What is it that makes a great hero or heroine in children’s literature? The books in our poll feature characters with super strength and magical powers, as well as ordinary children facing extra-ordinary challenges. Is it courage, resilience or a refusal to bow to conventional norms that explains their popularity with voters? And do classic literary heroes and heroines resonate with today’s children in the way that they did with their parents’ generation – those who voted in our May 2023 poll on the greatest children’s books?

More like this:

– The 100 greatest children’s books of all time

– Why adults should read children’s books

– Why is the US banning children’s books?

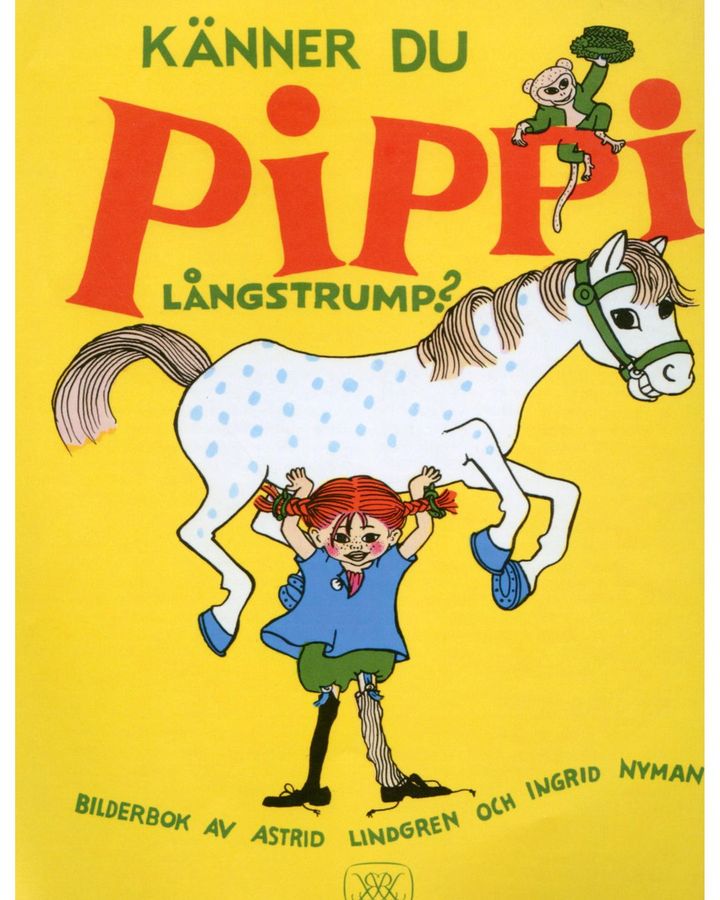

Pippi Longstocking, who burst on to the scene in the 1940s, was herself partly influenced by another iconic heroine – Anne of Green Gables. Both shared red hair and a propensity for telling tall tales. But Pippi was also influenced by Superman. Truly, there had never been a literary heroine like her. Superstrong, she stood up to bullies – and super smart, she frequently bested unreasonable adults. Not only that, but she possessed a suitcase full of gold coins that meant she was financially secure and able to live life freed from the constraints of a conventional childhood. No wonder children around the world did, and do, love her. “She is someone who rebels against the authoritarian norms. She is all about questioning the adult world,” Malin Nauwerck, of The Swedish Institute for Children’s Literature, tells BBC Culture.

Pippi Longstocking is smart, has super-strength, and stands against injustice and unreasonable adults (Credit: Alamy)

Pippi’s character was undoubtedly formed by World War Two, during which she first entered the imagination of her creator Astrid Lindgren – in one scene she hilariously gets the better of a circus strongman called Adolf – but she was also the product of changing views around childhood. In 1900, the Swedish philosopher, Ellen Key, had published a highly influential book, The Century of the Child, in which she predicted that the 20th Century would be a period of progressive thinking around children’s rights. Lindgren took “the idea that children were becoming more competent and empowered and increasingly seen as individuals in themselves, and packaged it in a very understandable way,” says Nauwerck. “Pippi has been called the child of the century in response to those ideas.”

But if she was a child of the 20th Century, what explains her enduring popularity in the 21st? “She is almost a mythical trope – David against Goliath. She represents the underdog, the children, against the stronger oppressor, the adults. She has these symbolic qualities that make her very recyclable,” says Nauwerck.

“The contemporary reading of the Pippi symbol has come to be a lot about strong girls and how Pippi is a role model for girls,” says Nauwerck. It is perhaps unsurprising that Greta Thunberg, another young Swedish girl who challenged adult authority and built a global movement in the process, has been portrayed as Pippi.

Pippi is aimed at the under 10s, who appreciate the often slapstick humour within the tales – silliness is perhaps an underappreciated quality of children’s literary heroes and heroines – but older children, unsurprisingly, need characters that reflect their own lives and concerns.

