<div class="article-block article-text" data-behavior="newsletter_promo dfp_article_rendering" data-dfp-adword="Advertisement" data-newsletterpromo_article-text="

Sign up for Scientific American’s free newsletters.

” data-newsletterpromo_article-image=”https://static.scientificamerican.com/sciam/cache/file/4641809D-B8F1-41A3-9E5A87C21ADB2FD8_source.png” data-newsletterpromo_article-button-text=”Sign Up” data-newsletterpromo_article-button-link=”https://www.scientificamerican.com/page/newsletter-sign-up/?origincode=2018_sciam_ArticlePromo_NewsletterSignUp” name=”articleBody” itemprop=”articleBody”>

The conversation around diabetes has predominantly revolved around an energy surplus: if a person takes in more energy than they expend, over time, they may become obese and develop its associated metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes. Most treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration aim to limit calorie intake or suppress the appetite. Researchers have, however, rarely discussed the effect of malnutrition on insulin.

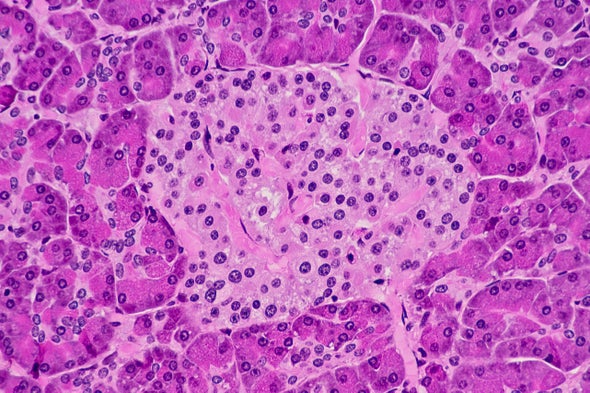

In recent decades, a more nuanced picture of diabetes has emerged that shows the quality and composition of diet matter, perhaps as much as calorie intake. For example, studies have shown that choosing whole grains over refined grains decreases a person’s risk of type 2 diabetes. Numerous rodent studies have shown that protein deficiency early in life results in a problem with insulin secretion, linked to the smaller volume of pancreatic beta cells that produce the hormone. Interestingly, nutrient supplementation alleviates this problem. But until now this problem had not been thoroughly investigated in humans.

A new study published in Diabetes Care finds that people with a history of malnutrition exhibit a distinct type of diabetes characterized by a similar problem with insulin secretion. Men in the study who have a low body mass index (BMI) secrete less insulin than healthy people and people with type 2 diabetes but more insulin than people with type 1 diabetes. They are also less insulin-resistant than people with type 2 diabetes. These findings again suggest that a distinct type of diabetes with a unique metabolic profile is present in the population.

This study is not the first link between malnutrition and diabetes, but as a biochemist and an economist, we believe the results warrant immediate and extensive investigation from scientific community and public health regulatory bodies. In 1985, a World Health Organization study group recognized malnutrition-related diabetes as a distinct clinical class. However, because of a lack of follow-up studies and insufficient evidence, WHO removed this category from its diabetes classification in 1999.

We cannot ignore this call a second time. Around 462 million underweight adults worldwide may have a history of malnourishment, and almost 250 million children under the age of five years are malnourished. If follow-up studies of diverse, heterogeneous populations confirm the existence of malnutrition-related diabetes, global public health organizations must reorient strategies and reconfigure therapies to prevent and help people manage this specific type of diabetes.

Malnutrition-related diabetes would add but another dimension to the global problem of malnutrition, which must be addressed for the sake of human health and well-being as well as the health of local economies.

A lack of access to nutritious food is severe and unfortunately common in developing nations. As but one example, Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen vividly depicted the state of malnutrition among Indian children in their 2013 book An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions. Drèze and Sen observed that 43 percent of Indian children are undernourished by weight and 48 percent by height before they reach five years of age. Among preschool-aged children, 74 percent are anemic, and 62 percent are deficient in vitamin A. And 31 percent of school-aged children are deficient in iodine.

Even in some relatively affluent nations, demographics—more so than individual choices—heavily influence whether a person has access to enough high-quality food and thus their metabolic health. Fast-food restaurants are five times as common in low-income areas of the U.K. as they are in affluent areas, and children from these areas are more than twice as likely to be overweight. On the other hand, countries such as Sweden, Denmark and South Korea that have robust school meal programs have low childhood obesity rates. And citizens of developed nations are not immune to the dangers of diabetes: in the U.S., diabetic people who have encountered food shortages are 2.3 times as likely to have experienced severe hypoglycemia, according to a study presented at the 2023 European Association for the Study of Diabetes annual meeting. A lack of safe and affordable insulin compounds this issue.

The prevalence of obesity and diabetes in any country reflects the extent to which its citizens must compensate for a lack of access to proper nutrition by eating low-quality, unhealthy and inadequate food. Neglect of public health concerns; the market’s hunger for profit from cheap, ultraprocessed food; and unethical marketing that targets children all contribute to malnutrition. We are facing a double-edged sword where both excessive energy surplus and energy deficiency lead to different forms of diabetes. Countries that blindly neglect children’s health and nutrition risk becoming diabetic hotspots in the future. And obesity and type 2 diabetes are major risk factors for other diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and certain cancers.

Governments can address the magnitude of malnutrition afflicting children and adolescents worldwide with a well-funded, nutritionist-monitored midday meal provision for students, as well as with food subsidies that ensure adequate food security for all, especially low-income households. For interventions to be effective, governments will need to address the socioeconomic dimensions underpinning both malnutrition and obesity. Fighting obesity and malnutrition-related diabetes through such a public food program strategy would be an investment that countries like India should pursue to reduce health care costs down the line and contribute to the health of future generations.

Civil society and governments must prioritize nutrition more than ever, given the increasingly obvious health risks of malnutrition. Doing so is not only a smart investment in public health but a moral obligation. We must enact these food programs before the beta cells of millions more people stop producing adequate insulin because of nutrient deficiency. Not to do so would be to knowingly neglect public health and would be a moral failure of our time.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

![]() Rights & Permissions

Rights & Permissions