This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s November/December 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

The Denver Museum of Nature & Science is committed to voluntary returns when morally, ethically, or commonsensically justified.

On March 19, 1991, in a short ceremony held at the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, New Mexico, former Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS) curators Joyce Herold and Bob Pickering transferred six Zuni Ahayu:da (war gods) to a delegation of officials, elders, and knowledge keepers from the Pueblo of Zuni, led by Perry Tsadiasi. DMNS repatriated the Ahayu:da for moral and ethical reasons, not legal ones. As The Denver Post editorialized at the time, “it was the right thing to do, by any civilized standard.” That voluntary repatriation, however, occurred within a deeper legislative context.

Four months earlier, on November 16, 1990, US President George H.W. Bush had signed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) into law. NAGPRA created a formal, legal mechanism by which federally recognized Tribal Nations and lineal descendants could request the return of ancestors (i.e., human remains), their belongings (i.e., funerary objects), sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony (i.e., objects owned by a community, not an individual) from universities, museums, and repositories that accept federal funding.

Since that first voluntary return of sacred objects in 1991, DMNS staff have continued to make voluntary returns when moral, ethical, or commonsensical justifications warrant, seeking to move beyond the relatively low bar set by NAGPRA. Two examples—the voluntary reburial of non-Native American human remains in Crestone, Colorado, and the voluntary return of 30 vigango to the Mijikenda tribes of coastal Kenya—provide insight into the historical, philosophical, and ethical contexts for such returns by the museum.

The Repatriation Initiative

In the summer of 2007, DMNS crafted an aspiration statement: “We seek to curate the best understood and most ethically held anthropology collection in North America.” To be the “best understood” meant that we would seek to fill all gaps in our knowledge about the collection—we would address cataloguing backlogs; we would create, maintain, and enhance electronic databases; and we would deliberately work with source and descendant communities to make sure that our knowledge of the collection is culturally accurate and appropriate.

To be the “most ethically held” anthropology collection meant that we would go beyond the specific letter of laws affecting collections; we wanted to proceed with the spirit of those laws firmly in mind. In April 2008, the museum’s board of trustees codified that institutional commitment by formally stating in the Collection Policy that the museum would comply with both the spirit and letter of NAGPRA. That policy also recognized, in writing, that many tribes, communities, and countries might want certain items returned even if there are no formal laws requiring repatriation. In those cases, the Collection Policy recommended that the museum enter “into equal and open communication with the communities that connect themselves to the objects in the Museum’s custody.”

Penning an aspiration statement and getting a policy approved were one thing; doing the work of repatriations and returns was another. Thus, we began a series of projects and programs under the rubric of The Repatriation Initiative to address ethical issues with the collections. The initiative incorporated anthropological understandings of sacred and inalienable property, ethical values surrounding the dead, collaborative methodologies, and notions of restorative justice that allowed us to proactively grapple with the tangled history of DMNS collections.

As we began this work, we came to see repatriations and voluntary returns as a form of social justice necessary for reconciliation between source and descendant communities and museums. In other words, we believe that the museum cannot have a meaningful and productive future with Native American tribes, in particular, until it has resolved its past.

The Crestone Reburial

As we were developing The Repatriation Initiative, we made a conscious decision to no longer curate human remains without informed consent. That decision set in motion a systematic, multiyear process through NAGPRA to repatriate and rebury Native American ancestors. But NAGPRA applies only to human remains that can be identified by archaeological, biological, or other evidence as Native American. What about non–Native American human remains in the collections? It quickly became clear that our informed-consent decision must also apply to non–Native American human remains.

In the fall of 2014, we hosted a daylong interfaith dialogue. DMNS curators and collections staff, all of whom were trained as archaeologists, welcomed Catholic and Unitarian ministers, Buddhist and Hindu practitioners, professors of anatomy and religious studies, and a Cherokee tribal member into dialogue to determine what to do with the non-Native American human remains in our care. (We invited a Jewish rabbi and a Muslim imam to participate; both canceled at the last minute due to scheduling conflicts.)

At the end of a long day, we collectively agreed to rebury the non-Native human remains in a nondenominational ceremony in a natural (no boxes, chemicals, or headstones) cemetery in Crestone, Colorado. That reburial occurred on October 14, 2015.

From a strictly scientific perspective, the loss to science of this voluntary reburial is minimal. There was almost no data associated with these human remains, which represented a minimum of 20 individuals. We barely knew where, when, or how their bones were recovered. From a precedent perspective, we believed that it was time for a major natural history museum to properly care for these people, who never gave permission for their remains to be curated in perpetuity. In this instance, proper care meant giving them a proper burial.

The Vigango Affair

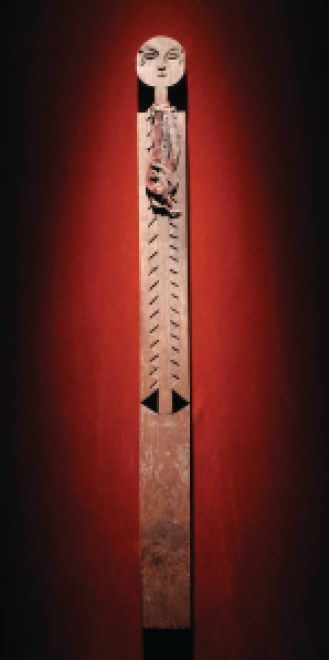

Another example of The Repatriation Initiative in action is the museum’s return of vigango to the Mijikenda in Kenya. In the late 1980s and 1990s, unsuspecting museums across the country unwittingly began to curate people’s souls. These souls came in the form of vigango (singular: kikango), which are wooden funerary posts.

