Image: Mark Thomas

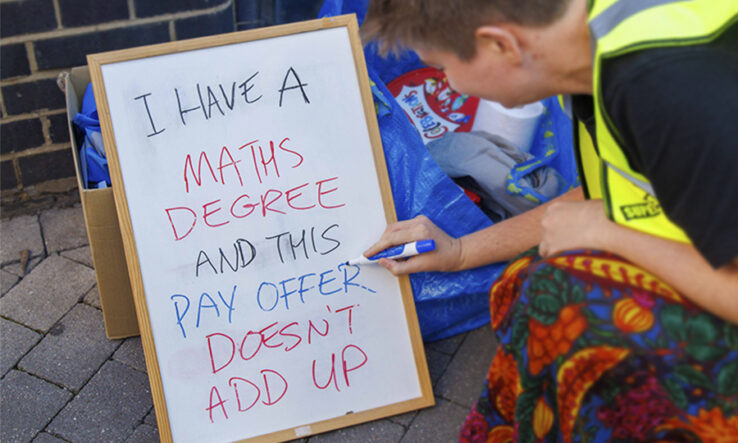

When salaries don’t keep pace with inflation, a passion for science doesn’t pay the bills

On Thursday 20 June, the science journal Nature published its 8,017th issue. Like its 8,016 predecessors, this latest issue contained cutting-edge papers from across the disciplines of science. But last Thursday was historic for the journal not because of any paradigm-shattering discovery but because it marked the start of sustained industrial action by its London-based staff.

Negotiations over pay between members of the National Union of Journalists and Nature’s UK parent company Springer Nature broke down in April after seven months.

The NUJ, which represents writers, editors and art and production staff who work on Nature and the broader stable of Nature-branded journals, balloted its members in May. At 93 per cent, support for action was overwhelming.

While the staff involved feel trepidation about the path they are embarking on, they remain hopeful that the company will return to the table quickly to resolve the dispute.

Last resort

Industrial action is a last resort and in many ways an admission of failure. It signals the breakdown of what should be a healthy and constructive relationship between employer and employees.

It puts huge strain on employees and threatens to disrupt the business. It is divisive and damaging. So why would a team of essentially academic workers choose such a path? The short answer is that it was forced upon us.

Nature’s mission statement sets out its ambition for the results of science to be “rapidly disseminated to the public throughout the world, in a fashion that conveys their significance for knowledge, culture and daily life”. For the editorial and production teams at Nature and its sister titles, this mission is as much a vocation as a job.

Day-to-day duties alone often demand 10-hour days and six-day weeks. On top of this, editors do significant outreach—spending their evenings at events or online conferences, giving talks, helping to negotiate standards and, as science becomes ever more interdisciplinary, helping researchers find a common language. It’s obvious that a lot of this goes beyond their basic contracts.

We do these things because we are dedicated to science, inspired by the progress of knowledge and driven to help disseminate the results for the greater good. The reward is not solely financial—it is the connection to the acquisition of knowledge and the societal benefits that this yields.

But passion doesn’t pay the bills. The surge in the cost of living has made salaries that were barely adequate wholly insufficient.

Falling UK inflation hides the lived reality: the cost of everyday necessities has risen dramatically. Things that became unaffordable last year are still getting more expensive, just a bit more slowly.

Staff report mortgage or rent rises in excess of 20 per cent. Others have seen childcare costs rise by nearly 30 per cent. Weekly shopping bills are up by 15 to 20 per cent.

Many live from paycheque to paycheque. As one employee puts it: “I have made cuts that have helped me get by—I no longer have a car or book holidays that require paying for accommodation. I need dental work but I can’t afford it, so I have asked if it will be safe to wait a few years. I am hoping to take on extra work outside of my full-time job to pay for these dentist costs. I work long hours in a complex field and am highly qualified, and yet I can’t make ends meet.”

Erosion of expertise

Rising costs have also affected the company, and everyone recognises that a for-profit organisation must make a sensible profit. But Springer Nature’s balance sheet is healthy; the same cannot be said for the staff’s finances.

Unfortunately, only a subset of Springer Nature’s UK workforce has been granted union recognition—and only after an appeal to the Central Arbitration Committee—so employees outside the defined bargaining unit will not benefit from any agreement resulting from the current action. This is something we regret; ideally, we would negotiate improvements for everyone.

Earlier this year, James Butcher, a former vice-president at Springer Nature and now a freelance consultant, argued that in shifting to a more technological focus, scholarly publishers are starting to undervalue editorial expertise. Such expertise is a scholarly journal’s bedrock.

But watching their pay shrink in real terms year after year, NUJ members at the Nature titles feel that bedrock is being wilfully eroded. We didn’t look for this fight. We don’t want this fight. But we cannot afford to abandon this fight.

The authors are members of staff at Springer Nature in London

This article also appeared in Research Fortnight