What questions about the Universe keep you awake at night? Do you ever think about how the Universe began, how it will end, whether there was anything before this Universe?

Questions abound in science, physics and astronomy. That’s what keeps science so dynamic and interesting: there’s always something new to discover, even if it’s simply a question that we never thought to ask before.

The Universe is a strange place, filled with wonder and beauty, but also a plethora of unsolved mysteries and unanswered questions.

Most of us can understand the notion of stars and planets, planetary systems and distant moons, swirling galaxies filled with thick stardust and glowing nebulae.

Read more:

But where things get tricky are the more abstract questions relating to space and time.

When did time begin? What came before that? Does the Universe go on forever? If so, how can this be possible?

Faced with some of these astrophysical uncertainties and cosmological conundrums, we asked radio astronomer Dr Alastair Gunn to share some of his knowledge and expertise, to help us get a better grasp on some of the biggest unanswered questions about the space and Universe.

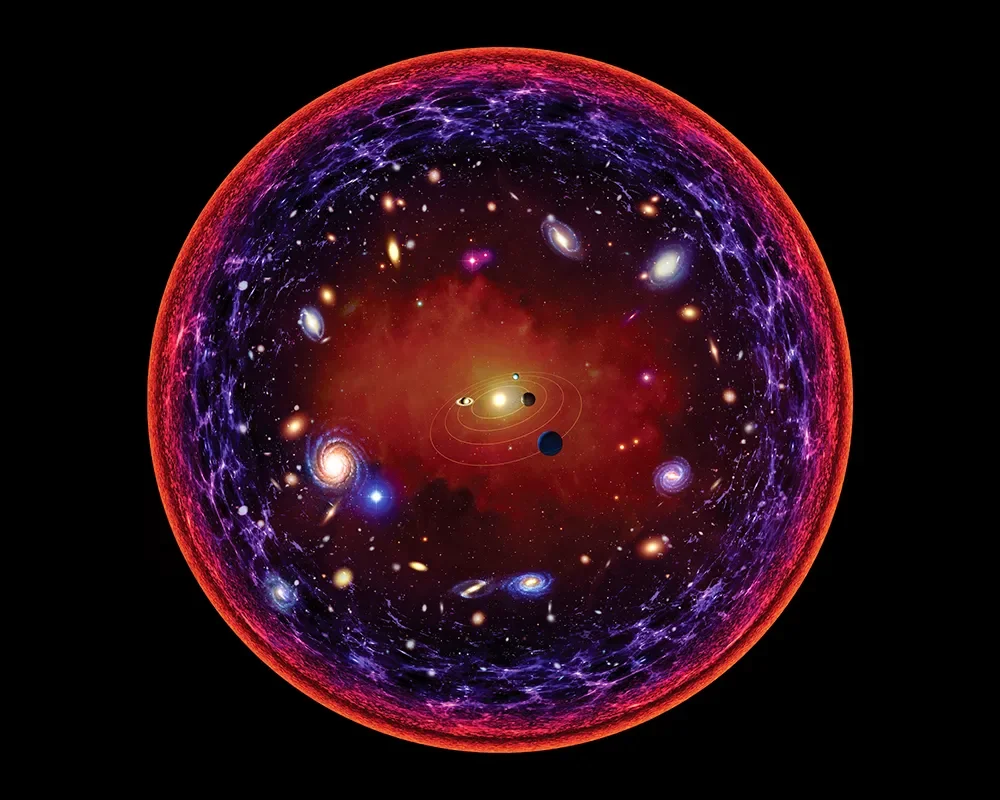

Is the Universe infinite?

Astronomers have found that the Universe is 13.8 billion years old.

That’s quite old, but some very distant parts of the Universe may simply be too far away for light to have travelled to us during that time.

This defines what astronomers call the ‘observable Universe’, that is, the parts of the Universe we can actually see. We can never observe anything beyond this finite limit.

However, the question whether the wider Universe is finite or infinite depends on its geometry.

Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity allows three shapes, or geometries, for the Universe: ‘flat’, ‘closed’ or ‘open’.

It is difficult to envisage these but they can be compared to a sheet of paper (flat), a sphere (closed) or a saddle (open). Which one it is depends on its total density and its rate of expansion.