The Mijikenda, literally meaning the nine tribes, have traditional homelands along the coast of Kenya, from Mombasa in the south to just over the border and into Somalia in the north. Two of those nine Mijikenda groups, the Giriama and Kauma, honor deceased relatives who were members of the honorific Gohu society by carving often exquisite, anthropomorphic posts in termite-resistant hardwood. The Mijikenda believe that each kikango embodies the soul of the person for whom it was carved.

Once carved, vigango are erected in local homesteads and in communal, sacred forests; once erected they are meant to decay in place and are not to be disturbed. If they fall over during that decaying process, they are not to be moved. If moved, the groups believe that all manner of spiritual, physical, and economic harm may come to the community.

Unfortunately, in the 1970s through the 1990s, vigango became increasingly attractive to African art dealers and markets in the United States. Vigango were stolen, or purchased under duress, in order to supply that market. In 1990, DMNS accepted 30 vigango donated by a well-known actor and a well-known producer in Hollywood; neither of them had a prior relationship with the DMNS. The vigango were shipped directly from an art gallery in Los Angeles. As far as we can tell, neither donor ever took possession of the vigango, but both took significant tax deductions as a result of their donations. The art gallery made a hefty profit. The Mijikenda, honored members of the Gohu society, and their family members all suffered harm as a result.

In 2009, we recognized that DMNS should not be in the business of curating people’s souls. We therefore started working, slowly but surely, to figure out how to return vigango to the Mijikenda. Over the next decade we made slow progress, but we desperately needed a breakthrough. It finally came in 2018.

That year, I attended the Getty Leadership Institute at Claremont Graduate College in Southern California, and one of my classmates was Dr. Purity Kiura, then Director of Sites, Monuments, and Antiquities for the National Museums of Kenya (NMK). We agreed to work on this important project, and in July 2019, 30 vigango from DMNS arrived at the Fort Jesus Museum in Mombasa, Kenya. NMK is now holding the vigango in trust for the Mijikenda, who hope to build a cultural heritage center closer to their homelands where the vigango can be re-erected and returned to their appropriate cultural context.

Happily, there has been a cascading effect from this repatriation. In July 2023, 37 vigango from the Illinois State Museum and 16 from the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields were shipped to Mombasa as well. We believe more vigango, and therefore Mijikenda ancestors, will be returned to Kenya in the near future.

Once we decided to act, the process for each of these voluntary returns was relatively straightforward, if time consuming. Some of our museum-based colleagues expressed concerns about setting legal precedents, but we turned that concern on its head—what is wrong with setting a precedent by doing the right thing?

As a scientist, I understand that we can, and do, learn wonderful things from the study of human remains. As a museum professional, I understand that museums have done egregious harm to Indigenous communities around the world. As a humanist, I am thrilled to engage in work that is reshaping museum collections with an eye toward new reciprocal relationships with people all over the world.

Definition of Terms

Voluntary repatriation

The return of cultural artifacts, material from nature, human remains, and/or associated data and documentation to individuals and groups representing the culture or country of origin, or to former owners or heirs, when such acts of return are not mandated by law, regulations, or international agreements. The term most commonly refers to returns made to a government entity, rather than a family or individuals.

Restitution

1) The return of cultural artifacts to individuals or heirs of the original owners, as opposed to communities, groups, or countries.

2) Acts taken to restore the situation which existed before a wrongful act was committed. For example, restitution might take the form of restoration of rights, livelihood, land ownership, citizenship, legal standing, or wealth.

Reparations

Compensation for wrongs that cannot be reversed through restitution. This may include direct financial compensation for the cumulative historical effects of damage to a community overall, including to mental and physical health, capital, education, property, and cultural heritage. Reparative practice may also include actions that acknowledge and address harms, and actions or policies that redress systemic economic, educational, or social disadvantages.

Repatriation Principles

The Denver Museum of Nature & Science’s Repatriation Initiative incorporates the following as its guiding principles:

Respect: Honoring people and their things while showing deep consideration for their personal autonomy and collective welfare.

Reciprocity: Creating relationships based on parity and the cooperative exchange of ideas and things.

Dialogue: Committing to open, democratic, and sustained conversation.

Justice: Repairing past wrongs and treating all people fairly.

Resources

Chip Colwell and Stephen E. Nash, “Repatriating Human Remains in the Absence of Consent,”

The SAA Archaeological Record, vol. 15(1), pp. 14–16, 2015

Chip Colwell and Stephen E. Nash, “Why We Repatriate: On the Long Arc Towards Justice at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science,” in Chelsea Meloche, Laure Spake, and Katherine Nichols (eds.) Working with and for Ancestors: Collaboration in the Care and Study of Ancestral Remains, pp. 79–90, 2020

Stephen E. Nash and Chip Colwell, “Reimagining an Ethical Approach to Museum Collections,” in Selma Holo (ed.) Remix: Changing Conversations in Museums of the Americas, pp. 76–80, 2016

Stephen E. Nash and Chip Colwell, “NAGPRA at 30: The Effects of Repatriation,” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 49, pp. 225–239, 2020

Stephen E. Nash, “A Curator’s Search for Justice,” SAPIENS, 2020

sapiens.org/archaeology/vigango-repatriation/

Monica L. Udvardy, Linda L. Giles, and John B. Mitsanze, “The Transatlantic Trade in African Ancestors: Mijikenda Memorial Statues (Vigango) and the Ethics of Collecting and Curating Non-Western Cultural Property,” American Anthropologist, vol. 105(3), pp. 566–580, 2003