Page of Boston, with whom Montgomery had a falling-out over what Irene Gammel, the executive director of the Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University, described in an interview as “exploitative terms.” The Page first edition had a cosmopolitan look, featuring a sophisticated, Gibson girl-esque Anne on the cover. From the start, the book was destined to have crossover appeal.

Fifteen years later, Frederick A. Stokes, a Canadian publisher, launched “Emily of New Moon” into a darker, more pessimistic time, featuring a folksy, floral look and a cover picture of a young girl in a rural setting; as a result, older readers might have steered clear.

The book had a positive reception but a lukewarm review in The New York Times. “Miss Montgomery has created a charmingly winsome character in little Emily Starr,” wrote an unnamed reviewer. He — just a hunch — continued, “There is little originality in either her plot or her characters.”

Even hot off the press, Emily couldn’t keep up with Anne, which bothered Montgomery. “She complained about that. She was ready to dive into a different kind of writing,” said Gammel, who wrote “Looking for Anne of Green Gables.” Eventually, driven by popular demand, Montgomery returned to her original heroine, filling in some of the gaps in her story with “Anne of Windy Poplars” and “Anne of Ingleside.”

As Gammel pointed out, when you look at “Rilla of Ingleside,” one of the novels about Anne’s adult life, you find her “relegated to the sidelines.” Her daughter carries the story: “All that imagination and spunk she had early on, and she just became the model housewife.”

Anne does what was expected of women of her day; Emily becomes a published author.

At the end of “Emily of New Moon,” she opens a new notebook and scribbles a promise: “I am going to write a diary, that it may be published when I die.”

On April 24, 1942, only a few hours after sending one final Anne manuscript to her publisher, Montgomery died of a drug overdose. She was 67 years old.

In a 2008 story in The Globe and Mail, Butler revealed that her grandmother had suffered from depression and taken her own life. “People were shocked,” she said. “I’ve never regretted publishing that information. I hope somebody read it and thought, Lucy Maud Montgomery was suffering and so am I.”

Emily wasn’t mentioned in Montgomery’s Times obituary; the focus was on Anne, “the sweetest creation of child life yet written,” according to Mark Twain.

Today, a first edition of “Anne of Green Gables” sells for $22,000, while a first edition of “Emily of New Moon” is available for less than $200.

This much is clear: Emily Byrd Starr was forged in a time of uncertainty, one similar to our own. Like Montgomery, she bushwhacked her way through loneliness on a path made of paper, ink and words. At 100 years old, she deserves a spotlight of her own.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for a list of additional resources.