Over the past few decades astronomers have measured these quantities and found that the Universe is almost certainly ‘flat’.

This may mean the Universe is infinite, but it may also mean its geometry is just very complex, though still finite.

Other studies have recently suggested the Universe is ‘closed’, and therefore finite. So, frustratingly, astronomers are currently unable to say whether the Universe is infinite or not.

Could there be an edge of the Universe?

Does the Universe have an edge? This is one of those questions about the Universe that seems so mind boggling it might be difficult to know where to start.

So let’s concentrate first on what we do know.

The Universe has been expanding for the last 13.8 billion years. So, the regions of space that lie at the edge of the observable Universe are now much further away than when their light was emitted.

This means the edge of the observable Universe lies about 46 billion lightyears away in every direction.

The observable Universe is thus a sphere with a diameter of about 92 billion lightyears and a volume of about 410 nonillion (410 thousand billion billion billion) cubic light-years!

However, there is no reason to suspect this limit is an actual edge to the Universe or that what lies beyond this, if it exists, has an edge at all.

Even if the Universe is finite, it does not have to have an edge, in the same way that the surface of the Earth is finite but unbounded.

It all depends on the actual geometry of the wider Universe, and this we currently don’t know for sure.

If the Universe is infinite, how can it be expanding?

If the Universe is infinite then it can simply keep expanding without getting any bigger (since you can’t get bigger than infinity).

That might seem a facetious answer. But, when astronomers refer to the expansion of the Universe they are referring to the abstract concept of ‘empty space’.

As the Universe expands, space itself inflates, creating extra distance between objects.

There is no conundrum in this, whether or not the Universe is infinite.

What is the Universe made of?

Observations have shown that ordinary matter in the Universe accounts for only 4.9% of its content.

26.8% of it is due to dark matter, a form of matter not directly visible.

The remaining 68.3% is due to dark energy, a mysterious energy field causing the expansion of the Universe to accelerate.

The exact nature of dark matter and dark energy are currently not fully understood.

Of the 4.9% of the Universe we do understand, about 74% is hydrogen, 24% helium and the rest is heavier elements.

Are the laws of physics the same everywhere?

One of the fundamental axioms of physics is that the laws that govern the Universe are the same everywhere and have remained so throughout time.

However, there is no convincing physical reason why this should be the case.

To test this, scientists have attempted to measure small differences in the constants that govern the forces of nature.

Most have demonstrated, with a high degree of accuracy, that the laws of nature are the same everywhere.

However, some studies have hinted that one constant, the ‘fine structure constant’ — the constant which determines how electric charges interact — might have been different in the past.

The result, which may not be statistically significant, is controversial, and most scientists would agree is currently unproven.

Do parallel universes exist?

When it comes to questions about the Universe, this may be one we will never be able to answer.

But physicists believe there are various ways that ‘alternative’ or ‘parallel’ universes could be created.

Some involve the splitting of space due to unequal inflation just before the Big Bang.

Others are based on the ‘many-worlds’ interpretation of quantum physics, on the string theory of elementary particles, the fact that the constants of nature are so finely balanced, or simply on the assumption that the Universe is infinite.

A few studies have even hinted at possible detections of parallel universes: one from variations of the ‘cosmic microwave background’, and another in the detection of neutrinos in Antarctica.

But both these were later shown to be erroneous. Some scientists reject parallel universes simply on logical grounds or because the idea is unfalsifiable.

So, parallel universes may or may not exist.

