“To the 12,750 people who ordered a single takeaway on Valentine’s Day. You OK, hun?”

Stuck up on London underground trains by Revolut in 2019, the damning question was the fintech’s tongue-in-cheek attempt to show off its close relationship with customers.

The ad sparked a backlash, with many taking to social media to call out not only its patronising, “single-shaming” tone, but the fact that Revolut’s private bank transaction data could be so casually publicised.

The PR disaster serves as a cautionary tale of the sensitivities around customer data in financial services, where trust and privacy are paramount to the client relationship.

Banks and payment companies have amassed a trove of data about clients’ financial behaviour, the rewards of which are too tempting to overlook.

While more conservative banks devote resources to “indirectly monetise” their customers’ information by offering them better-suited offers and products, the boldest disrupters — fintechs such as Revolut, Klarna and PayPal, as well as the US bank Chase — are experimenting with selling anonymised data to advertisers.

Andreas Schwabe, managing director at consultants Alvarez & Marsal, describes the sector as being at at a “critical juncture” with regards to its use of customer data, either for internal or external purposes.

“For banks and payments companies, the question is no longer whether they can leverage their data, but how and when they will seize this opportunity — and who will emerge as the frontrunner in this rapidly evolving landscape,” he says.

So what exactly do banks and payment providers plan to do with your financial data? Is it safe? And is there anything you can do about it?

The value of our financial data has been recognised for decades. “Information about money has become almost as important as money itself,” observed former Citibank chief executive Walter Wriston in 1984. Though his efforts to position the lender as a competitor to data companies such as Bloomberg largely failed, the adage is truer now than ever.

As the use of cash falls, more of our lives are recorded in the form of electronic payments. From friend and business networks to spending on everything from luxury handbags to charitable donations to gambling and pornography sites, much can be revealed about a person from their bank account and transaction history.

The use of personal data is regulated differently across Europe and the US. UK legislation splits data into two categories. Sensitive, or “special category”, data includes information about racial or ethnic origin, genetics, religion, trade union membership, biometrics, health and sexual orientation. The rest is classified as non-sensitive data, which is easier for companies to handle.

Transaction data is not inherently sensitive, but protected characteristics can be gleaned through analysis and enrichment — the process of improving the value of existing data by adding new or missing information.

Karla Prudencio Ruiz, an advocacy officer at the research non-profit group Privacy International, gives the example of a banking customer who pays school fees at a faith school, suggesting their religion; or someone spending regularly at the oncology unit at a hospital, providing information about their health. “You can deduce things,” she says.

Some fintech executives have stated that a more integrated use of customer data could shift their business model. Undeterred by its Valentine’s Day mishap, Revolut is in talks to sell advertising space on its app to brands. Antoine Le Nel, its head of growth, told the FT in April that the fintech could become a true media and advertising business in the future.

In order to sell this to advertisers, the company, which received a UK banking licence over the summer, is looking to increase the time its customers spend browsing its financial app. Like social media companies, it keeps a close eye on its customer “engagement” metric.

Chad West, a former employee of Revolut who led its Valentine’s Day campaign, describes the ad as an “error”.

“Regardless on whether the data was aggregated or fake, it gave the impression that finance firms snoop on your every move and transaction, which is not the case.”

But, he adds, the fintech’s current plan to advertise from within its banking app carries the risk of annoying customers and tarnishing its reputation for a great user experience.

“It’s crucial that they perform solid due diligence on what the short-term impact could be, such as an exodus of privacy conscious customers, versus the long-term impact, such as a loss of trust in the event of a data leak or poor privacy controls.”

Zilch, another UK fintech, has built its business model on this premise. The company, which is backed by eBay and Goldman Sachs and has about 4mn customers, makes money from targeted advertising based on its transaction data which it uses to subsidise the cost of credit for consumers with zero-interest loans.

“We’re actually an ad platform that’s built a credit proposition on top of it,” chief executive Philip Belamant told the FT in June.

For all the enthusiasm, the nascent offerings are yet to prove a game-changer for banks. For Tom Merry, head of banking strategy at Accenture, a consulting firm, their benefits can be overplayed while the challenges are not necessarily worth the potential rewards.

“Banks are sat on tonnes of what I would call ‘nearly useful data’,” he says, referring to “large volumes of aggregated anonymised socio-economic cohort and transaction data” that can become more valuable through enrichment.

“Sometimes people over-emphasise the value of that nearly useful data,” he continues. Banks have it, but also retailers and third party databases as well as loyalty scheme providers. “People can get it from elsewhere, probably as deeply and without having to go into the complex web of integrating with banks.”

Merry says that making substantial money from monetising data would require “scale” and “a sufficiently differentiated set of insights that people would pay a higher margin for it”. Otherwise, he says, “it’s probably not going to change the profile of a bank’s business model”.

Lloyds Banking Group sees the monetisation of its 26mn customers’ financial data as an area of growth. The retail bank launched a “customer insights” team in 2022 that has grown to 40 employees.

Lucy Stoddart, managing director of Lloyds’ global transaction solutions, said one example of this was analysing aggregated and anonymised customer data around shopping habits to provide insights to commercial real estate landlords and help them make better-informed strategic decisions.

The potential for data breaches risks damaging the trust between customers and the institutions holding and managing their money.

A report by consultancy Thinks Insights and Strategy found that people perceive sharing their credit and debit transactions as more risky than other types of data, including health information, because the benefits of doing so are less clear.

