On the morning of 8 December, along with millions of Syrians, I awoke to a country no longer governed by the iron fist of the regime that had ruled for 54 years.

I am Syrian but I no longer live in Syria. I am now a science journalist on staff at Nature and living in London.

It is hard to put into words what so many of us Syrians are feeling. There is shock, as the fall of the former president Bashar al-Assad happened at unprecedented pace.

We never imagined the scenes of statues being toppled all across Syria, both of Assad, or his father, also a former president, Hafez Al-Assad. Nor did we foresee that thousands of political prisoners, people who had spent decades being incarcerated, tortured, their eyes barely opening, would stagger into the daylight.

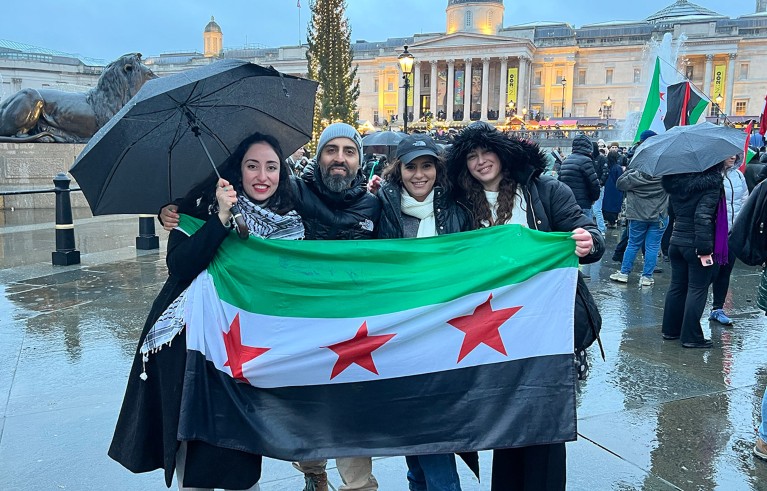

I moved to the UK in 2013, after the city where I was born and raised, Homs, was bombed out of recognition. I have never seen London’s Syrian community so joyful, as yesterday when we gathered in Trafalgar Square, waving flags, dancing and singing songs of liberation.

Left to right: Miryam Naddaf, Thaaer Ganede, Nisrin Kakhya and Maya Alestwani. Trafalgar Square, London, 8 December 2024.Credit: Thaaer Ganede

For Syria’s scientists there is a mountain of work to be done.

For the first time, the world has seen the insides of Assad’s slaughterhouses and terrifying prison cells, the places of torture where so many lost their lives, not only Syrians but people of Lebanese and Palestinian origin.

There are blood stains everywhere. There is one known mass grave in a Damascus suburb and more might be found.

Forensic scientists will be needed to identify the deceased and the survivors, too. Geospatial analysis will be needed to locate sites used as prisons, as well as the places where people are buried, all of which will need to be designated as crime scenes. It is well known that the Assads used chemical weapons on their own people; stockpiles of these weapons will have to be first found and then destroyed. All forensic evidence will need to be preserved, so that, ultimately, justice can be delivered.

Then there is the monumental task of rebuilding Syria’s universities and research institutions. Things worsened after the Arab Revolutions of 2011 when, briefly, young and old, came out onto the streets demanding freedoms. In response, the regime bombed schools and universities. My own primary school was used as a burial site.

There is a large community of Syrian scientists living and working abroad. Many have strong connections with the international research community and will be needed to help revitalize scientific education, research and infrastructure.

It is impossible to overstate the feeling of freedom. For more than half a century, Syria’s people, including its scientists and its university students and faculty did not know what it is like to not be constantly monitored by Assad’s hated and feared secret police.

The most important examination that any student needed to pass was a test of loyalty to the regime – nothing else mattered. If you failed, it was prison, torture or exile.

The fall of the Assad regime is the end of an era. It is also the beginning of hope, but it is hope that lies at the end of a long and challenging road, territory that is new for Syrians.

People have suffered unimaginable losses. With the regime gone, Syria will hopefully have the opportunity to rebuild its scientific community and restore intellectual freedom. The country’s educational and scientific community, shattered by war, has a chance to be reborn. It will need all the external help it can get.