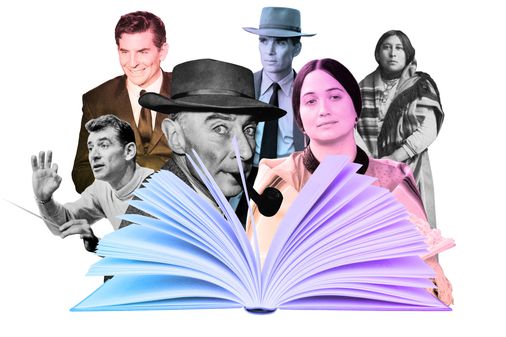

Every day is yesterday — pop culturally, at least. Many of this year’s buzzy Oscar movies are biopics or historical narratives: “Oppenheimer,” “Maestro,” and “Killers of the Flower Moon,” to name three. The same approaches dominate the smaller screen. “The fall TV of 2023,” Kathryn VanArendonk recently noted in Vulture, “has an allergy to modern life.”

It’s easy to see why this trend works for networks and studios. (Like a superhero, a historical figure such as Napoleon arrives with brand awareness and a pre-approved plot.) But does it work for creators and consumers?

In a fascinating new book, “Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon,” Alexander Manshel considers this question carefully. An English professor, he zooms in on literary fiction and finds something surprising: Over the last few decades, contemporary novels have become radically less contemporary. More and more plots now occur in the past, retelling famous events or exploring historical settings and themes, just like in so many movies and shows.

Through a mix of close readings and clever statistics, Manshel shows how recent this revolution is — and also how widespread. His research may also leave readers wondering whether, at this point, it’s a revolution that’s narrowing literature and perhaps even the literary imagination.

Incentives for writing about history

Many of America’s important early novels were historical. (See “The Last of the Mohicans” and “The Scarlet Letter.”) Before long, though, stories set in the past began to seem lowbrow, even pulpy. It was fine for bestsellers, but authors who sought literary prestige wrote about contemporary settings and concerns. “The ‘historical’ novel,” as Henry James put it, is “condemned . . . to a fatal cheapness.”

According to Manshel, this started to flip in the 1980s. He defines historical fiction broadly — not just as narratives that reimagine notable people or events, like Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall,” but as any narrative that takes place in a historical moment instead of our own. The thing that makes science fiction “science fiction” isn’t its characters or style but its setting, say, on some faraway planet or in a speculative future. The thing that makes historical fiction “historical fiction” is its setting in the past.

Historical novels, Manshel argues, have now become “contemporary literature’s most prestigious and politically potent genre.” This is probably true in many countries — certainly, it’s true in Mantel’s Britain — but in America, the best place to see it is by tracking three major literary awards: the Pulitzer Prizes, the National Book Awards, and the National Book Critics Circle Awards. Manshel crunched decades’ worth of shortlists and sorted the nominees into historical fiction and contemporary fiction.

The trends are striking. Between 1950 and 1979, about half of the shortlisted novels met Manshel’s definition of historical fiction. In the 1980s, though, that number jumped to 67 percent, and it’s only climbed higher since. Between 2000 and 2010, 89 of the 111 shortlisted novels were historical fiction — an unprecedented 80 percent. It’s a startling inversion: While most bestsellers are now set in the present (think “Beach Read” author Emily Henry), literary fiction has pivoted to the past (think Colson Whitehead). As Manshel puts it, “Historical fiction now stands at the very center of the American literary canon.”

This shift shows up in other literary institutions, including the distinguished grants that fund writers and the syllabuses that enshrine their most durable books. Manshel analyzed the contents of more than 300,000 literature courses and found that, today, 14 of the 20 most taught post-1945 novels featured plots set in the past. Professors now point not to John Updike or Joyce Carol Oates but to Leslie Marmon Silko and Tim O’Brien, whose novels “Ceremony” and “The Things They Carried” sit comfortably in the campus top 20.

Manshel also explores why this shift happened.

Part of the reason is that novelists have joined journalists and historians in capturing a darker, fuller version of America’s past — and in showing how that past continues to haunt the present. Part of the reason is artists chose to engage with great art. Manshel points to Toni Morrison’s monumental “Beloved,” still the most assigned recent novel in American universities and a revered influence for younger writers like Whitehead.

But Manshel also brings up another Black novelist: Ralph Ellison, whose “Invisible Man” won the National Book Award in 1953. While “Beloved” focuses on 19th-century America, “Invisible Man” offers a plot that was contemporary when it came out. Since the 1980s, America’s literary institutions have elevated the past over the present, the Morrisons over the Ellisons. Manshel’s data make clear that this trend is even more pronounced for writers of color. Between 1980 and 2010, America’s big three awards shortlisted 54 novels by writers of color; 50 of those nominees, or 93 percent, were historical fiction.

Those shortlisted novels represent many wonderful things: the power of Morrison, the choice of authors to explore their own identities and histories, even the publishing industry’s attempts to address its brutal blind spots. (Another English professor, Richard Jean So, has shown that from 1950 to 2000, 97 percent of novels published by Random House were by white authors.)

But those novels also hint at a frustrating irony: While American literature has never been more diverse, its definition of prestige has also never been more homogenized — particularly for writers of color. The most heralded novels about The Way We Live Now tend to come from a Jonathan Franzen, not a Colson Whitehead. “Writers of color have been canonized almost exclusively for providing history and context,” Manshel writes, “while white writers make up the vast majority of those celebrated for writing about the present.”

The stories that don’t get told

Manshel’s case study hints at the complexities behind the culture industry’s historical turn. (It’s hard to think of two groups more different than studio suits in Burbank and literary scholars in Berkeley.) Yet the broader costs of that turn now seem clear. When a genre or style reaches a saturation point, its moves begin to feel tired and predictable instead of surprising or affecting. For a lot of historical art, these moves have become easy to mock: the prestige biopic led by a star who’s unrecognizable thanks to a bad wig and a worse accent, or the dramatic miniseries whose driving idea is that its modern audience is more enlightened than its historical characters.

Of course, the best artists can still make thrilling historical work — and that feels particularly true in the book world. This year has seen a run of wonderful and inventive historical fiction, including Jesmyn Ward’s “Let us Descend,” Zadie Smith’s “The Fraud,” Daniel Mason’s “North Woods,” and Whitehead’s latest, “Crook Manifesto.” But Manshel’s research exposes the inertia and unspoken rules that shape literary institutions. In a chapter on World War II novels, for instance, he notes that America’s big three awards have shortlisted close to a hundred novels about that conflict — except, in this case, 89 percent of those novels have come from white writers, not writers of color. It’s indisputable evidence of a system that constrains its creators, whispering that one kind of author should write about this slice of history while another kind of author should avoid it.

It’s also a reminder that, in 2023, the historical turn limits the options and maybe even the imaginations of American artists. The biggest loss is the books, movies, and TV shows that don’t get made — the missing art that might explore the themes, emotions, and difficulties of the present. After all, the flipside of Manshel’s most shocking statistic — that between 1980 and 2010, 50 of the 54 shortlisted novels by writers of color were historical — is that only four of those celebrated novels focused on contemporary life, four novels in 30 years of culture.

What if the literary world pursued a more radical form of diversity? What if our authors wrote, and what if our institutions supported, more novels that examined our own overwhelming moment?

Craig Fehrman is a journalist and historian. He is at work on a revisionist history of the Lewis and Clark expedition, for Simon & Schuster.