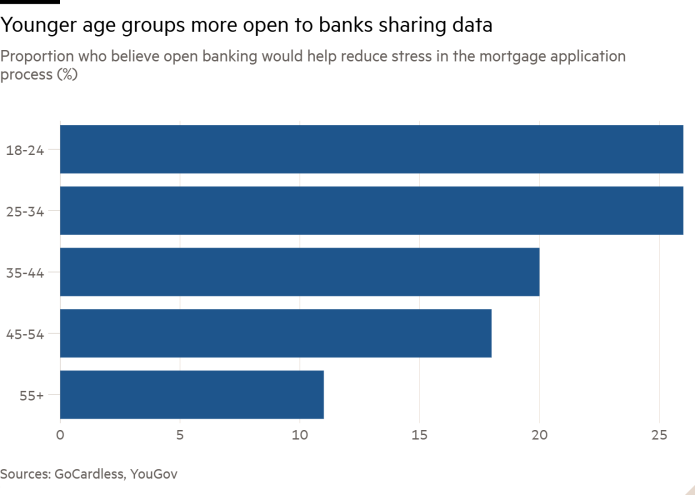

Young people aged between 18 and 24 years tend to worry about data sharing less than their older peers. However, that may be because they have been sharing it their whole lives, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Donna Sharp, a managing director at MediaLink, which helps companies including in financial services to run media campaigns, says analysing customer data is an essential part of the service that banks and payment companies provide.

“The reality is that all these financial institutions have your data; you want them to [have it]. It protects you,” says Sharp. She gives the example of banks figuring out whether a card was stolen via behavioural pattern analysis and geolocation data.

The challenge, she says, is fostering greater “transparency and understanding of how that might be used and what’s the value to you.” She believes consumers are generally fine with their data being used as long as they can see the benefits trickle down to them.

“If [I’m getting] 10 per cent off a trip I want to go on, I’m not mad that you brought that information to me,” says Sharp.

In the UK, the open banking industry, which allows financial companies to access to non-anonymised bank data with the permission of customers, was built on the promise that sharing data in this way would foster greater competition and ultimately benefit customers.

Justin Basini, chief executive of credit report company ClearScore, says data-sharing technology can allow lenders to access information previously only accessible by banks, known as “current account turnover”, in addition to credit reports and scoring. Seeing a fuller picture of prospective borrowers’ financial health allows lenders to adjust their rates and extend credit to more people.

“[As] more data flows, what you end up with over time . . . is much more personal pricing: you get the right price for you based on your credit risk, and you’re not bucketed with other people,” says Basini.

“If the market is basically more able to discriminate risk because there’s more data around, everybody gets a fairer price.”

ClearScore also gives “credit health” scores by using open banking to analyse transaction data to show customers how specific payments such as gambling may affect their options with lenders. Under open banking legislation, ClearScore requires explicit permission from consumers, which has to be renewed every 12 weeks through various loops including ID checks.

Stopping your financial data from being used by your bank or payment provider is tricky. In the UK, any company handling customer data has to comply with a variety of rules. For instance, they need opt-in consent from customers and a legitimate reason to use their data. Claire Edwards, data protection partner at law firm Addleshaw Goddard, says another important principle they need to stick to is “data minimisation” — not collecting more information than is needed.

But this only applies to data that identifies people.

“Once it’s anonymised, it falls outside our regime. The banks are probably already doing whatever they want with that,” she says. “As a consumer you can’t really opt out of that.”

Under UK privacy law, individuals can send “data subject access requests” (DSARs) to ask companies if they are using and storing their personal data, and request copies of this information. Companies have 30 days to respond under the Data Protection Act.

One high-profile case saw politician Nigel Farage send such a request to private bank Coutts after it closed his account. The bank was then obliged to send him a dossier that revealed its reputational risk committee had accused him of “pandering to racists” and being a “disingenuous grifter”.

15%Increase in complaints about data subject access requests in the year to April 2024

Customers dissatisfied with DSARs can also complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office, the UK’s privacy watchdog. Such claims have jumped 15 per cent in the year to the end of April, a freedom of information request sent by consultancy KPMG found. Complaints about financial companies’ responses to DSARs made up the largest share of the total, ahead of the health sector.

This could be because financial companies — and particularly banks built on a patchwork of IT systems — may struggle to source data quickly and present it in a readable way. They also have to leave out information that may breach anti-financial crime regulations. Bank employees are criminally liable for “tipping off” — disclosing information that could prejudice an ongoing or potential law enforcement investigation into a customer’s activities.

Privacy International is campaigning against the UK’s data protection and digital information bill, which would give the government powers to monitor bank accounts to detect red flags for fraud and error in the welfare system.

The campaign group raised alarm around the “extraordinary” scope of these powers. It says they will set a “deeply concerning precedent for generalised, intrusive financial surveillance in the UK” by allowing financial companies to trawl through customer accounts without prior suspicion of fraud.

The group says it is particularly disproportionate that the powers will allow surveillance of state benefit recipients, as well as linked accounts such as those of partners, parents and landlords.

“This wide scope of data collection could create a detailed and intrusive view of the private lives of those affected,” Privacy International said in a letter to former work and pensions secretary Mel Stride.

When it comes to banks analysing their own customer data, advocacy officer Prudencio Ruiz says consent from customers must be “informed” in order to be valid and that they should understand which information might be used, how and to what end. But they also need to be presented with a real alternative.

“You need to be able to say OK, I don’t want to. What’s my option? And if the option is you won’t get the service, then that’s not consent.”