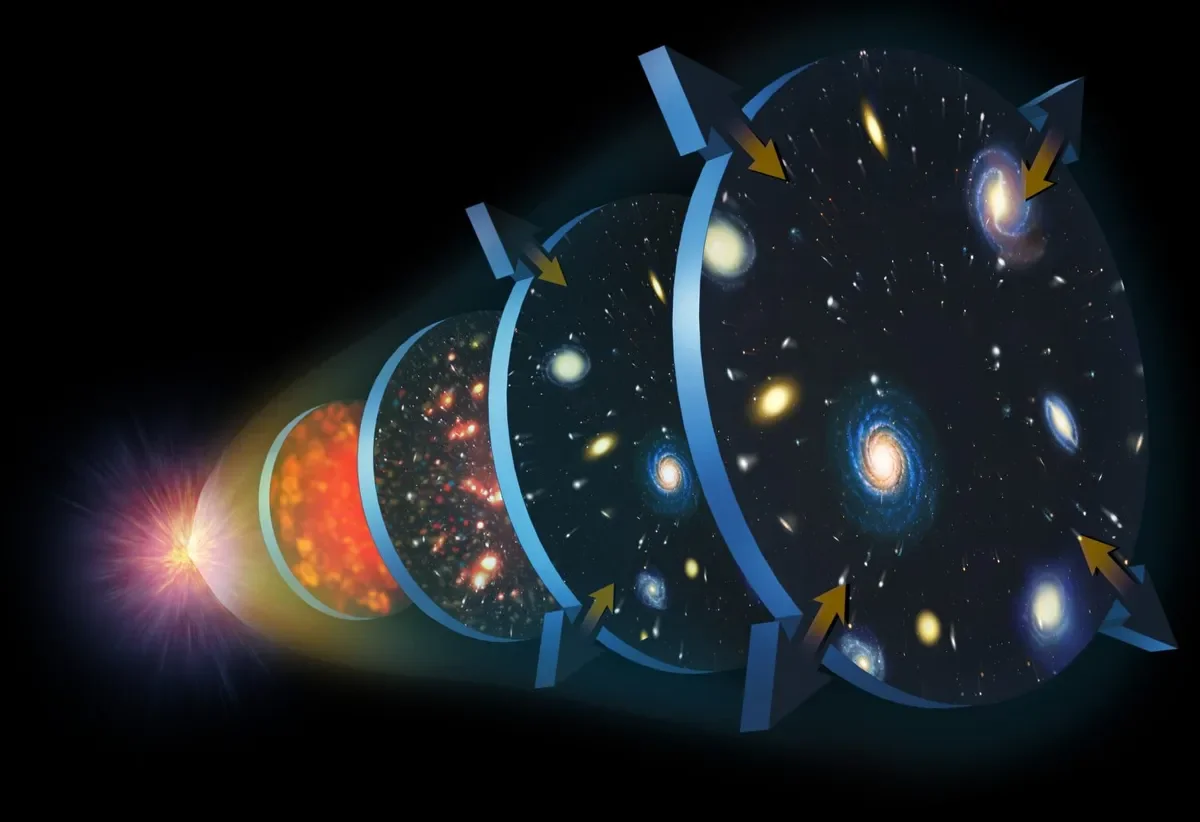

What came before the Universe?

Could there have been a Universe before the Big Bang?

A common misconception is that both space and time began with the Big Bang. There is, in fact, no physical reason to suppose this was the case.

Unfortunately, modern physics breaks down completely at the moment of ‘creation’ — because of those pesky mathematical ‘singularities’.

So, it is difficult to say anything certain about what might have happened or existed before the present Universe came into being.

However, this hasn’t stopped some scientists speculating.

It may be that nothing at all existed before the Big Bang — no space and no time, not even a convenient void.

Perhaps previous universes existed, or merely an energy field, or different versions of our own Universe, or a plethora of universes with different physical laws.

Although such theories are an important part of modern cosmology, just like parallel universes, observational evidence for them is extremely hard (if not impossible) to come by.

So, again, astronomers can’t really answer this question.

Will the Universe ever end?

“Will the Universe end?” is one of the biggest, and perhaps most important, questions about the Universe.

Whether the Universe will exist forever or in some way ‘end’ depends on its rate of expansion, the average density of matter, and the fractions of matter, dark matter and dark energy it contains.

If the Universe’s geometry is ‘closed’ then gravity eventually stops the expansion, leading to a ‘Big Crunch’ in which it collapses back to an infinitely dense point similar to that from which it sprang.

However, if it is ‘flat’ or ‘open’ (and it appears to be flat), it will continue to expand forever.

It will still ‘die’, however, in the sense that matter and energy will eventually reach equilibrium, becoming evenly spread throughout space and resulting in a sterile Universe where nothing ever happens.

This is known as the ‘Big Freeze’.

For more musings on the possible ends of the Universe, read our interview with Dr Katie Mack.

Do you have any questions about the Universe? Email us at contactus@skyatnightmagazine and we may answer your question in a future issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.