At the TioTretton library in Stockholm, which caters for 10 to 13-year-olds, no parents or carers are allowed inside, which means that children are free from their influence and able to read and talk about the things that really matter to them.

“Right now we see an increased anxiety about the future from our kids at the library. There is a great worry about the environment, will there still be a planet for them when they grow up?” says library co-ordinator, Amanda Stenberg.

This age group is also coming to terms with “the fact that grownups are not always right or wise or make good decisions, and that is something you have to deal with because they still have authority over you even though they’re not right,” says Stenberg.

Calm, funny Charlotte and brave pig Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web both have heroic qualities (Credit: Alamy)

Unsurprisingly this influences the kind of books they want to read. “All the books that are popular in some ways have a conflict whether it’s against society, or adults, or among friends or in a school,” says Stenberg. “And then there is the brave act of standing up to it,” she adds. The children want to see “characters who are not afraid to speak up about injustices, and who have the courage to defend the rights of others.”

This of course includes characters such as Anne of Green Gables and Matilda, but Stenberg believes that these classic books “should be complemented by newer books which more accurately can address the topics of today”.

She says that few of the books in the poll would be chosen by the children themselves. Something that Louis Lareau, managing librarian at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library Children’s Center in New York, agrees with. “Kids (and parents) are now actively looking for characters that reflect themselves – their culture, heritage, language or physical appearance,” she tells BBC Culture.

According to Marie Moser, owner of The Edinburgh Bookshop in the Edinburgh suburb of Bruntsfield, classic titles are bought by parents or grandparents, who fondly remember the reading experiences of their own childhood. Which is not to say that children don’t still enjoy them. However, when left to their own devices, children will pick books that contain characters they themselves can connect with or identify with, although this doesn’t necessarily mean they will have to be in a contemporary setting.

“Some of them want to see kids like themselves because that’s how they roll, some of them want fantasy because they find real life too scary,” Moser tells BBC Culture.

Universal appeal

Harry Potter seems to be popular with both of these camps. “It’s about the downtrodden rising up, which is a classic theme, and people behaving decently despite the people around you, the adults, not behaving decently,” says Moser when explaining the series’ universal appeal.

Both Harry and Hermione in the Harry Potter series have gained a following for their courage and decency (Credit: Alamy)

Moser’s shop holds regular Harry Potter events where she always finds it intriguing to find who dresses up as who. For the 20th anniversary party “we had a lot of Harrys, because he’s the hero, but we had a shedload of Hermiones. Boy, do little girls love Hermione! Because she’s smart and she’s not girly girly, and I think they see themselves in her. Hermione is incredibly empowering for a lot of little girls,” she says. Matilda is another perennially popular heroine. “I think children always like underdogs getting their own back. There is a joy about Matilda. And she’s smart, like Hermione,” says Moser.

Kelly Hurt, editorial director of children’s books publisher Puffin, agrees that “children often feel very strongly about an underdog – characters that have to face up to problems with strength, humour or talent. There’s something about the vulnerability of a lot of classic and modern characters – Tracy Beaker, Harry Potter, Lyra Belacqua, Greg Heffley – that makes you root for them,” she says.

Mosser believes that the lack of accountable adults in Matilda’s life also makes children engage with her. Indeed, many of the most popular children’s heroes and heroines share this trope – either they have uncaring or absent parents, or they are orphans. “There’s no direct parent, almost implying that their love is conditional on you being the person they want you to be. There’s always someone disapproving and that’s much easier to deal with.”

In Mosser’s view, Tracy Beaker author Jacqueline Wilson is the biggest author missing from the poll. “She’s adopted by the children who don’t want that magical end to a story because their lives have been difficult. One of the reasons she started writing is that Matilda is the fantasy version of that life, and yet she knew people who really were growing up in tough homes and she felt that wasn’t in books.”

It would be nice to think that there is room on the bookshelves of today’s children for both classic and contemporary titles, offering a voyage of discovery for both parent and child.

“Books are a safe place for children to explore ideas and think about how they would respond to dangerous or exciting situations – and through classic characters they can live out all sorts of potential lives,” says Hurt. As a child her favourite hero and heroine were Wilbur and Charlotte from Charlotte’s Web. “I loved Wilbur’s bravery and determination and Charlotte’s calm humour,” she says.

Those are characteristics that are still present in today’s heroes and heroines. Children are always going to love the plucky underdog. Someone who is a little unconventional but still kind, compassionate and unafraid to stand up to oppressors, whether that be the school bully or unreasonable adults. As Moser puts it: “I think in some ways that hasn’t changed. It’s just the stories they’re doing it in.”

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest children’s books:

–The 100 greatest children’s books

–Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

– The 20 greatest children’s books

– The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

– Who voted?

#100GreatestChildrensBooks

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.